One of the stranger consequences of the coronavirus lockdown has been a growing fascination with the contents of the bookshelves that are suddenly visible in the backgrounds of politicians and pundits forced to Skype or Zoom or Facetime in to deliver their wisdom to the nation. Such bookshelves have long been a matter of passing interest for the way that they help to shore up the authority of the speaker, and for the occasional revelations they offer about the intellectual coordinates of a politician’s life. But now they have become unavoidable.

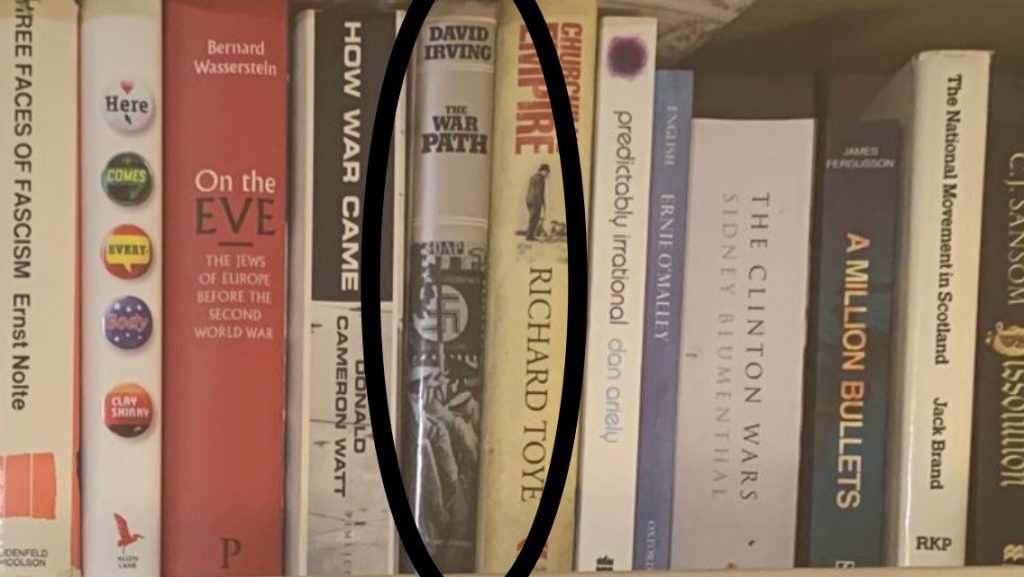

Yesterday we were briefly transfixed by the “shelfies” of the conservative politician Michael Gove and the Daily Mail commentator Sarah Vine, in which the eagle-eyed spotted copies of The War Path, by the Holocaust denier David Irving; Herrnstein and Murray’s The Bell Curve, which argues that intelligence is unequally distributed by race; and Ayn Rand’s right-wing novel Atlas Shrugged. Many commentators noted that owning a book doesn’t mean that you agree with its contents, while others remarked on the general lack of female writers among Gove’s heavyweights, or wondered what the response would have been had Jeremy Corbyn (repeatedly accused of antisemitism during his time as leader of the Labour party) been found to have holocaust deniers on his shelves. Last night, BBC’s Newsnight ran a feature in which they showed politicians in front of their bookshelves, and gender was again at issue: we’re sorry for the preponderance of men, Emily Maitliss told us, but that was because it’s men who tend to sit in front of bookshelves for their interviews. And a Twitter account called ‘Bookcase Credibility’, which circulates pictures of egregious shelf-parading, is trending.

All of this was of course just the usual storm in a social media teacup, which will soon blow over and leave us exactly where we were before. But it has a particular resonance for those of us who work on the history of libraries, or for people like me who just find themselves unable to take their eyes off other people’s bookshelves. My recent book, Shakespeare’s First Reader, grew out of the fits of nosiness that sweep over me when I visit a friend’s house and see their shelves, tranposed to the sixteenth century. What are all these books? Where did they come from? Have they been read? How have they shaped the life, the experience, the identity of the person I thought I knew?

Part of the fascination is, of course, not just in the individual items but also in their disposition—neatly organised or heaped-up and messy? well thumbed or pristine?—and the relationship between the books and the rest of the room, with its multiple markers of taste, wealth and interest. The material details are so telling, though often in ways that are hard to formulate: we just react to them with a shiver or a feeling of warmth. But beyond that, the sight of a bookshelf sets up an oscillation: it lets you in and screens you out; holds out the books but keeps them firmly closed; shows you ‘reading’ whilst asserting that you could never see something as intimate and secretive as reading. All of this explains why I’ll be keeping more than half an eye, with a twinge of guilt, on that twitterstorm.