Throughout the process of scholarly research, tangents seem to reveal themselves all the time. They quickly tempt you away from your original point of focus and offer the possibility of a story entirely different from the one you were looking for. When I came across a set of annotations in a Cambridge University Library copy of Henry Billingsley’s 1570 edition of Euclid’s Elements, I was confronted with one such tangent, which I felt compelled not to ignore.

A ‘pop-up’ from Billingsley’s edition of Euclid; CUL Adams 4.57.1. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

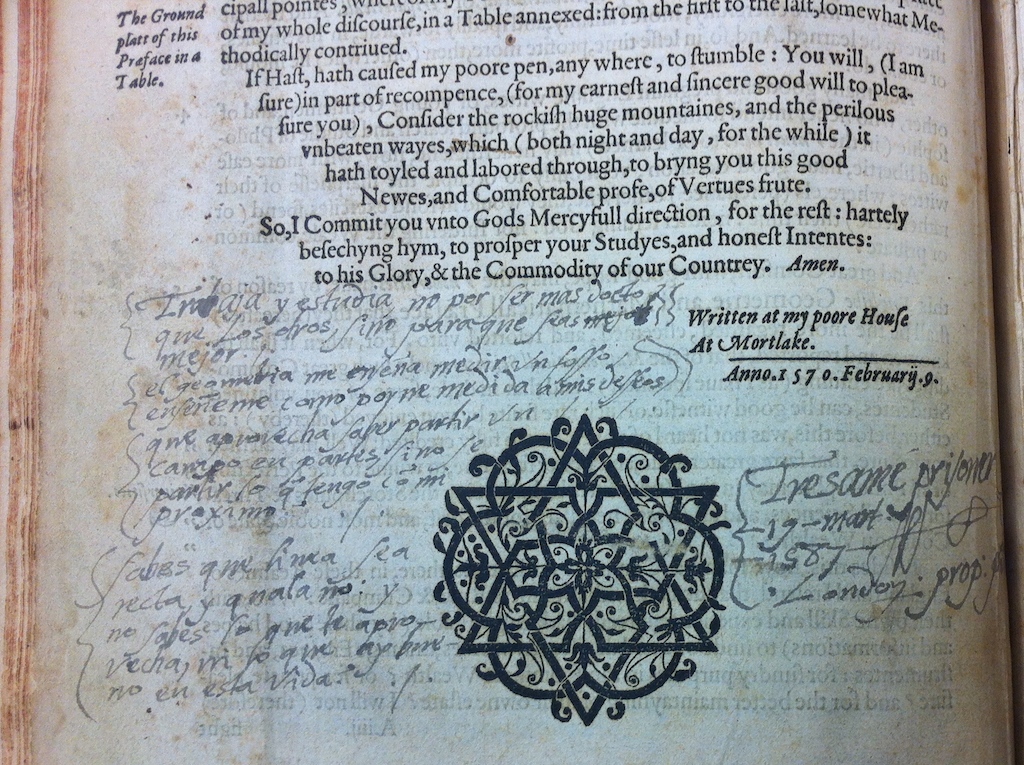

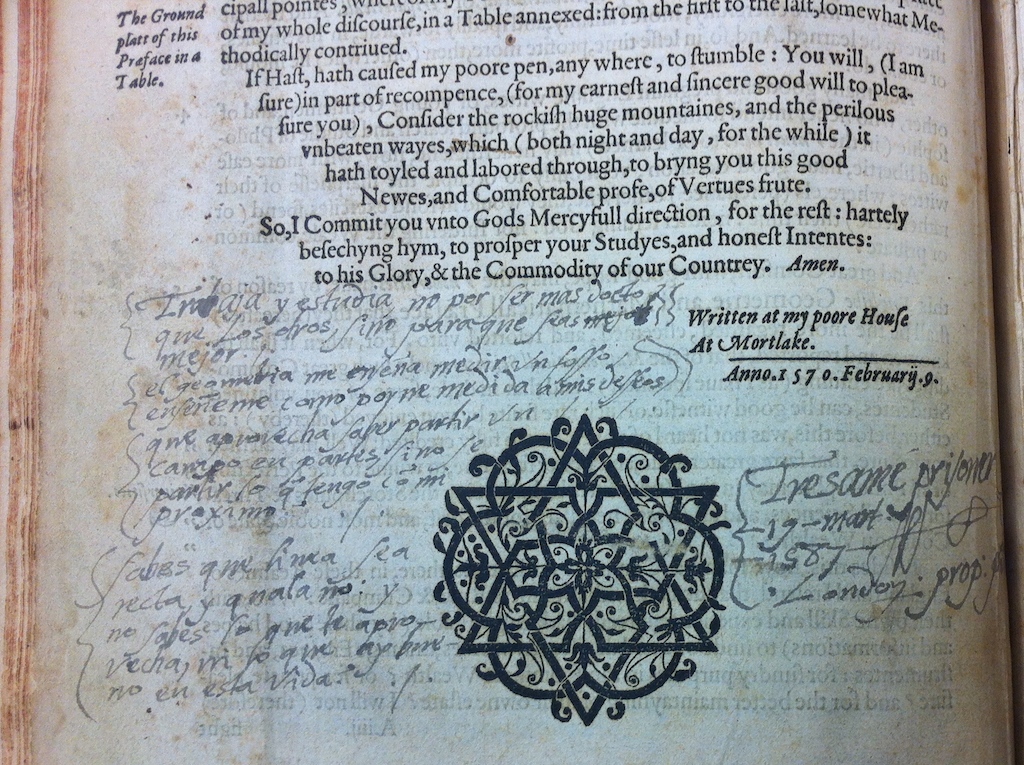

I was looking at the book as part of the early stages of my PhD research on the intersections between early modern mathematical thinking and the period’s drama. I felt that to truly understand the intellectual history I was interested in, I needed to learn its content myself, and to put myself through the kind of education an aspiring mathematician in Elizabethan England might have had. I decided to do a quick survey of every mathematical book held in the Munby rare books room, so long as it was printed in London between 1500 and 1650. By far the most beautiful and ambitious of these books was Billingsley’s: a massive volume printed at great cost and featuring what might be England’s first ‘pop-ups’. I quickly found unusual handwritten annotations: three sentences placed at the beginning of the volume’s lengthy preface by John Dee and another three at the end. Their mixture of Spanish and Latin at first made them opaque, but the signature underneath the first set of annotations captivated me: ‘Tresame prisoner’. These were the writings of a criminal.

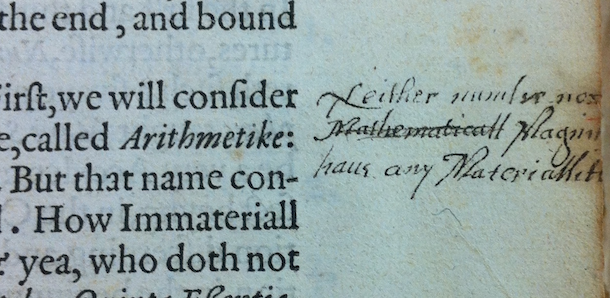

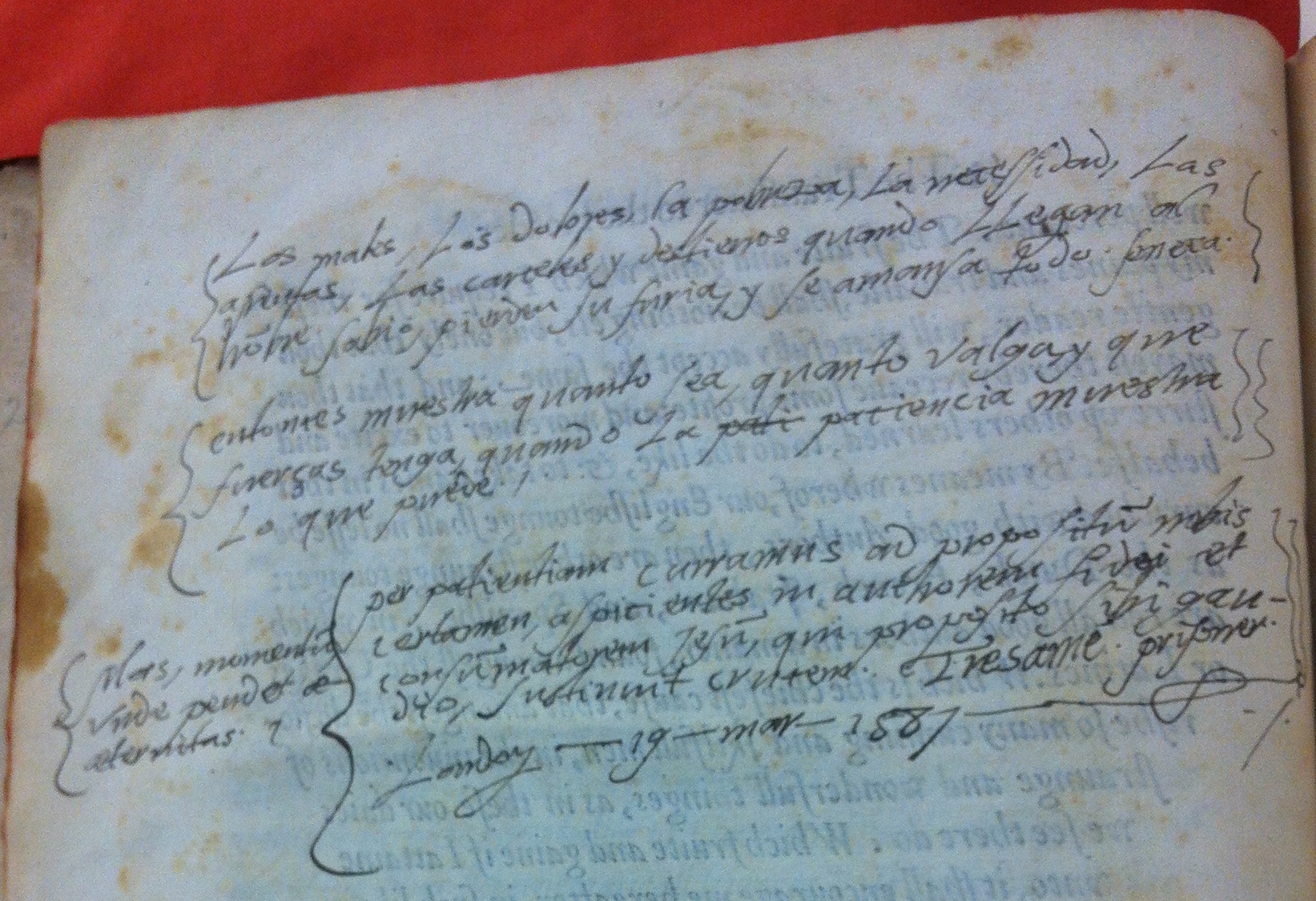

Annotations in Tresham’s Euclid, CUL Adams 4.57.1. By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

It quickly became obvious that this ‘criminal’ was Sir Thomas Tresham, a gentleman architect and builder from Northamptonshire perhaps best remembered for his beautiful and symbolic triangular building, Rushton Lodge. In the 1580s, Tresham was placed under house arrest in Hoxton for Catholic recusancy, and his son would later be involved in the Gunpowder Plot. The date of his imprisonment matched with the date that the author of the annotations had provided (‘19-mar-1587’), and ‘Tresame’ was a version of his surname, adjusted to bring out his obsession with the number three, especially the three-in-one of the Trinity. The copy of Billingsley’s Euclid I was reading, then, had surely once belonged to Tresham, and I was seeing fascinating evidence of his own treatment of this book.

Rushton Triangular Lodge, Northamptonshire.

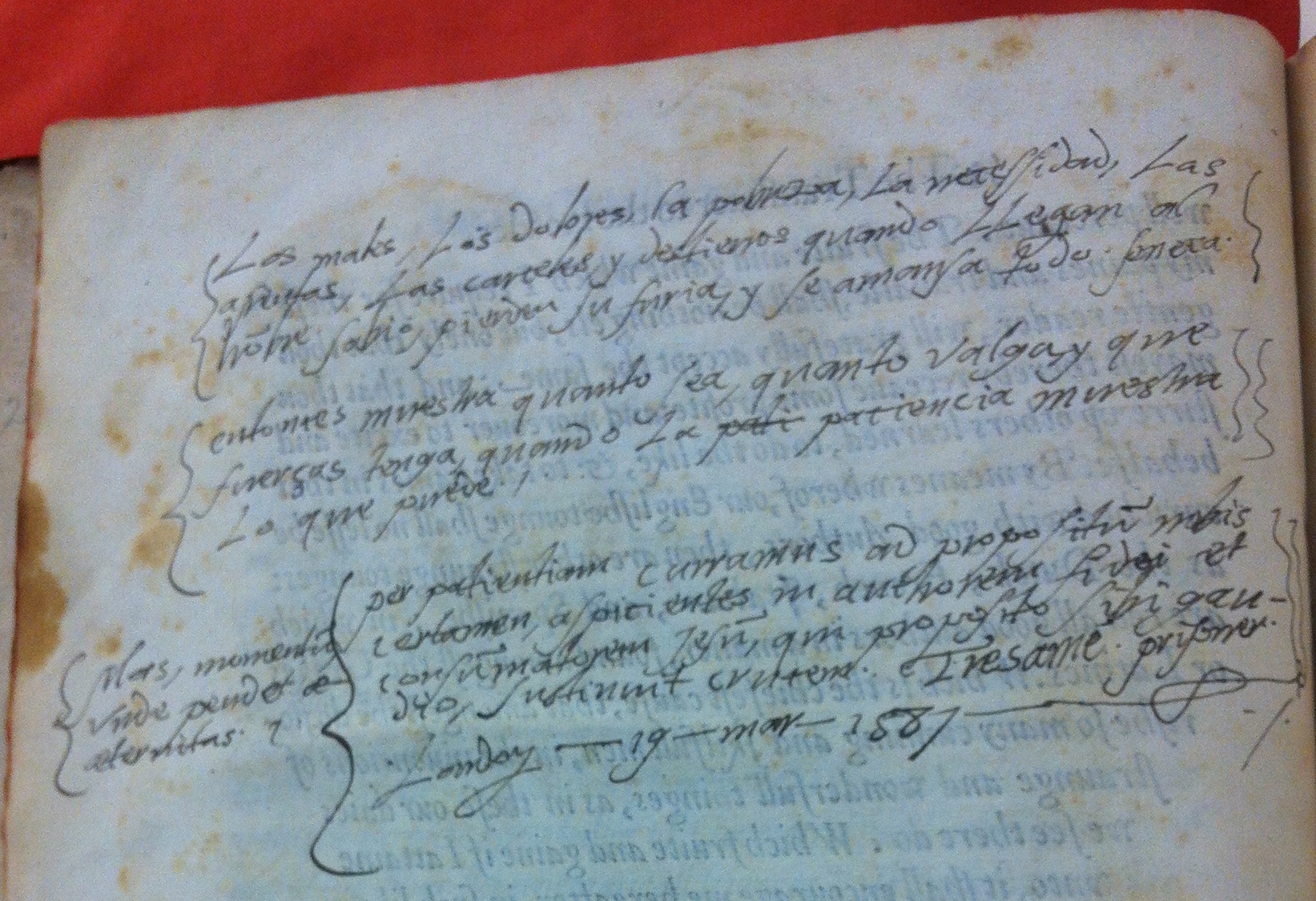

The simple bit (identifying the author) done, I now needed to decipher what Tresham’s annotations meant, and why they existed at all. Putting my small Spanish and less Latin to work, I was able to slowly piece together fragments of quotation. The single Latin sentence proved easy to find in the Vulgate Bible—it had been lifted directly from Hebrews 12:1-2—and one sentence of the Spanish was helpfully preceded by the word ‘Seneca’. To find its exact location in Seneca’s work, though, I had to translate the Spanish into English and then again into (very shaky) Latin, searching online editions of all Seneca’s writings in both languages to see if I would hit upon it somewhere. Eventually I did, and was able to pin the sentence to Epistulae morales 85.41: ‘Grief, poverty, indignities, imprisonment, exile: these should be feared everywhere, but when they come upon the wise man, they are tamed’. Upon the recommendation of my supervisor, Gavin Alexander, I began poring over the rest of the Epistulae morales: it seemed probable that if one annotation was a quotation from there, others might be also. After hours of trawling, I managed to trace all but two of Tresham’s annotations to the Epistulae morales.

More Tresham annotations in CUL Adams 4.57.1. By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Tresham’s Spanish constructions, however, vary in their degree of translational exactness: sometimes they are close to Seneca’s original Latin, sometimes they are very loose. This, I believe, provides the key to understanding precisely what Tresham was doing that day whilst under house arrest in London. The dull hours of imprisonment must have passed slowly, and offered Tresham a quiet opportunity to sit down and read. The location of his annotations suggest that he read all of Dee’s preface, and used it as a springboard for recalling snatches of his previous reading (Seneca, the Bible) and for practising his foreign languages (Latin, Spanish). He almost certainly did not have a copy of Seneca with him, and he probably did not own a Spanish edition at all. That he chose to write such snatches of Stoic wisdom in a book of mathematics is surely no coincidence. As a devotee of architecture, Tresham attributed great significance to lines, angles and numbers, and reading Dee’s words on the importance of mathematical labour to a truly spiritual existence seems to have inspired his own philosophical reflection. In his annotations, mathematics becomes a grander tale of humanity, brotherhood, life and death. ‘What good is there for me in knowing how to divide an estate into parts, if I do not know how to split it with my brother?’ ‘You know what a straight line is, but how does it benefit you if you do not know what is straight in life?’ (Epistulae morales, 88.11, 13).

Such tangential thoughts perhaps arose from Tresham’s unnerving personal circumstances, and just as he must have been unsure of the details of his future, so must we remain uncertain of the details of his past. My narrative is, I hope, convincing, but it is also necessarily hypothetical. This is the kind of thrill that work with material texts can offer: annotations and marginalia in books offer us flirtatious glimpses of a narrative, but from the physical evidence alone that narrative almost always remains incomplete. It is up to our imaginations to fill the gaps.

Joe Jarrett

If your library has a subscription, you can read Joe Jarrett’s article on the Tresham Euclid here.