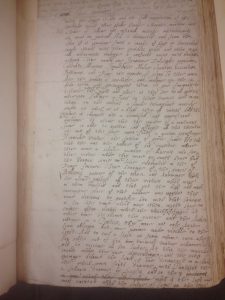

A new exhibition opens at Cambridge University Library today. ‘Discarded History: The Genizah of Medieval Cairo’ puts on show just a few of the 200,000 manuscripts found in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo in the late nineteenth-century. These were books and documents of all kinds that were no longer needed, but which could not be destroyed because they bore the holy name of God.

A new exhibition opens at Cambridge University Library today. ‘Discarded History: The Genizah of Medieval Cairo’ puts on show just a few of the 200,000 manuscripts found in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo in the late nineteenth-century. These were books and documents of all kinds that were no longer needed, but which could not be destroyed because they bore the holy name of God.

Conserving these fragments, many of which were ‘literally ground to dust’ in the crush of a single chamber (the Genizah) of the Synagogue, has been a major effort for the library in recent decades. Making sense of such an enormous and multifarious collection has proved just as difficult. Launching the exhibition, Ben Outhwaite said that the curators could have tried to dazzle spectators with ‘the first x’ and ‘the most important y’, but instead they went for a subtler approach, showing how this treasure haul of documents sheds light on the richly multicultural life of an ancient city.

The variety of materials is extraordinary: good-luck charms, prenuptial agreements, alphabet primers, first-hand accounts of earthquakes, and numerous letters–from a refugee, a woman with leprosy, the head of the Jerusalem Academy. There is Moses Maimonides’ treatise on aphrodisiacs (‘if ox-tongue is placed in wine until its strength is extracted, it greatly increases the joy and strengthens sexual intercourse’). There’s a trousseau list including ‘a pen-box made in China’ and a lavish collection of robes and wimples. And there’s one letter in which a woman threatens to go on a hunger strike (in the daytime, at least) if her husband doesn’t come back home full-time, rather than only turning up on the Sabbath. He writes on the back: ‘If you don’t break your fast, I won’t come back Sabbaths or any other day!’ In its charming and its less-than-charming details, it’s an absorbing display.