‘You wouldn’t want to appear at a fashionable party with a book that looked like this…’ This insight into Victorian etiquette was offered today in a talk given by Jim Secord (historian of science and a member of the CMT’s advisory committee) at the Cambridge ‘Things’ seminar. Secord’s aim was to consider the relationship between the physical presentation of books and the reading experience in the nineteenth century. Of particular interest was the development of the publisher’s cloth binding in the period, and how this related to the rise of a middle-class reading public that wanted quality and durability without the need for personalised rebinding. By thinking about the cloth of books in relation to fashionable clothing, Secord hoped to ‘get back to the reading experience and what it actually meant’ at a time when new technologies were transforming the business of making books.

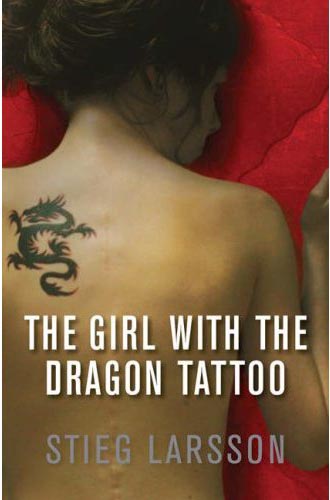

Following Secord, Kristina Lundblad‘s paper began by demonstrating how much we do in fact judge a book by its cover, and how much we now rely on the fact that books are differentiated by their covers. She displayed a striking slide showing what happens when you put the words ‘Pippi Longstocking/Astrid Lindgren’ or ‘The Gift of Death/Jacques Derrida’ on a particular illustrated front-cover, in place of the original words ‘The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo/Stieg Larsson’. Pan back in time to the early nineteenth-century and the physical forms of books were mostly very anonymous. Since their bindings were often paid for by the consumer, there was no need for them to advertise the book’s contents or to catch the eye. Only when publishers started to take over the job of binding did this situation begin to change. In England, titles appeared on covers from the 1840s; by the 1850s custom-made images might be embossed along with the author’s name and the title. By the end of the century, the covers of the book were a design space to be filled with all manner of colourful images, and each book was an individualised thing–all thanks to the marvels of mass-production.