One of this winter’s exhibitions at the British Museum, ‘Journey through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead’, opens on Thursday. The exhibition website explains that the ‘Book’ was ‘not a single text but a compilation of spells designed to guide the deceased through the dangers of the underworld, ultimately ensuring eternal life.’ This is the first time that many of these unique works from the British Museum’s collection have been shown in a public exhibition. The oldest examples of these illustrated texts on papyrus and linen were written over 3,500 years ago, and they will be displayed alongside other objects connected to death, burial, and beliefs about afterlife in Ancient Egypt. The museum website doesn’t give away much more about these mysterious texts, but promises advanced technological elements in the exhibition to enrich the visitor’s experience and understanding of these fragile documents. There is a series of public lectures and events too, details available here. If readers of this blog can enlighten us further about these fascinating material texts after visiting the exhibition, please feel free to comment below!

The Magazine Modernisms blog (http://magmods.wordpress.com <http://magmods.wordpress.com/> ) is dedicated to modern periodical studies (1880-present). As the title indicates, MagMods is committed to examining modernism in all its diversity, including early, middle, late and post-modernism; high, middle-brow, and mass culture; magazines, newspapers, zines, and digital media. This diversity reflects the broad range of interests of the creators of Magazine Modernisms, who devised the plan to create a blog for the burgeoning field of modern periodical studies during the Summer Seminar on Magazine Modernism at the University of Tulsa, led by Sean Latham, Robert Scholes, and Cliff Wulfman, and generously funded by the NEH.

In addition to alerting readers about conferences, calls-for-papers, new publications, and other periodical studies news, Magazine Modernisms provides a forum for opinion, commentary, collaboration, query, and debate. One of our main aims is to inform readers about new and little-known digital resources for the study of periodicals.

The CMT is planning to offer occasional bespoke training seminars for graduate students confronting bibliographical, palaeographical, editorial or otherwise textual challenges in the course of their research.

These seminars will be held in the Wren Library in Trinity College, and will be hosted by the Wren Librarian, Professor David McKitterick.

If you think that you might benefit from such a seminar, you are invited to come to a preliminary meeting at 11am on Wednesday 3 November in SR-25 (second floor), Faculty of English, 9 West Rd.

Please email Jason Scott-Warren (jes1003@cam.ac.uk) if you are able to come on the 3rd.

‘Therein lies a tale’: literary manuscripts at St John’s College

As part of the University Festival of Ideas St John’s College Library will be holding an exhibition of literary manuscripts and rare books on Tuesday 26 October, with a free evening talk examining some of the items in more detail. The exhibition spans seven hundred years of English literature, including medieval manuscripts of Chaucer, Hoccleve and Lydgate, the first illustrated edition of Paradise Lost, first editions of Dickens and T.S. Eliot, a Philip Larkin holograph, and the science fiction of Douglas Adams and Fred Hoyle.

The exhibition will be held in the beautiful seventeenth-century Old Library of the College. In the evening Dr James Harmer (St John’s) will speak about a sixteenth-century manuscript of Sackvilles ‘Complaint of Henry Duke of Buckingham’, and Dr Ian Patterson (Queens’) will discuss ‘T.S. Eliot, the Hogarth Press, and Poetry Publishing’.

Exhibition open 10am-1pm, 2pm-4pm and 7pm-8pm in the Old Library, St John’s College

Free public talk at 6pm in the Fisher Building, St John’s College

All welcome.

This was the provocative title of BBC Radio 3’s Night Waves programme yesterday evening. Philip Dodd chaired a panel in Alnwick made up of novelists David Almond and Louise Welsh, historian Sheila Hingley, and Chris Meade, co-director of the Institute for the Future of the Book, which discussed the rising popularity of e-readers and the consequences of this new technology for readers, writers, and publishers.

Amongst the panel and the audience there was widespread agreement that reading books is a multi-sensory experience involving more than ‘reading text’. Hingley commented that a book is ‘more than a vehicle for text’, and we wouldn’t want to ‘curl up in bed with a piece of plastic’. Many audience members shared personal stories illustrating the importance of the physical as well as the intellectual and emotional pleasure of the book as a distinctive object to be shared and treasured – elements of reading which are absent from the experience of the e-reader.

Louise Welsh insisted on the democracy of the book in contrast with the expensive e-reader. She reminded us that a history of reading involves a history of access to knowledge, and suggested that because it costs hundreds times more than a cheap paperback, the e-reader is a less democratic medium for reading. As Jason’s most recent post here highlighted however, other manifestations of digital media have been responsible on an immeasurable scale for the democratisation of knowledge and writing. The panel praised the possibilities of the internet, such as fan fiction sites, through which readers can increasingly become writers themselves. David Almond pointed out that children and young people are a significant constituency of this democracy of reading and writing. While he said it was patronising to suggest that young people today are so familiar with screen technologies that books do not appeal to them, he noted that children’s literature in particular has been creative and experimental with different forms of and beyond the printed book, and should not be overlooked in this kind of debate.

Most enthusiastic about digital books was Chris Meade, who suggested that Dickens or Blake would have been excited by the opportunities offered by the e-reader. To be suspicious of the e-book on aesthetic terms is to succumb to nostalgia, he said; rather, we should resist defining ‘literature’ as something only found printed on paper, and embrace the possibilities of collaborative writing, print-on-demand, and new flexible boundaries of publication. Members of the audience drew attention to some valuable practical uses of the e-reader – a librarian from Newcastle commented that it could have significant benefits for borrowers who are limited by the size of print in books, and that with an e-reader housebound borrowers could potentially gain access to many more books than previously.

No matter how sleek and clever new screen technologies might be, the printed book is a ‘design classic’, someone put it. The e-reader looks as though it is here to stay, at least for the foreseeable future, and the panel agreed that we should think of this new relationship between the book and the e-book as not antagonistic and ‘either/or’, but as potentially mutually beneficial…

If you’re interested in hearing the whole debate, the programme is available to ‘listen again’ on BBC iplayer until 22 October 2010.

I heard a very absorbing lecture this afternoon by Dr Mathias Döpfner, the Humanitas Visiting Professor, who was taking time out from his day job as CEO of the German media corporation Axel Springer to offer Cambridge his thoughts on the digital revolution. He nailed his colours to the mast early on by saying that digitization was the fourth of mankind’s great inventions, on a continuum that included language, writing and print. And in the first half of his talk the internet was defined as an inherently anti-authoritarian space of free speech, the ideal culmination of the crusading efforts of generations of campaigners against censorship, and the bane of totalitarian regimes everywhere.

The second half of Döpfner’s lecture sketched out the other side of the argument, looking at the way we expose our private lives on social networking sites, and exploring the potential dangers of beguiling gizmos such as face-and-place recognition and global positioning systems. We may enjoy ‘geotagging’ our photos, or navigating unfamiliar cities without getting lost, but the technology that allows us to do this also allows us to be tagged and navigated in unprecedented ways. Of course, the companies that store our personal information and create new games for us to play claim to want only the best for us—‘Don’t be evil’, as Google puts it, plumbing unsuspected depths of banality—but then oppression frequently wears a smile. Döpfner’s conclusion (somewhat at odds with his initial premise) was that the internet is really nothing in itself. Like language, it is neither good nor evil; it reflects back the kind of society we want to be. Still, he concluded, only the worst kind of cynic would want to damn the internet as a threat to the free world rather than celebrating its enormous potential to release the unfree.

It was powerful stuff, but from the tone of the questions I suspect that some members of the audience were a shade more cynical than the speaker. The question of the relationship between capitalism and the internet was a significant unaddressed issue—do the free market in ideas and the free market in iphones have to go hand in hand? Are we in the West more interested in the spread of freedom or of profit? Or, to put it slightly less controversially (as did the Chair John Thompson in an eloquent final question), what relationship should there be between private companies and governments in regulating the web—given that the former act chiefly in their own interests, rather than in ours?

This is a tale about mirrors. My plight is that of the Lady of Shalott: ‘moving through a mirror clear / That hangs before me all the year, / Shadows of the world appear’. My shadows are those of the rare books reading rooms in research libraries throughout the country, of readers and librarians moving in and out of view (or of a sunny day observed through two mirrors, through the glass of a window). But my focus, like the Lady’s on her loom, is firmly on the book in front of me: John Donne’s XXVI Sermons (1660/1).

To explain: as the Research Associate for The Oxford Edition of the Sermons of John Donne, I am collating as many copies as possible of all the early prints of Donne’s sermons. Donne’s autograph manuscripts that may have ended up as copy text in the print shop have disappeared without a trace, hence my job involves establishing the best possible text from print, taking account of each and every variant introduced throughout the long and laborious printing process of three large folios and various quarto books.

Collating happens with the help of ‘Hailey’s Comet’, a so-called optical collator. In short, this is a set of portable mirrors on anglepoised stands which allow me to see simultaneously a page in front of me (the actual book in question), and a reproduction on a laptop screen of another copy of the same book. By superimposing the two images (rather like using transparencies) by endlessly twisting and turning the mirrors, and by unlearning my dominant eye’s impulse to see one but not the other image, my brain finally marries both images, after which any variant on the page jumps out in full 3D. The experience is not unlike watching a 3D movie. The printed page gains real visual depth, and the vagaries of early modern printing practice (and XXVI Sermons is a terribly printed book) come sharply into focus. ‘Hailey’s Comet’, devised by Carter Hailey, is a miracle of invention, mostly due to its portability: whilst the very first Hinman collator (allowing Charles Hinman his groundbreaking observations about the composition of Shakespeare’s 1623 Folio) required a large room to house it, the Comet fits neatly into a backpack with room to spare for lunch.

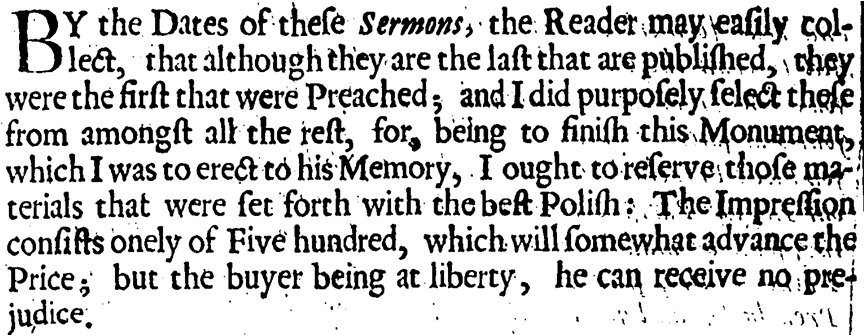

Cambridge University Library is a particularly helpful place to work on Donne’s XXVI Sermons, since the library acquired, in 1982, the collection of Sir Geoffrey Keynes, famous surgeon and bibliographical scholar (see http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/deptserv/rarebooks/keynes.html). The Keynes collection comprises around 8,000 items, many of which are still kept in Keynes’s own bookcases at CUL, in what is now known as the Keynes room. Apart from many other influential works on English literature and bibliography, Keynes produced the authoritative bibliography of Donne, and owned a significant amount of early printed books by the author, including 4 copies of XVII Sermons. The book in question was issued with three variant title pages, and Keynes owned an example of all three. Keynes’s books made for extremely rich pickings for me as collator. We are fortunate to have the very exact number of XXVI Sermons that were printed, since this information is relayed by John Donne the younger, who saw the volume through the press:

Whether or not Donne the younger was simply fleecing money out the pockets of the seventeenth-century book buyer remains difficult to know for certain – XXVI Sermons is not remotely a ‘polished’ book and so Donne Jr was disingenuous on at least one count. Yet let us for the moment accept that 500 copies were indeed printed. From this print run I have managed to retrace around 50 copies, a very significant amount in light of the normal expected chances of survival for early printed books. Thus around 10% of the print run survives, 1% of which (5 copies) can be consulted side by side at CUL (and a further two, respectively, at King’s and Newnham Colleges) – an unrivalled opportunity to observe print variants and other bibliographical features of the book.

Collating renaissance printed books is an unsettling experience. Firstly comes the initial feeling of seasickness (I have also heard reports of migraines) when tricking your brain that you are seeing one, not two pages at once. But seasickness abates with practice. Physical discomforts overcome, for the intrepid collator the printed page will never give the same static impression of type upon page, as I used to see it. Rather, the early printed page becomes a living organism. Each single impression of each page in a copy of the Sermons is subtly, sometimes unsubtly, different: variously inked, occasionally with a hair caught between press and paper, sometimes with some type knocked out of place, sometimes with the furniture of a forme rearranged, and frequently, with the type reset to correct mistakes. This comes as no surprise to anyone who has ever edited anything from early print – but for the EEBO generation nurtured by the single digitised copies that are freely downloadable, this lesson must continually be taught. Collating books teaches one about the sheer physicality of the printing process, and about the fact that printed texts are not the stable entities they are purporting to be.

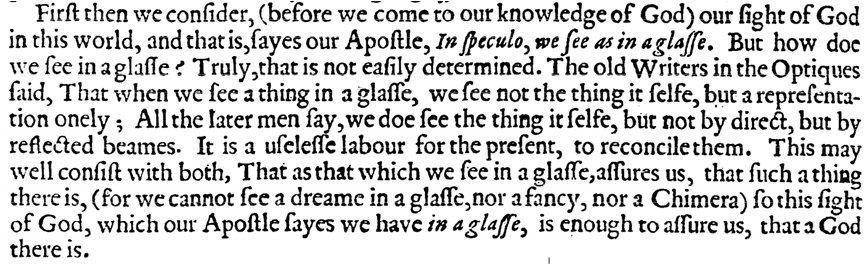

In early modern thinking the mirror features as a pervasive metaphor and poetic image, and also as a frequent object in, and subject for, scientific and theological enquiry. Examples abound, so I shall limit myself to one:

So speaks Donne, from his Easter sermon for St Paul’s, 1628 (on I Cor. 13.12, ‘For now we see through a glasse darkly, but then face to face; Now I know in part, but then I shall know, even as also I am knowne’). I will resist the temptation to wrench Donne’s carefully crafted prose out of context: for example, how the sermon text observed through the collator is ‘but a representation onely’; and how the sermon itself, dramatic performance piece par excellence, is only imperfectly present, as if by ‘reflected beams’, in the printed text; and how whatever Donne wrote in manuscript can only imperfectly be reconstructed from print, as if reading ‘through a glasse, darkly’.

Granted, in the already arcane field of textual criticism, the optical collator takes the prize for most unlikely contraption to take into a library. Yet renaissance readers loved mechanical reading aids (see Ramelli’s famous ‘Reading Wheel’; for a recent attempt to actually build this fantastical machine, see here: http://greg.org/archive/2010/09/20/on_the_making_of_the_lost_biennale_machines_of_daniel_libeskind.html#more).

We might not catch our glimpse of God, yet in light of such reading machines it feels curiously appropriate to examine the renaissance book through two collating mirrors.

Sebastiaan Verweij is the Research Associate for The Oxford Edition of the Sermons of John Donne (see http://www.cems-oxford.org/donne ). He previously worked on Scriptorium at Cambridge (http://scriptorium.english.cam.ac.uk/ ) and designed this CMT website, so this Gallery exhibit is his parting shot.

1. The Hinman Collator. Courtesy of http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/media_player?mets_filename=evm00000595mets.xml.

2. The Comet (and Sebastiaan) at work in the Cambridge University Library.

By now it will be presumably be hard to get uncorrected copies of Jonathan Franzen’s new novel Freedom, forty-six million printed pages of which were pulped last weekend after the author discovered that they were riddled with errors. Viewers of Friday’s ‘Newsnight Review’ were treated to a delightful bit of footage (sadly not yet available on Youtube) in which the author stopped in the middle of the extract he was reading to camera, declared that his English copy was full of mistakes, and uttered a heartfelt expletive. In a faraway printing firm, the hand that double-clicked the wrong computer file was doubtless being slapped, hard.

So far as I’m aware, none of the reviews–even those in the Times Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books, which dared to suggest that Franzen’s was not the novel-to-end-all-novels–mentioned the typos and unrevised passages that got the author’s goat (either they were skimming, or they had been sent the American edition). The British press, which is not renowned for its ability to resist a good pun, mostly neglected to point out that Franzen’s previous bestseller had been entitled ‘The Corrections’. But the papers did dredge up some fine examples of previous pulpings, including a Pasta Bible that told readers to add ‘salt and freshly ground black people’ to their tagliatelle, and the ‘Wicked Bible’ of 1631 which instructed, between ‘Thou shalt not kill’ and ‘Thou shalt not steale’, ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’. (The last was apparently an act of industrial sabotage, rather than a mistake).

In Spenser’s Faerie Queene (1590), the snaky monster Error spews out ‘vomit full of bookes and papers’ when she is vanquished by a passing knight in shining armour. Outside the world of poetry, she’s clearly still on the rampage.

History of Material Texts Seminar: Michaelmas 2010

October 6th, 2010Events, Seminar Series; Andrew Zurcher This term’s seminars in the History of Material Texts are as follows.

This term’s seminars in the History of Material Texts are as follows.

Thursday 14 Oct, 5.30, room SR-24 in the Faculty of English Prof. Anne Coldiron (Florida State University) Printers Without Borders: Translation and Literary Transnationalism in the Long Sixteenth Century

Thursday 11 Nov, 5.30, room SR-24 in the Faculty of English Prof. Jim Secord (HPS, University of Cambridge) Nebular Visions: Image and Text in John Pringle Nichol’s Architecture of the Heavens

All are welcome. The seminar is a forum for research across disciplines and across periods, for all those interested in the history of the book, bibliography, histories and theories of reading, and the intersections between intellectual history and material culture, including the creation, production, publication, distribution, reception, transmission, editing and subsequent history of texts as material objects in manuscript, print, digital media or other forms.

For information, contact this term Daniel Wakelin (dlw22@cam.ac.uk).