The National Horseracing Museum in Newmarket, Suffolk unexpectedly revealed some interesting material texts when I visited recently. Newmarket is famous as a horseracing town, but it is particularly important in the racing world not so much for its racecourse (a feature of over fifty towns and cities in the UK) but for its training ground, the Heath, a grass-covered chalk incline just outside the town which has remained unchanged since it was first used to train racehorses in the late seventeenth century.

Horseracing has taken place in Britain since Roman times. The breeding of fine horses has long been associated with royalty, but it was not until the later seventeenth century that horseracing as we know it today became central to the British sporting scene. I had (perhaps naively) expected the museum to explain more than it did about the social history of horseracing as an essential part of the life of Newmarket and many other racing towns. Instead, the museum feels more like a shrine to the equine form, which is probably a better reflection of a sport concerned not just with the competitive racing of horses, but ultimately with the complex art of creating the finest possible equine physique. This obsession with the body of the horse is extended by association to the bodies of jockeys; among the many artefacts linked to jockeys that were afforded a relic-like status in the museum’s velvet-lined glass cases, the most macabre was the pistol with which the famous local jockey Frederick Archer fatally shot himself in 1886 at the age of 29.

While displays of stuffed horse heads, preserved horse feet, and equine enema equipment are all of limited appeal to the non-specialist, the museum is more interesting for the rich tradition of material texts associated with horseracing it reveals. There are some lovely examples of race cards, race tickets, and betting slips from the last few centuries, which provide a glimpse into the particular social and cultural context of this sport. The most significant material texts associated with horseracing, however, are the incredibly complicated graphs and diagrams of ‘sire lines’, essential reading material for any true connoisseur. These texts are the very foundation of this sport, enabling the precise genetic origins of individual horses to be traced back across hundreds of years. Sire lines have a revered status, informing the decisions of breeders, owners, trainers, bookmakers, and the many other people integral to this sport.

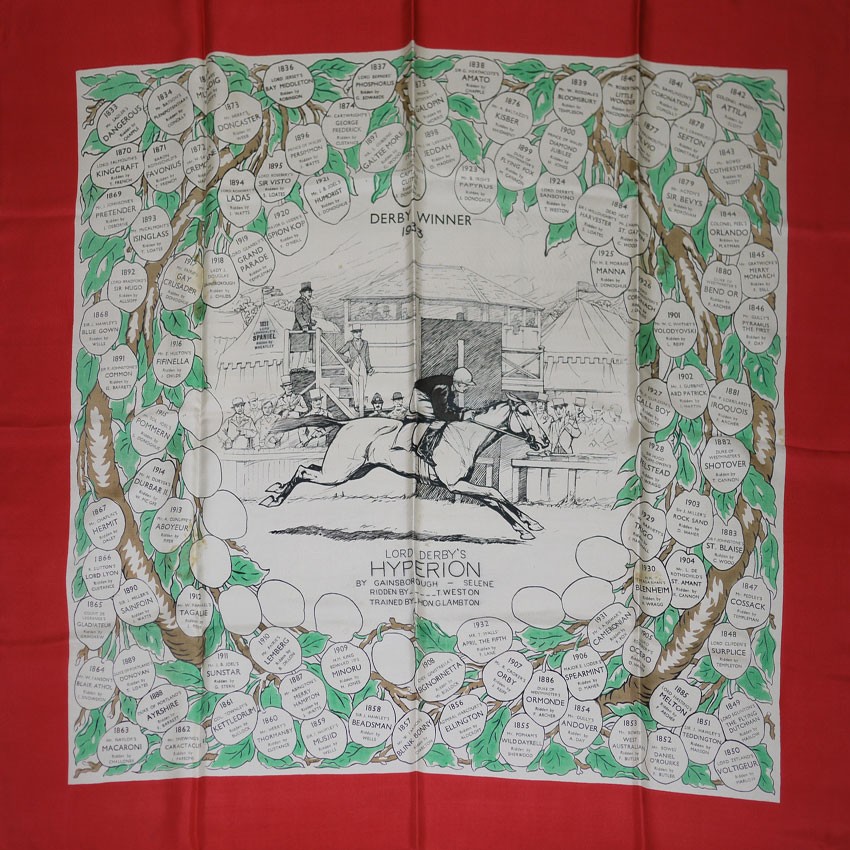

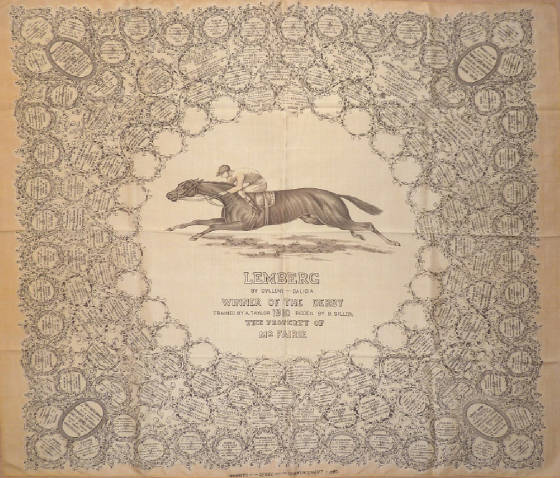

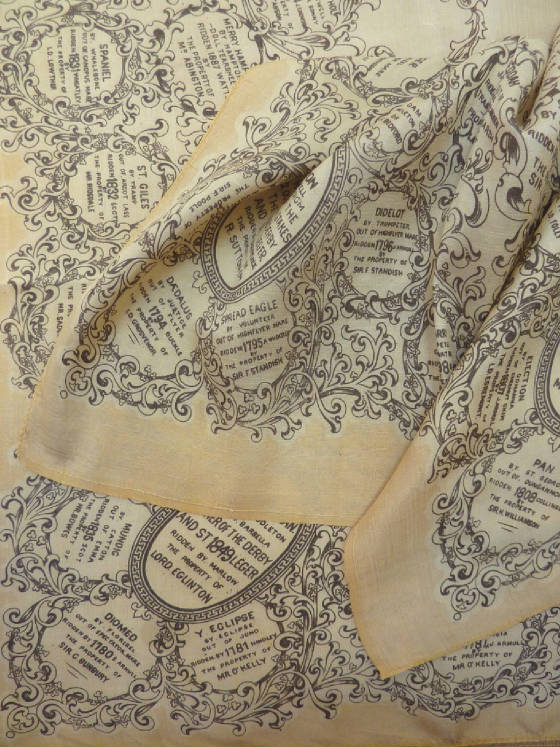

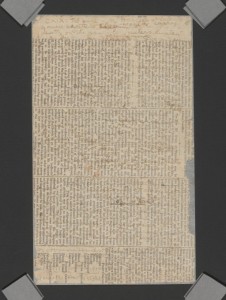

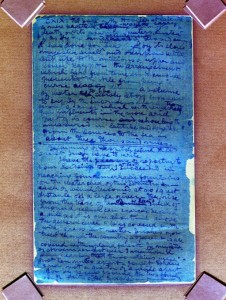

The pictures above show Derby silk scarves, which throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were produced annually in connection with the Epsom Derby, one of the most famous horse races. Printed with the name of the year’s winner, they also feature an elaborate collage of the names of all previous winners since the inauguration of the Derby in 1780, along with the details of each individual horse’s parentage. These souvenirs exploit the iconic status of sire lines and the very poetic language of horse naming, turning intricate textual charts and diagrams into a highly aesthetic object.