I work with manuscript and printed material dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These texts often have complicated material histories, especially in those early, hectic days, weeks, months, and sometimes years during which they were created, read, annotated, copied, and then placed somewhere for safe keeping – or, perhaps, passed on to a new owner who read, annotated, and copied them all over again. From time to time I have edited materials like these for scholarly publication, and during the course of research I have generated an enormous amount of data about them, most of which now exists (if it exists) in scribbled forms on scraps of paper. When someone comes along in thirty years and wants to re-assess manuscript and printed materials, that scholar will need to repeat the entire process of discovery that led to my original conclusions, before (very likely) she surpasses them to form her own, better ideas. Wouldn’t it be nice, I often think, if we could find a way to create durable records of our research in real time? If we could generate not only scholarly editions, but research spaces in which users could follow us on our journey from the first encounter with, say, a 1581 manuscript letter, all the way to our final judgments about the nature of that letter’s contents, its relationship to other extant letters, the history of its circulation, and so on?

This sort of technology is probably a long way off, though I think I can see how it might work. An observing computer would follow our train of thought, possibly by logging it at key nodes (much as you might tag essential features in an electronic image you are manipulating onscreen), and then display in some intuitive interface a map or narrative that linked those nodal points together in a history, drawing on three-dimensional video, audio, and other kinds of sensory recording. A user could ‘read’ – or experience – a transcript of the process of my research. Don’t worry: they’ll have medication to cope with the outcome.

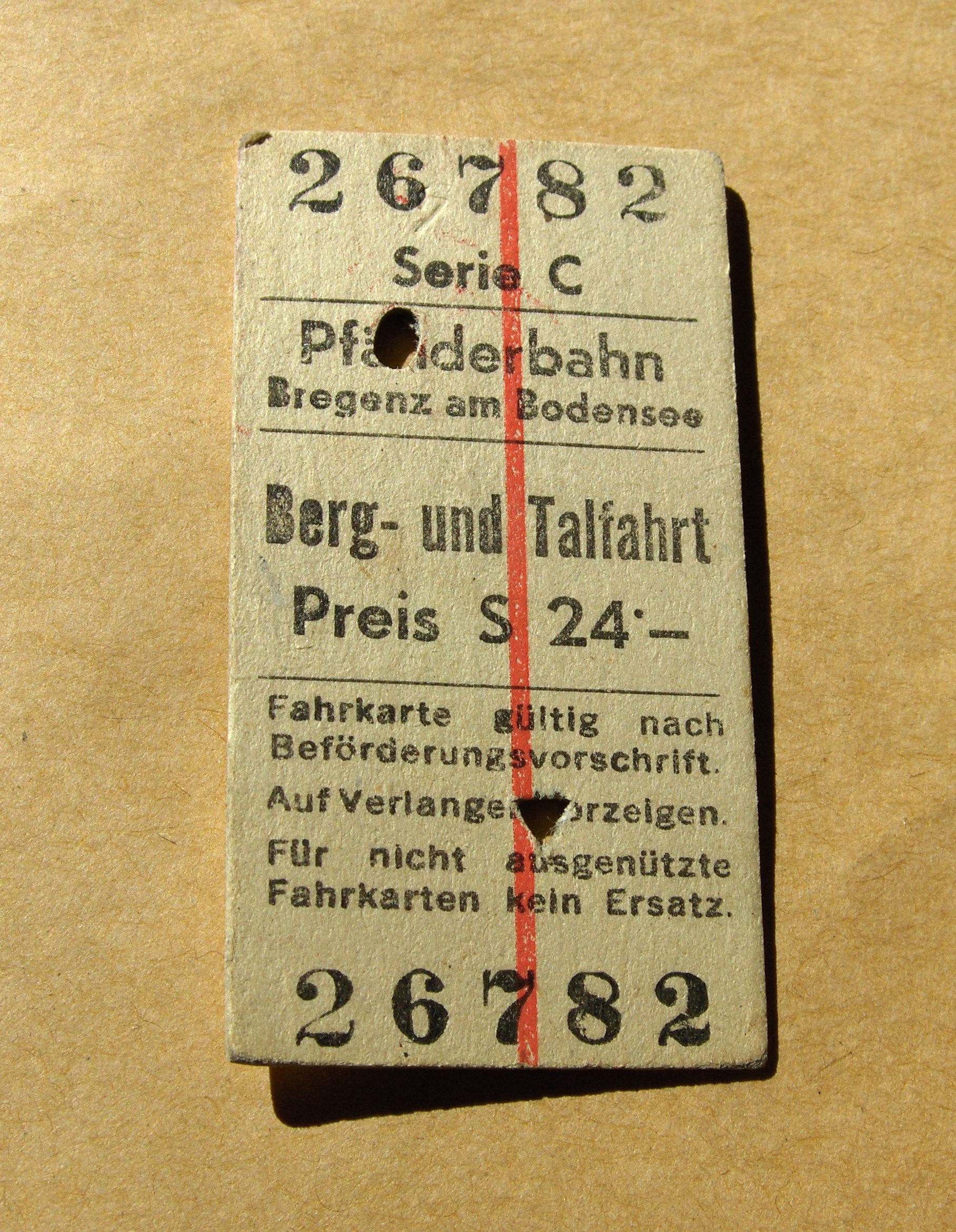

But we’re not there yet. In the meantime, we have Tales of things, a new service launched by the TOTeM project (a collaboration between Brunel University, Edinburgh College of Art, University College London, University of Dundee and the University of Salford, funded by the Digital Economy Research Councils UK), at http://www.talesofthings.com. Tales of things is conceptually a simple venture, but one that may have huge consequences. The website encourages you to start tagging the physical objects around you (that is, in the real, material world) with scannable tags – probably printed onto a sticker – each showing a unique identifer. This identifier will permanently link the physical object to a web page, where you can tell the tale of that thing: record its history, your history with it, or whatever you fancy. If someone else encounters the thing, and scans the code with their mobile phone or other device, they can then log onto the website and read your comments, and the comments of anyone else who has encountered and written about that thing, using its unique identifier. We’re now used to attaching metadata to electronic objects. Make no mistake: metadata just got a whole lot weirder.

Tales of things may seem to offer an alternative to the material text, inasmuch as it allows us to create textualized materials. But it offers an exciting glimpse of what may be the future of manuscript study, or bibliographical research on old printed materials, for people like me. If we could put an electronically scannable tag on a British Library manuscript – or, if you’re glue-shy, just tuck it into the mylar sleeve that will (budget constraints permitting) one day hold and protect that manuscript page – we could link the physical object to a store of metadata to which everyone in the world could have instant, unfettered access, all the time. After a day in the National Archives looking at Spenser’s letters, I could load every single byte of my typed notes onto a central server, carefully disposed by object, at the expense of only a very little labour – probably as little as a few clicks.

Once the data was on a server – and remember, everyone’s data would be on the same server – we could start thinking about how to solve problems like longevity, file format security, and of course cross-referencing. It’s a lot easier to conserve and migrate data when it’s all homogenous. And it would be trivial (for someone) to write a piece of software that would spider the manuscript data pages, looking for cross-references to other manuscript data pages, and then link them in trees and networks that would help us to understand the relationships between the material texts themselves. Best of all, though, this data would continue to be available in a wiki-like space for other researchers to access, modify, and enhance, potentially forever.

The Tales of things project gives us a tiny peek at what a decentralized library cataloguing environment could look like – or perhaps it would be better to call it a hyper-centralized cataloguing environment, one in which all library collections could be virtually federated, and the historical connections between their associated (but till now sundered) items and collections mapped, and in some sense restored. It allows us to see how the knowledge-moments of individual researchers could, through tagging, join the corpus of scholarly publication and become part of the enduring scholarly record – but a record that could evolve more organically than authored publications will ever allow.