The latest issue of the Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society has an entertaining article by Liam Sims on the formation of the ‘Arc’ classification in the Cambridge University Library. ‘Arc’ is short for ‘Arcana’, and this is CUL’s equivalent of the British Library’s ‘Private Case’ or the Bodleian’s Φ [Phi] classmark — the latter apparently a clever-clever pun on the English word ‘Fie!’ This is, in short, the rude stuff — banned books; sexual psychology and physiology; books of nudes.

Sims describes how hard it is to work out where the ‘Arc’ shelfmark came from, or how anyone knew it was there–the problem books were already being grouped together in the 1880s but it wasn’t until the 1910s that readers were told about them. He also shows that Oxford and Cambridge librarians were privately sharing notes about their handling of obscene materials in letters of the late 1930s. Stephen Wright at Oxford wrote that Φ books were only given out freely to those ‘whose moral character we consider sufficiently irreproachable’, whilst ‘undergraduates and doubtful applicants’ needed to provide ‘convincing evidence of their good faith’. H. C. Stanford at Cambridge–where books were usually borrowable–said that volumes of nudes (drawn or photographed) couldn’t be lent out, as they tend ‘to return adorned … with phallic additions’. Stanford added a handwritten postscript to one of his letters, noting that the Bodleian had Lady Chatterley, but CUL didn’t; ‘but I happen to have a copy of the first edition which will, I suppose, ultimately find a home here’.

Swollen with gifts of erotica from A. E. Housman and Stephen Gaselee, a former Pepys Librarian, along with libellous books and with ‘cancelled’ misprinted books (which live a kind of shadow life, since they can never be brought out for readers), the Arc category now contains around 1200 volumes. Sims suggests that the books that were hidden away from public view may have been much consulted by ‘attractive young men’ among the librarians, some of whom went on to write Arc books themselves. He gives us a picture of one such librarian in his jacket and tie, so that we can see just how attractive he was. This is a comparatively mild form of erotica, given what the article might have offered.

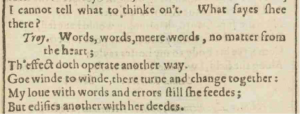

There are a few moments in Shakespeare that capture these aspects of paper. Amid the utter bleakness of the ending of Troilus and Cressida, Troilus receives a letter from Cressida. We never find out what it says; Troilus dismisses the contents as ‘words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart’, before tearing it up. ‘Goe wind to wind, there turn and change together’. The fluttering of the paper becomes a visual metaphor for what Troilus perceives to be his beloved’s faithlessness.

There are a few moments in Shakespeare that capture these aspects of paper. Amid the utter bleakness of the ending of Troilus and Cressida, Troilus receives a letter from Cressida. We never find out what it says; Troilus dismisses the contents as ‘words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart’, before tearing it up. ‘Goe wind to wind, there turn and change together’. The fluttering of the paper becomes a visual metaphor for what Troilus perceives to be his beloved’s faithlessness.

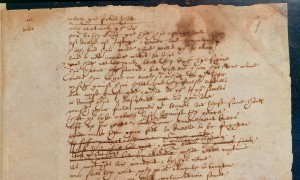

n image from the manuscript of Christina Rossetti’s ‘Sing Song’, the subject of Mina Gorji’s paper at the History of Material Texts seminar on Thursday. It’s an anthology of nursery rhymes, charming and faintly macabre in equal measure, as in this ceremonious poem for a dead thrush, and illustrated in faint pencil-sketches by the author. You can view the whole book

n image from the manuscript of Christina Rossetti’s ‘Sing Song’, the subject of Mina Gorji’s paper at the History of Material Texts seminar on Thursday. It’s an anthology of nursery rhymes, charming and faintly macabre in equal measure, as in this ceremonious poem for a dead thrush, and illustrated in faint pencil-sketches by the author. You can view the whole book