A few weeks ago I made a pilgrimage to Great Yarmouth – not, as fellow early modernists might suspect, in the footsteps of Thomas Nashe, but on the trail of a temporary exhibition at the town’s Time and Tide Museum. Frayed: Textiles on the Edge brought together a poignant collection of historic and contemporary textiles associated with personal experiences of suffering. These pieces were framed as the work of outsiders – people ‘on the edge’ in some way. But – created by individuals whose circumstances kept them in a workhouse, prison, or hospital, or who were isolated by grief or mental illness – they were also the products of the experience of confinement, of being physically or mentally locked inside.

Several of the exhibits were sorrowful works of memoriam, a reminder that in previous centuries, the death of a child was much more common, and no less painful. Anna Brereton, the maker of a patchwork counterpane and bed hangings in the eighteenth century, must have been in an almost permanent state of recent bereavement, losing four children in their infancy, and her eldest son at the age of fourteen. As some of the other pieces revealed, the reality of death was known from a young age and like adults, children also marked out their grief in stitches. There was a sampler which had been started in 1833 by a little girl called Martha Grant, and finished the following year, probably by her sister, after Martha died at the age of eleven years. Between 1823 and 1829 another young girl, Louise Buchhotz, made three small samplers, each stitched in black thread, to mark the deaths of her parents and uncle. ‘For since she’s dead, for ever gone/ O GOD my soul prepare/ To enter into heavens high gates/ In hope to meet her there’, she stitched in memory of her mother, on a tiny piece of pale linen no bigger than a page of a pocket-sized book.

In an understated way, Frayed challenged typically gendered narratives of stitching in which embroidery is thought of as a solely female occupation. I did not know that after the second world war, manufacturers of embroidery silks set up ‘Needlework for H.M. Forces’ schemes, supplying recuperating soldiers with kits to ‘help relieve the inevitable boredom of idle hours’, and give ‘the satisfaction that arises from the practice of personal skill’. Relief from boredom and satisfaction at creating something beautiful out of the horrors of the past must have in part motivated John Craske, the maker of a large woolwork tapestry depicting the evacuation of Dunkirk. Craske spent long periods recovering from physical and mental illness following military service in the first world war, but poignantly, the piece is unfinished, for he died in hospital in 1943. The contemporary tapestry cushions made by men in prison through the social enterprise Fine Cell Work demonstrated that the therapeutic value of stitching for everyone, but especially those in confined conditions, is still taken seriously today.

The therapeutic value of stitching was painfully evident in another piece, loaned for the exhibition from the V & A. Elizabeth Parker’s sampler was made around the year 1830, by a woman who worked as a nursery maid and endured cruel treatment from her employers. In letters worked in tiny red cross-stitches on linen cloth, she set down a confessional account of ‘that willful design of selfdestruction’ which tormented her. Scripture providentially helped her out of the darkness: ‘the Bible lay upon my shelf I took it down and opened it the first place that I found was the fourth chapter of S. Luke where it tells how our blessed Lord was tempted out of Satan I read it and it seemed to give me some relief for now’. Her own writing stops mid-sentence, however – ‘What will become of my soul’ – leaving nothing else but the remaining blank space of her linen page.

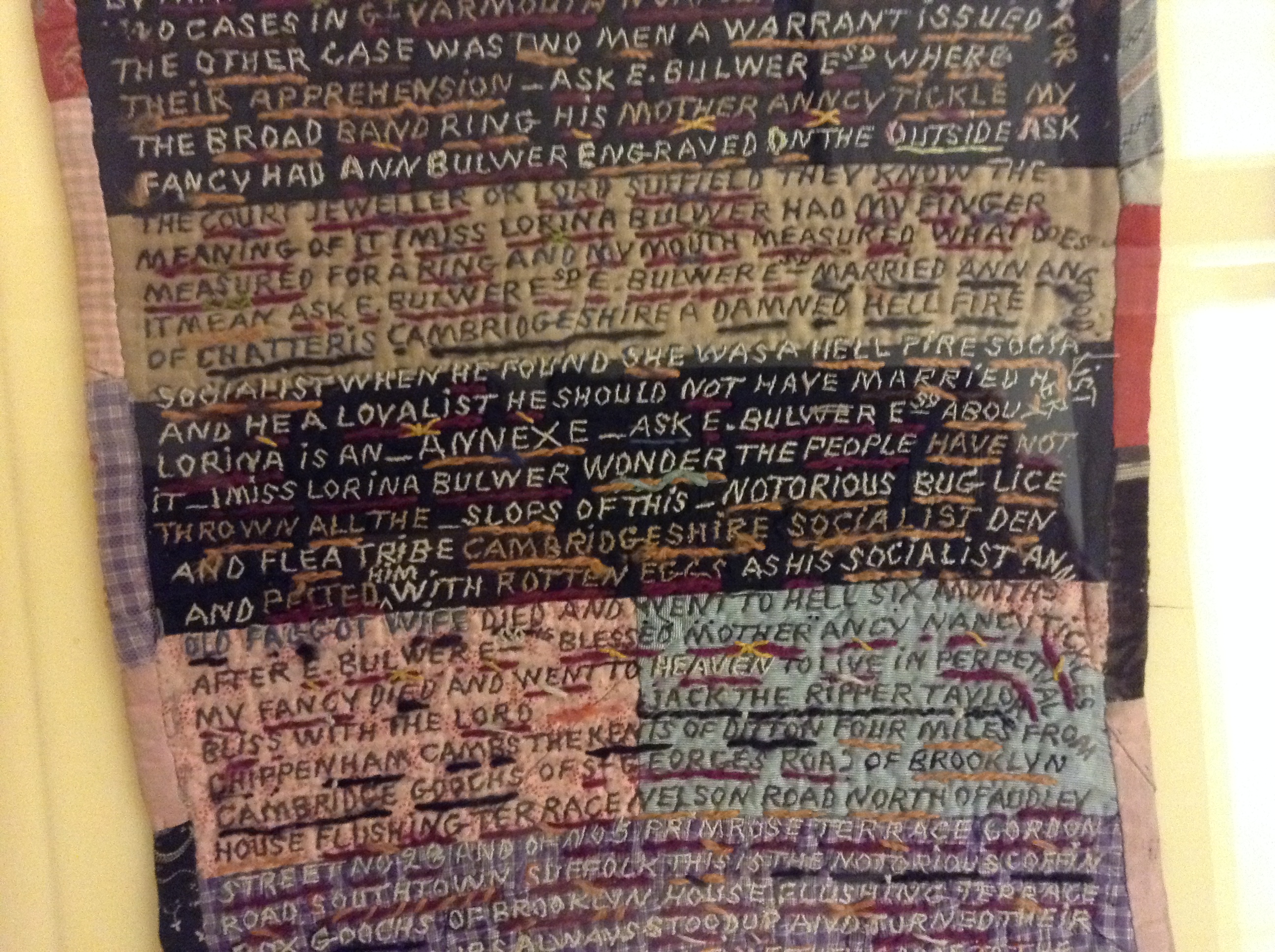

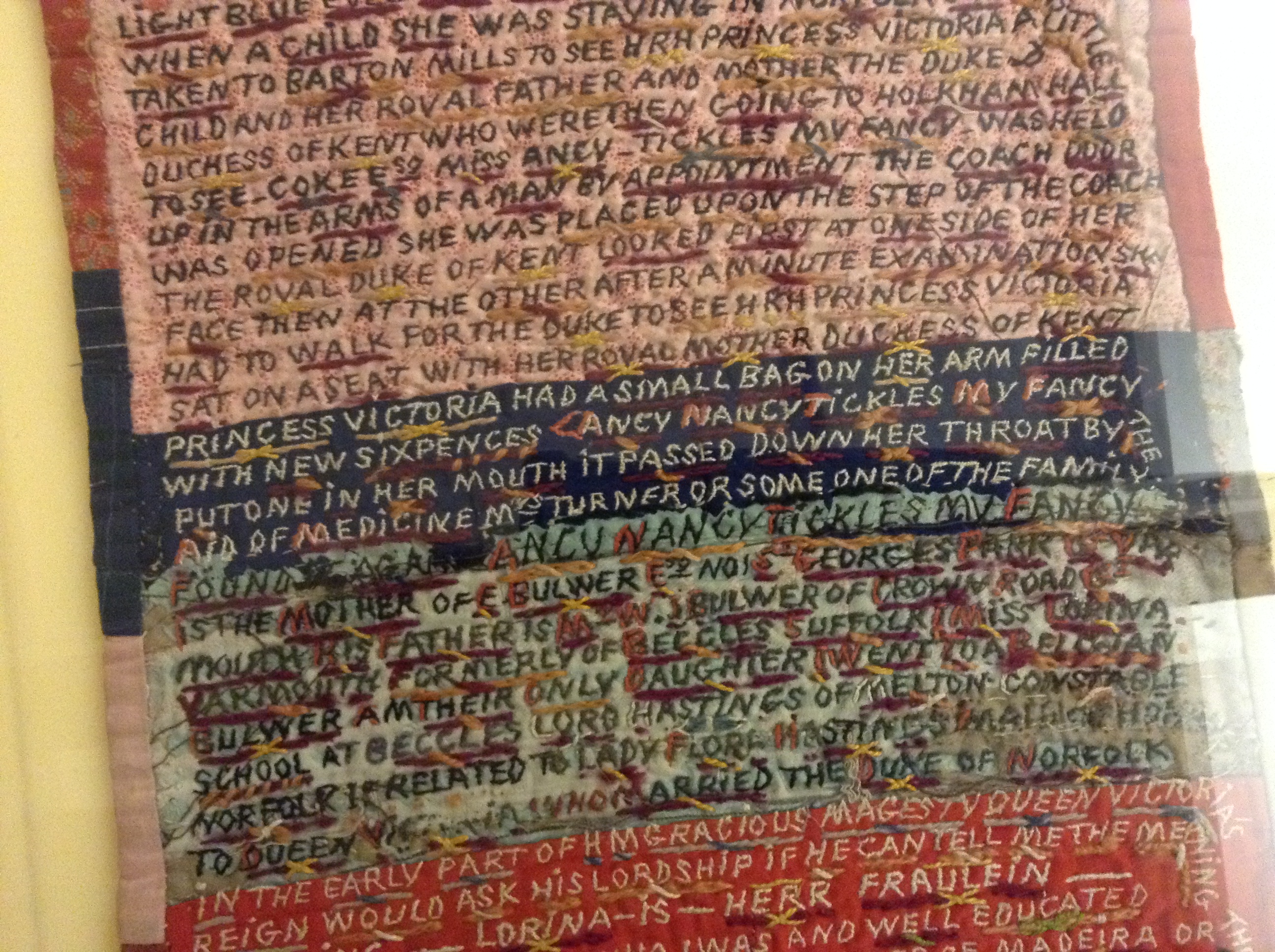

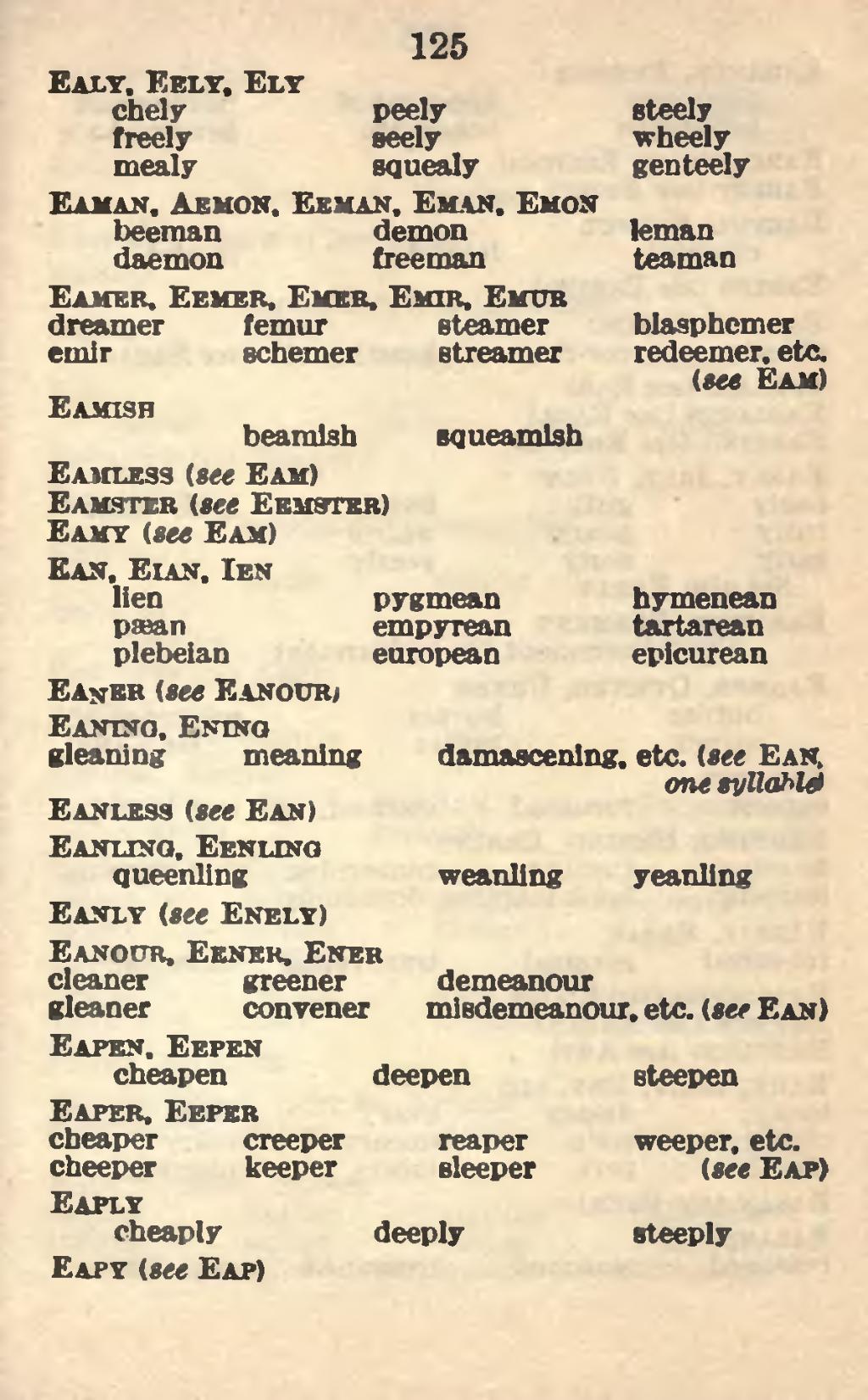

At the centre of the exhibition were two truly extraordinary stitched texts (pictured above and below) by a woman called Lorina Bulwer, who was an inmate in the ‘lunatic wing’ of the Great Yarmouth workhouse for several years at the beginning of the twentieth century. During her time there, Bulwer covered each of these three-metre lengths with densely embroidered text in which she expressed feelings of anger and frustration. Both pieces are made up of brightly coloured cotton fabrics stitched together, with a wadded lining and a backing fabric, like a quilt. Each individual letter is stitched through all of these layers. Writing in the first person, Bulwer offers a torturous working-out of her own identity. She is obsessed by names and places, frequently referring to herself by name, as well as to other people, including her own relations, members of the Royal family (she claims to be ‘Princess Victoria’s daughter’), and various towns and places in the East of England. A disturbing tangle of visceral, furious commentaries on people and situations apparently significant to her, Bulwer’s texts are impossible to summarise, but you can read transcriptions of them here.

The overall effect is one of unsettling, febrile tension between the text and its textile medium. Bulwer’s words are undoubtedly a rant, composed entirely in capital letters and without any punctuation – but their manifestation on the ‘page’ is the result of a slow process, in which each stitch has been individually formed. Writing with a needle is much slower than writing with a pen – another exhibit, Sara Impey’s machine-stitched contemporary quilt, made this point explicitly: ‘THE MOST DEMANDING ASPECT OF STITCHING IS TIME. THE STITCH DICTATES THE PACE’. Time, of course, is the one resource that imprisoned people, like Bulwer, often have most readily to hand. In her work, however, the inherently time-consuming, careful method of material composition contrasts with the angry, breathless quality of her words. It is clear that Bulwer intended her work to be read: she changes the colour of her thread according to the colour of the background so that the text is always clearly defined, and often highlights individual letters in contrasting thread where they cross over two different background colours. She underlines almost every word, and sometimes continues the text at right angles, along the borders. The cheery colours of the threads and background sit uneasily with the apparent bleakness of her experiences, and her implications of abuse. Bulwer’s desire to communicate is very evident, but this exhibition was the first time that both pieces have been displayed together (they are held in two different museum collections) – a sign, perhaps, of a general uncertainty about exactly how to read them.

Frayed: Textiles on the Edge has now ended, but the Time and Tide Museum (shortlisted for the Council of Europe’s Museum of the Year in 2006) is definitely worth a visit.

I recently caught up with my colleague Simon Jarvis’s essay ‘

I recently caught up with my colleague Simon Jarvis’s essay ‘