To live in the modern world is to be a slave to form-filling. Our births and deaths require official certification, and in the interim we receive regular reminders that we are merely a number in an endless sequence of numbers. The documents and papers that assert our identity render us anonymous, reminding us of the terms of a mass society in which we are interchangeable and insignificant.

Simon Franklin’s paper at the History of Material Texts seminar last night traced the prehistory of bureaucracy by surveying the development of printed blank forms in Russia. Printed forms have become increasingly interesting to historians of the book in recent years, largely as a way of questioning the centrality of ‘the book’ in print culture. Single-sheet blanks were produced in large numbers from the very inception of print in the West, and they played an important part in making print commercially viable–no printing house could have made a living out of the works of Aristotle.

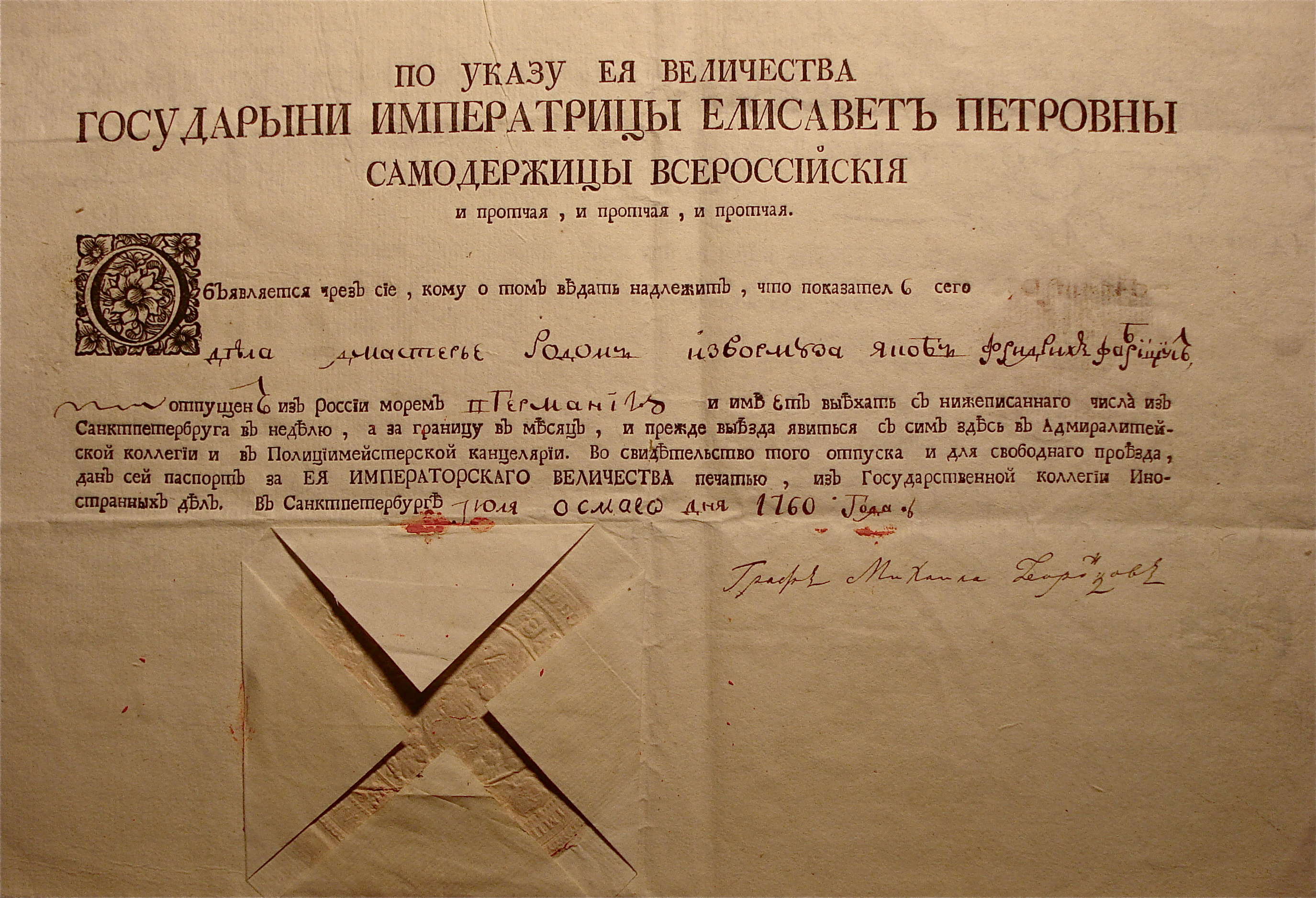

Looking at Russian forms complicates this story, however, since Russia was one of the many places where printing completely failed to enter into an alliance with market capitalism. The idea of ‘the printing press as an agent of change’ (to use Elizabeth Eisenstein’s celebrated formulation) becomes problematic in relation to a culture in which printing remained a state monopoly and where almost the only printed books were religious titles intended for use in church. Franklin’s research in Saint Petersburg has yielded a fine haul of forms of all kinds–passports, travel permits, grants of land and title–and has suggested that there was a decisive turn to print in the early eighteenth century, probably thanks to the Europeanizing project of Peter the Great. Even after this (comparatively late) move, there were frequent failures in the distribution of forms, so that people continued to produce manuscript copies with the attendant risks of forgery and malpractice. It takes a lot of effort to create a bureaucracy.

It’s easy to get absorbed in the material features of the forms themselves–the combination of printed text, decoration, handwritten names and numbers, stamps and seals… They are fascinating, I suppose, because the bureaucratic bustle, the proliferation of elements and agents, aspires to a finally unattainable ideal, a fantasy of authentication. In this sense the blank form seems to epitomise the anxieties about truth and lying that have always dogged the printed word.