Has anyone been to ‘The Sculpture of Language’, a current exhibition curated by Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy at the Tate Liverpool? It’s one of the three parts of the DLA Piper series ‘This is Sculpure’ (the other two are ‘Sculpture: The Physical World’ and ‘Sculpture Remixed’), each of which has been developed by Tate curators alongside leading cultural figures from a range of disciplines. From the Tate collection Duffy has chosen works from 1699 to the present day which engage in some way with written words, including pieces by David Kindersley, Eric Gill, Sonia Delauney, and Salvador Dali. Duffy has contributed a specially-written sonnet, ‘POETRY’, to the exhibition too. More can be read about ‘The Sculpture of Language’ here. I’m interested in how this kind of exhibition investigates the ways in which artists working with different media respond to words and language, and invites us to reconsider text in the context of other art forms. If you’re in Liverpool during the next few months, this certainly looks worth a visit.

A friend has just alerted me to a website displaying perhaps the most material text any of us is ever likely to encounter–http://ny.bloomsburyauctions.com/detail/NY014/383.0. The auctioneer has done his/her best to make sense of this magnificent artefact, but perhaps followers of this blog can offer fuller meditations upon its meaning?

Yesterday I learnt that, if I want to look at a book in the Middle Temple library, I’ll have to pay £30 for the privilege. ‘As a private library, we are forced, by the rules of the Inn, to charge non-members for access’. I immediately started fuming; if every library in the land starts charging for access, a lot of serious research is going to become impossible. But perhaps this is the future, and we’re all going to have to get used to it. Are other libraries already routinely charging their academic users? Are librarians contemplating the introduction of charges, as budgets get squeezed and educational institutions become more and more private?

Beneath the magnificent barrel-vaulted ceiling of the Playfair Library in Old College, Edinburgh, over two hundred people gathered on a mid-July weekend for the third Material Cultures conference organised by the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for the History of the Book.

A glance through the elegantly produced programme reveals the diversity of the disciplines and backgrounds represented. Over the three days, discussions of (to give an incomplete list) the buying, selling, publishing, giving, sharing, collecting, saving, printing, editing, listing, archiving, translating, illustrating, annotating, dedicating, digitising, indexing, and binding of material texts reached far beyond the traditional scopes of ‘bibliography’ and ‘book history’. Some of the panels focussed on particular people and places; in light of our location there were panels dedicated to the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland, to the history of Shakespeare scholarship in Edinburgh, and to some specific manuscript anthologies in Renaissance Scotland. Other panels used broader themes such as ‘Printers Across Borders’, and ‘The Business of Books’ to bring together material texts usually separated by geographical and chronological distance. The titles of quite a few other panels and the papers within them were mystifyingly vague, and as we were not supplied with abstracts of papers this meant a certain amount of advance guessing was necessary. This in itself was a reminder of the sweeping consequences of ‘material culture’ and the challenges we face in talking meaningfully about texts as ‘material’ in inter- and intra-disciplinary ways.

Indeed, such was the scale and breadth of the conference that it sometimes felt that several conferences were happening simultaneously. Most noticeably, it was certainly possible to fill three days listening to papers about the digital: digital archives, digital texts, digital editions, screen media, virtual museums, digital bindings, Kindles, hypertexts, and e-books all featured, demonstrating the importance of this rapidly developing field of technology, research, and practice. It was equally possible, however, to experience a conference relatively free from the d-word, although in the final plenary session Jerome McGann warned us not to underestimate the ever-increasing complexity of the relationship between scholars, libraries, and digitisation.

In the opening plenary session, Roger Chartier asked some searching questions about the history of attitudes towards authorial manuscripts, suggesting the need to appreciate the function of the library or archive as the site of preservation not only of material texts, but also of particular sets of historically specific ideas and conventions about authorship. Later that day the second plenary session starred Peter Stallybrass, whose presentation developed some of the ideas he introduced at the inaugural CMT conference earlier this year. Pointing out the limitations of the traditional division we set up between ‘print’ and ‘manuscript’, he urged us to consider print as a medium which incites manuscript: ‘printing for manuscript’. In his lavishly illustrated talk, Stallybrass demonstrated how we can look again at everyday printed ‘blank’ documents which require completion with handwritten details. Immigration landing cards, cheques, birth certificates and field service postcards, for example, were juxtaposed with seventeenth-century funeral tickets. By viewing print as a medium which crucially creates space for manuscript, Stallybrass argued, we might consider afresh the presence of handwriting in early printed books, and think further about how we differentiate between ‘print’ and ‘manuscript’.

Such questions of terminology, definition, and categorization underpinned many of the discussions at this conference. The ‘material text’ crosses many disciplinary boundaries, and as scholars, librarians, and readers, our task is to continue to explore the terms and language with which we may most fruitfully talk about the ‘text’ as something ‘material’.

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHERN RENAISSANCE 3.1 – CALL FOR PAPERS

The Journal of the Northern Renaissance is currently inviting submissions for its third issue, on any aspect of the cultural practice of Northern Europe in the period 1450-1650, including literature, visual culture, philosophy, theology, politics and scientific technologies.

We are particularly interested in studies exploring alternative cultural geographies, challenging existing conceptualizations and periodizations of the Renaissance in the North, and/or continuities and ruptures with earlier and later epochs. Part of our intention, however, in having an open, unthemed issue, is to gauge where the most interesting work is being done and what questions are being asked by scholars working on Northern Renaissance culture across a wide range of disciplines. We are very keen on submissions in the field of material culture, or material texts.

Submissions should be sent to the journal by 31st August 2010. Potential contributors are advised to consult the submissions page of our website for details of the submissions procedure and style guidelines. Enquiries regarding submissions can also be sent to us

here.

–

Journal of the Northern Renaissance (ISSN: 1759-3085)

http://northernrenaissance.org

Editors: Patrick Hart and Sebastiaan Verweij

Reviews Editor: Gillian Sargent

c/o

University of Strathclyde

Dept. of English Studies, Livingstone Tower

26 Richmond Street, Glasgow G1 1XH

News today that Raymond Scott, an antiques dealer, has been jailed for eight years for handling a copy of the 1623 Shakespeare First Folio that had been stolen from the Durham University Library in 1998. In his summing-up, the judge claimed that Scott’s motive for dealing in this ‘quintessentially English treasure’ was ‘financial gain’; in particular, he ‘wanted to fund an extremely ludicrous playboy lifestyle in order to impress a woman [he] met in Cuba’.

Such a judgment confers a prophetic quality on one of the more curious aspects of Anthony James West’s magnum opus, a history of the Folio in four volumes, which began to appear in 2001. West calibrated the price of the Folio in the first three centuries of its life against the cost of bread (44 loaves on its first publication, 5,000 loaves by the 1850s). But for the twentieth century he instead compared it with the cost of ‘three luxury items … a Purdey shotgun, Russian caviar, and a Jaguar motor car’. ‘The purchaser of these items,’ he suggested, ‘is likely to have had certain characteristics in common with the purchaser of a First Folio–such as disposable wealth, aspects of lifestyle and taste, and perhaps the wish for “the esteem and envy of fellow men”‘. Or women, we might now add, with an eye to Mr Scott.

When West compiled his Census of Folios, documenting the whereabouts, provenance and physical condition of every surviving exemplar, he noted that the Durham copy was unavailable for inspection because it had been stolen. Bought by John Cosin sometime before 1632, this copy was incorporated into Peterhouse library in Cambridge during the Civil War, while its owner was exiled in France, but was later recovered to grace the episcopal library on Palace Green in Durham, which Cosin endowed in 1669. It thus has a claim to be the first First Folio to have sat on the shelves of a public library.

It’s good to hear that the stolen book will soon be on its way back home. And West’s work, which renders any individual copy of the Folio instantly identifiable, ought to make any ludicrous playboy think twice before raiding the library.

First published June 2010

James Harmer, St John’s College

Fig. 1 St John’s College, Cambridge, Aa.4.48. By permission of the Master and Fellows of St John's College, Cambridge.

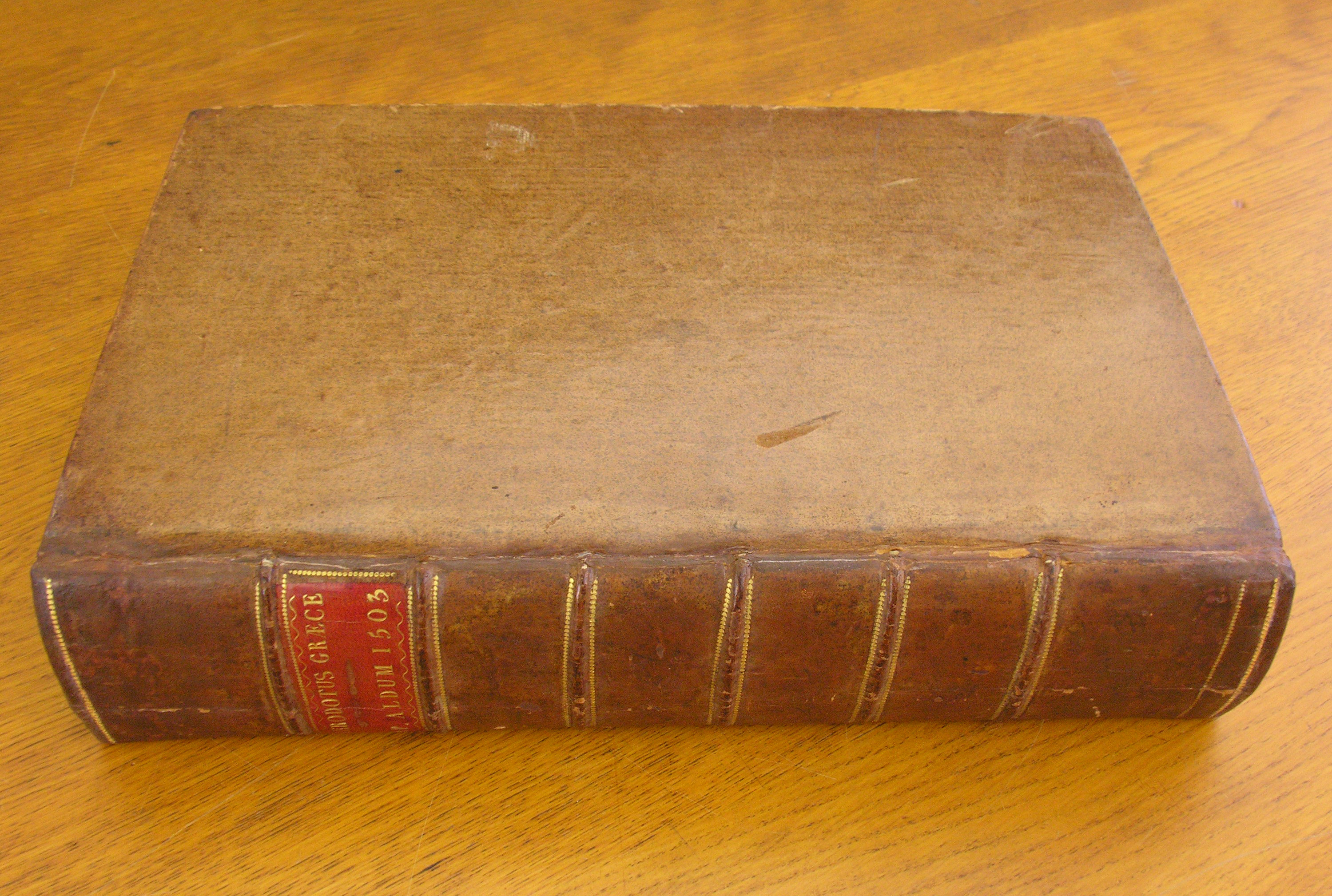

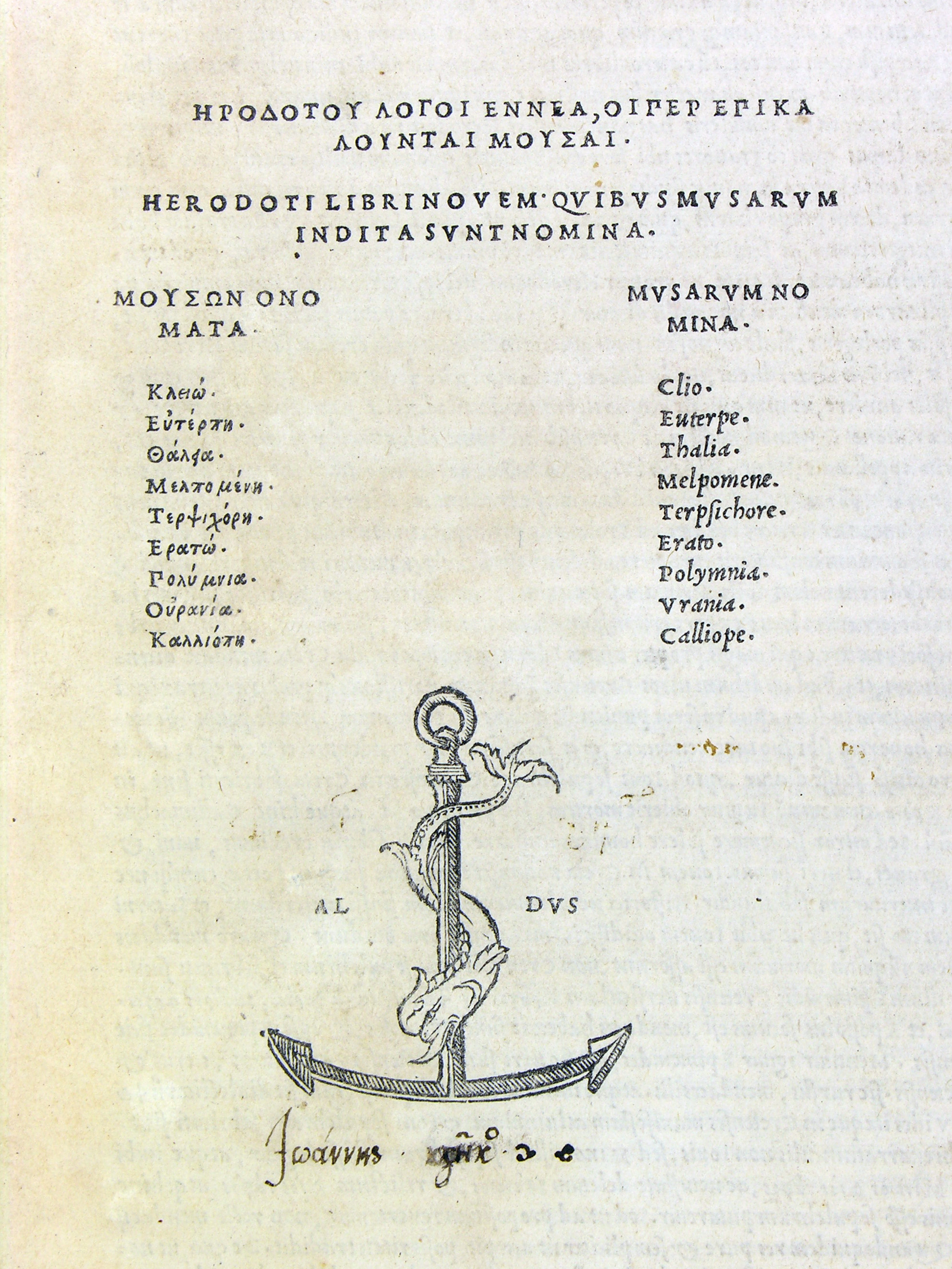

A landmark donation made this year to the St John’s College Library by Brian Fenwick-Smith will help future generations of researchers to study the life and work of Sir John Cheke (1514-1557), a figure who, as humanist tutor, classical scholar and author occupies a central place in the history of the English Renaissance. Fenwick-Smith’s donation of three Aldine texts of Greek history that were owned and extensively annotated by Cheke sheds a fascinating light on the intimate Renaissance relationship between scholarship and statecraft.

John Cheke was born in Cambridge and entered St John’s in 1526. He was tutored principally by George Day, another important figure from the College’s early history who was helping to make St John’s a major centre of what is now known as Renaissance humanism. Humanism can be thought of as a programme of educational, cultural and religious reform which had its beginnings in Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries before spreading rapidly across Europe. Humanism’s chief focus was the study of the classical past – its history, languages, and thought – as a rich resource for the shaping of the whole person. Humanistic study taught one how to live both an examined private life and also a civic, public one. For humanists, scholarship and statecraft went hand in hand: what one found in the histories or poems or orations one studied could be applied directly to the way in which one lived one’s life and served one’s society. Someone with a humanist education could do all kinds of things: understand love, draft a law, write a poem, win a debate, interpret the Bible, and advise a prince. The acquisition of a volume such as this Aldine edition of Greek history – which comes in the wake of other recent donations by Brian Fenwick-Smith, including first editions of Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) and More’s Epigrammata (1521) – shows how much there is still simply to be unearthed, made available, and understood about the dynamic history of reading in this period. The role that continues to be played by College special collections in expanding and developing what resources are available is vital in enabling early modernists to do all kinds of things – pedagogical, bibliographical, conceptual – with those resources. In this sense, then, such donations and such libraries are very much legacies of the humanist project itself.

At St John’s, Cheke excelled at the study of the classical past and its languages, and he played a critical role in developing an understanding of the language at a time when the study of Greek was in its infancy in England. Cheke was admitted as a Fellow of St John’s in 1529 and took his BA in 1530. During the 1530s, Cheke concentrated on improving his Greek studies, and became in 1540 the University’s first Regius Professor of Greek. It was also during this period at St John’s that he taught a number of Johnians who would go on to have distinguished careers, including William Cecil (Elizabeth I’s principal minister) and Roger Ascham (tutor to Elizabeth I). Cheke’s public profile grew further when he was plucked from Cambridge and dropped into the very centre of court life. In 1544, he became tutor to Prince Edward, to whom he taught, in Greek, the works of Aristotle and Plato. The Prince became King Edward VI in 1547, and in 1553, having remained close to Edward throughout his short reign, Cheke was appointed his principal secretary. Yet 1553 also brought the death of the young King, and the staunchly Protestant Cheke was to spend his last years struggling with life in Queen Mary’s Catholic England, spending time in exile and in prison before his early death.

Fig.2 Title page showing ownership signature of John Cheke. By permission of the Master and Fellows of St John's College, Cambridge.

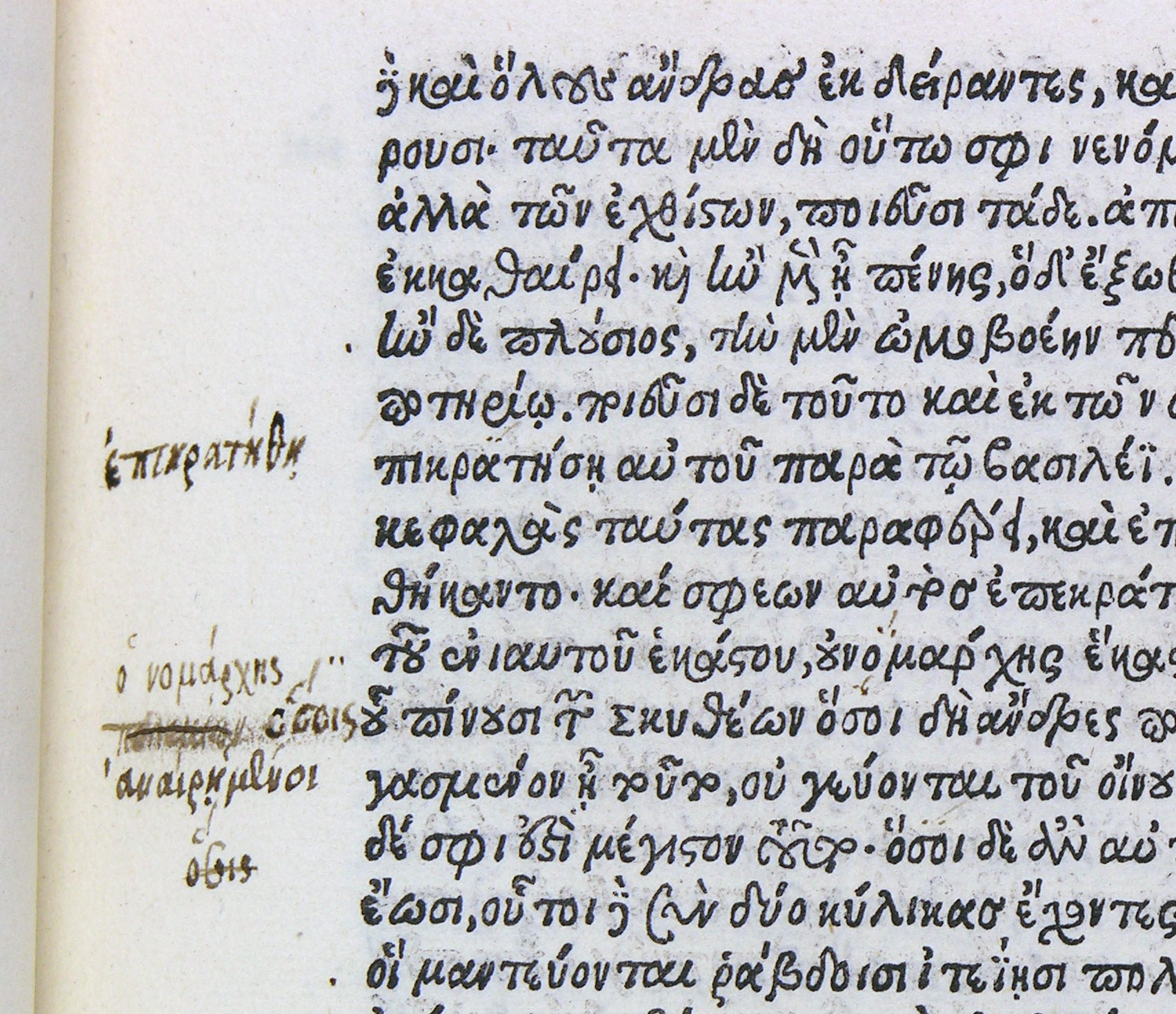

So there is a direct line to be drawn from humanist St John’s to the heart of the political and religious life of mid-Tudor England. Cheke’s work at Cambridge, and especially his distinctive study of ancient Greek texts, was what gave him the authority to advise a young King, help direct government policy, and play a prominent role in the English Protestant Reformation. The donation to the St John’s College Library of a book used by Cheke gives us a vital insight into this extraordinary Renaissance relationship between classical scholarship and the workings of society. The volume comprises three separate works of Greek history bound together in one folio volume: The Histories by Herodotus, The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, and the Hellenica of Xenophon. The first two works in this volume were printed by the Aldine press in Venice in 1502; the printing of the last work in the volume, the Hellenica, was delayed slightly until 1503 (Aldus was apparently nervous about not having enough manuscripts of Xenophon to work from). Together, these texts form a history of Greece that stretches from the Persian wars, through the Peloponnesian war, and which ends, with Xenophon picking up straight after Thucydides, in 362 BCE. The collation of this copy of Aldus’ edition is complete, its texts beautifully clean. The volume is bound in eighteenth-century English calf, and the pages have been cropped slightly by the binder: this affects some of the annotations in the margins of the Hellenica but leaves the marginalia pertaining to the other texts unaffected. The volume bears the bookplate of Sir George Osborn (1742-1818). Osborn was a descendent of Peter Osborne (1521-92), who was a close friend of Cheke’s and one of the executors of his will. Osborn was responsible for the education of Cheke’s son, Henry (c.1548-1586), and it is possible that some of the marginalia which appear in the volume are in the mid-Tudor hand of Henry Cheke. There are certainly two hands at work in the margins of the volume, and perhaps more: at this stage, however, it is at least clear that Cheke’s hand is a very extensive presence in those texts by Herodotus and Thucydides.

- Fig. 3 St John’s College, Cambridge, Aa.4.48, sig. 2H6r. Cheke notes in the margin of the Histories of Herodotus that the Scythians made ‘conquests’, and then notes that the text is describing ‘The prizes the Scythians bear away’. By permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

Cheke’s ownership signature appears in Greek on the title page, and Cheke goes on to write down hundreds of individual Greek words and phrases in the margins. Just when he made these notes is a question that would benefit from further investigation, but judging by comparable samples of his hand and the arc of his teaching and study of Greek, it is reasonable to suppose that Cheke annotated the volume during the 1530s. Sometimes one can glimpse Cheke extending his Greek vocabulary: he notes the words for such things as a fawn, a small horse, a ferryman, a vessel for carrying water. At other, more significant moments, Cheke is interested in finding the word that best captures a passage of military action. Several times he comes across descriptions of battles where one side is being overwhelmed by the other: Cheke notes the Greek for being ‘squeezed’ or ‘crushed’ (see, e.g., Peloponnesian War, sig. G2r). Relatedly, in reading Thucydides, Cheke notes passages that describe a tactical retreat or negotiated alliance (Peloponnesian War, sigs A5r, K6r). In the Histories of Herodotus, Cheke notes that when they made a conquest, the Scythians would carry away prizes – the scalps and skins of their enemies (sig. 2H6r). He consistently has an eye for the detail that distills a passage, and makes a habit of finding in these texts a single Greek keyword which encapsulates a chunk of writing. Cheke picks out words that are moral, political, action-packed. Here is a passage from Herodotus about ‘retribution’ (Histories, sig. G5r); here another touching on the ‘barbaric’ (Histories, sig. 2S2r). Here is a passage in Thucydides about being ‘suspicious’ (Peloponnesian War, sigs B5r, L5r), here another about handling ‘grievances’ (Peloponnesian War, sig. L1r). And here – close by – is a good example of ‘wickedness’ (Peloponnesian War, sig. L1r). What Cheke is doing with these books is extracting examples of policy and conduct, and finding Greek words and meanings for those examples that can refine or enrich English words and deeds. This is the stuff, these are the textual activities, out of which good courtiers, good advisers, and good Kings are made.

Coincidence and Curiosity: A Tale of Discovery in the Old Library at Queens’ College

July 28th, 2010Gallery; adminFirst published April 2010

Karen Begg, Librarian, Queens’ College

|

A happy coincidence of scholarship and curiosity resulted in the recent discovery of three masterpieces of 14th century Italian manuscript illumination that for many years lay forgotten in a plan chest in the Old Library of Queens’ College. In 2007, when working on another project, Dr Stella Panayotova, Keeper of Printed Books and Manuscripts at the Fitzwilliam Museum, identified the pieces as the work of Pacino di Bonaguida, a prolific and distinguished Florentine artist. Since their identification, the miniatures have travelled the globe in a unique collaboration between the College, the Fitzwilliam and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, to learn more about the artist, his world and his techniques. As College Librarian, I am delighted to recount the Cinderella-like tale of discovery that has enabled a few more pieces of the ‘Pacino jigsaw’ to be fitted together and to report on a future for our miniatures that promises more than a return to the Library’s plan chest. |

||

|

The story begins with Stella’s visit to examine Dutch material for inclusion in the first volume of the Cambridge Illuminations catalogues [1]. Stella kindly agreed to glance at some cuttings that we knew little about, but suspected were of North Italian, early Renaissance origin. Stella excitedly and immediately shared her suspicions that these were lost leaves from a Laudario painted in Pacino’s workshop that she, together with other art historians around the world, had been researching. A laudario is a manuscript comprising lauds, or songs of praise in Italian that were used by lay communities to celebrate religious feasts or Saints’ days. The Queens’ leaves depict the Martyrdoms of St Christopher, St James the Great and St Lucy. The Fitzwilliam had been given two comparable leaves early in the 20th century and, coincidentally, had recently found a third – all from the same Laudario. Stella’s subsequent scholarly article on the Queens’ and Fitzwilliam leaves [2] summarises much of what is known about the artist and this Laudario, Pacino’s most renowned work, which is believed to have been commissioned by wealthy patrons for the Compagnia di Sant’ Agnese in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence [3]. Stella describes in detail the content and context of each leaf and the art historical relevance of its discovery. |

||

|

During the next year, other specialists, including two experts from the Getty Museum, viewed our leaves and confirmed Stella’s opinion. In early 2009, Queens’ was invited by the Getty to take part in scientific research, the findings of which would feature in an exhibition planned for 2012 entitled “Florentine Painting and Illumination in the Time of Giotto”. This offered a unique opportunity to contribute to a significant and interesting study, and the College’s Governing Body unhesitatingly agreed to allow our manuscripts to travel to the Getty Museum, where non-invasive analysis of pigments and structure could be undertaken. |

||

|

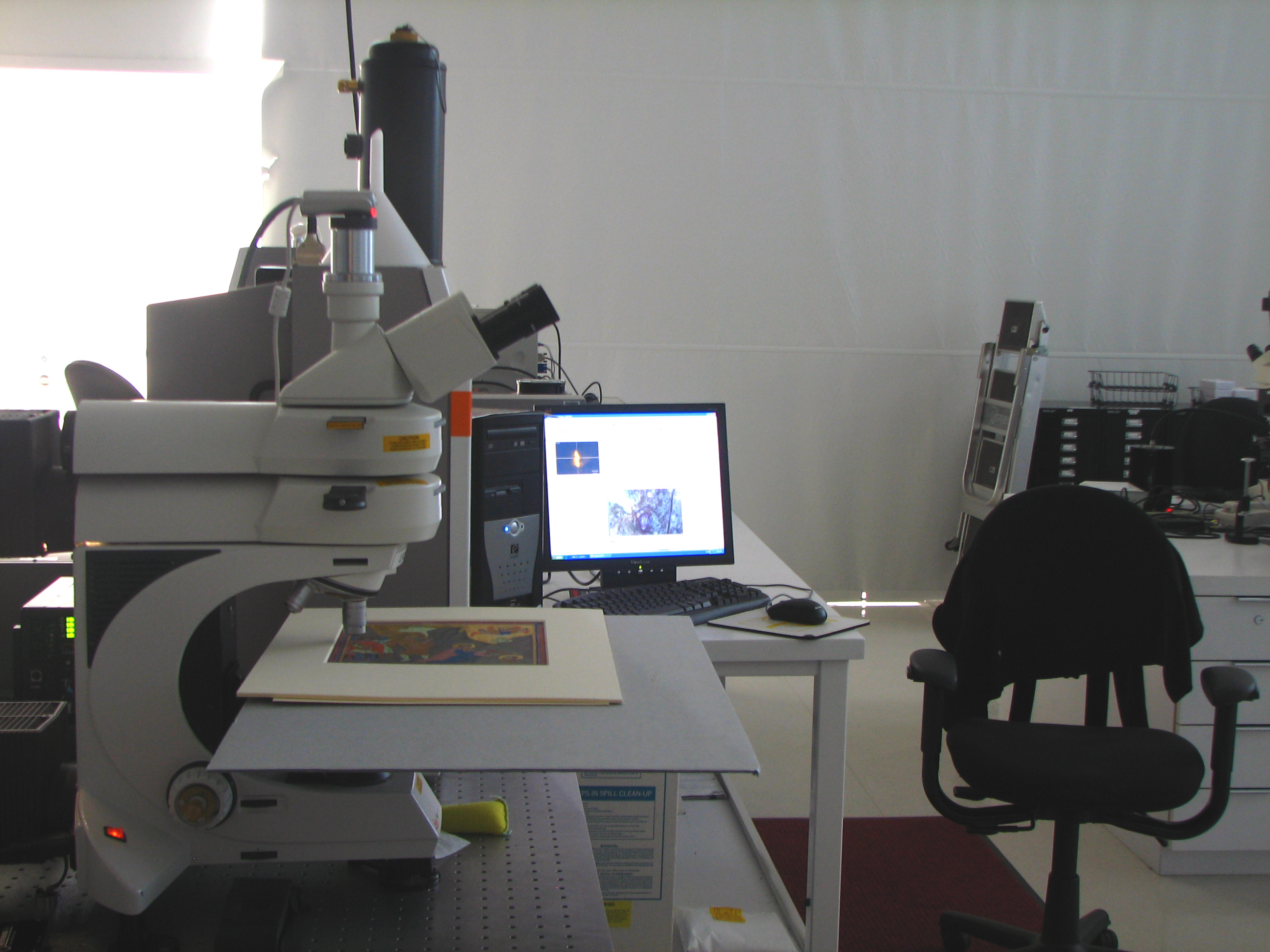

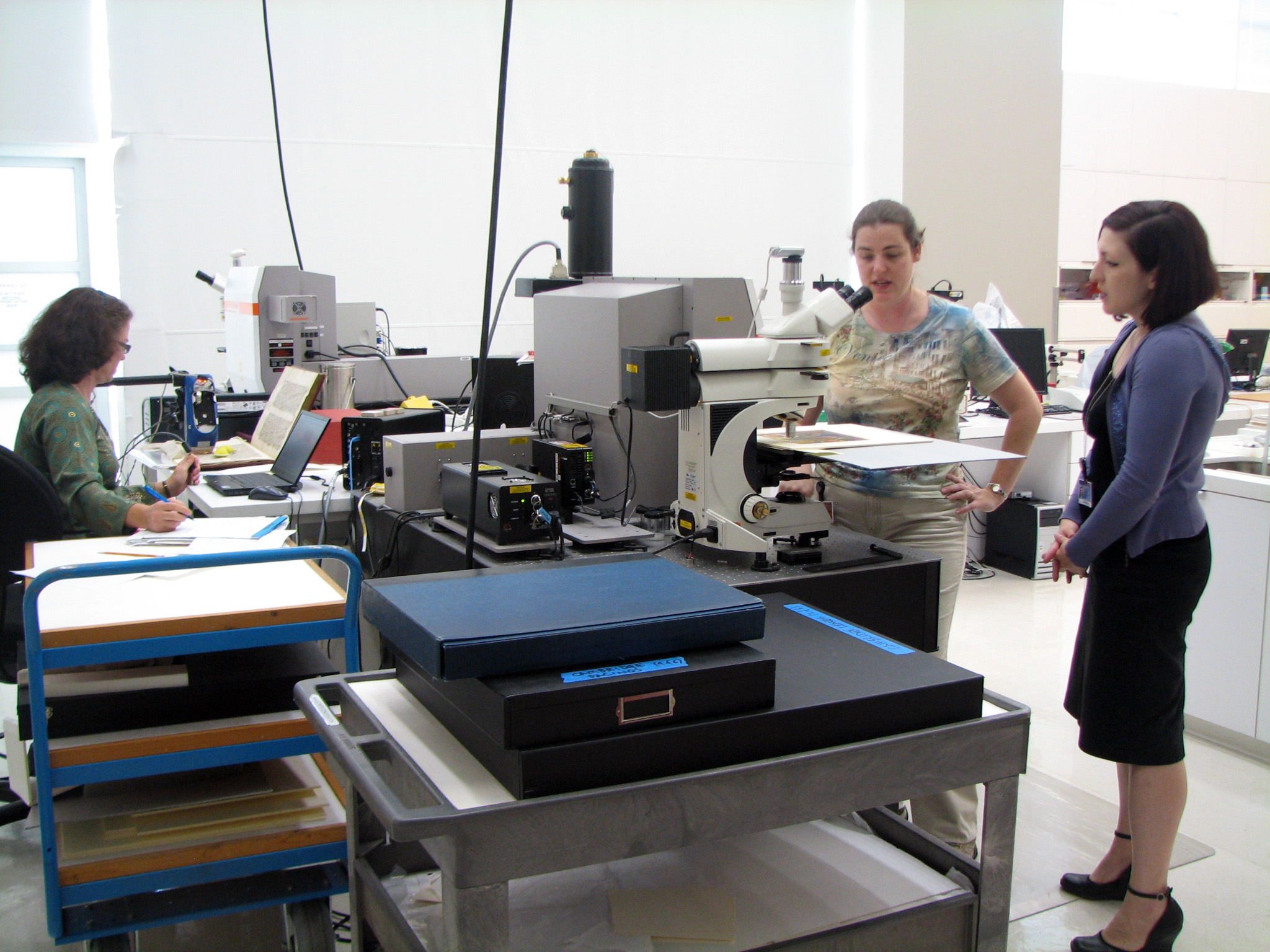

Plans were made for me to accompany the miniatures to Los Angeles in summer 2009 and review the analytical procedures. The arrangements took the College into new realms of legal discussion, as insurance agreements between us and the Getty had to take account of many risks, including the potential for ownership disputes. At this stage, the lack of provenance data for the cuttings’ arrival in Queens’ presented something of a problem, and conjured visions ranging from straightforward theft to claims of Nazi seizure. Fortunately, however, records confirmed their presence in College far enough back to dim this risk. It is worth noting though, that such unattributed acquisitions, perhaps long forgotten gifts, may now be financially as well as historically valuable, and the importance of acquisition records cannot be overemphasized. As planned, in July last year I took the miniatures to the Getty Museum, a stunning hilltop campus of gardens, galleries and terraces that commands panoramic views of Los Angeles and the North Pacific Ocean. I was welcomed by the curators, conservators and scientists of the Getty Museum and Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), who showed me around their conservation studio and laboratories, and demonstrated the state of the art equipment that would be used in the analyses. Their main objective was to “identify, characterize and compare the painting materials and techniques used by Pacino and his workshop” [4], particularly as previous investigation of the three Getty owned leaves had suggested the involvement of more than one artist’s hand, perhaps using a slightly different palette. This new study would widen the range of images studied, allowing direct comparison of nine of the 24 known surviving miniatures, and held the potential to reveal much about workshop practice of the 1340s. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and Raman microspectroscopy would be used to identify pigments under drawings and techniques, without taking physical samples or touching document surfaces, and digital images would provide a visual record of findings. The Cambridge leaves returned to the UK in September 2009 and the research findings, some of which were presented at a National Gallery symposium last autumn, will soon be published. The techniques used can be seen in the images below, which have been reproduced with kind permission of the GCI. |

||

|

|

||

Figure 5. Image of the Raman setup for laser light excitation; the manuscript under analysis is Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 194. Image reproduced with kind permission of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. This image gives another view of the Raman spectroscopy setup, using 785nm laser light excitation. The manuscript is mounted on an easel, and the light is guided through the microscope and onto the leaf through the black arm. The entire configuration is non-contact. |

||

Figure 7. Another image of the Raman setup for laser light excitation; the manuscript under analysis is, again, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 194. Image reproduced with kind permission of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. This image provides a close-up Raman image of MS 194, showing the laser spot as a yellow dot on the manuscript. Much more is expected to emerge from this collaboration between several quite different institutions. In addition to the publications in preparation, we look forward to taking part in the 2012 exhibition, for which the Cambridge miniatures will once again travel to Los Angeles. Meanwhile, the three Queens’ College Pacinos will soon relinquish their plan chest for a new home in the Founder’s Library at the Fitzwilliam Museum. The generosity of a number of College alumnae has enabled Queens’ to offer them on long term loan to the Museum, where they will be accessible to scholars and available for public display in a way which is not possible in the College Library. The Fitzwilliam will be able to store them with their own Pacino leaves in an environment that celebrates their significance and beauty as early Renaissance works of art. |

||

Notes

[1] Nigel Morgan and Stella Panayotova, A Catalogue of Western Book Illumination in the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Cambridge Colleges. Part 1, Vol.1. Harvey Miller Publishers, London 2009.

[2] Stella Panayotova, ‘New Miniatures by Pacino di Bonaguida in Cambridge’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. CLI, n. 1272, March 2009, pp. 144-147.

[3] R. Offner, A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century, Section 111, vol. VII, New York 1957.

[4] Unpublished Proposal for the Technical Analysis of Queens’ College, Cambridge MSS 77B, 77C, and 77D , submitted to Queens’ College by the J. Paul Getty Museum, March 2009.

On Euston Road, outside St Pancras station, a very small metal plaque on the pavement caught my eye. It said something like ‘legible london: visit the tfl [Transport for London] website’. What is this ‘legible london’ and how is it connected to transport, I wondered, and on arrival at the British Library did as the sign on the pavement told me and looked up this website:

http://www.tfl.gov.uk/microsites/legible-london/default.aspx

Legible London is an initiative to encourage the novel practice of… walking. The government has realised that many people do not walk around this city. We tend to use public transport all the time, especially the London Underground system, when often it would actually be quicker, healthier, more environmentally friendly, and free, to walk.

The website explains that ‘Based on extensive research, the system uses a range of information, including street signs and printed maps, to help people find their way.’ At first I was surprised and somewhat sceptical to read that ‘extensive research’ was undertaken to produce the necessary material texts – signs and maps – which we surely ought take for granted as visible and legible in any urban space, particularly a capital city.

However, the ‘Maps and Signs’ section of the website explains the project in more detail. The material features of the new signs and maps have been thought about very carefully, to encourage a more intuitive interaction with the cityscape. Although I found the tone of the website a little patronising, I was interested by the explanations of how the size, shape, orientation, colour, and positioning of the new maps and signs have been designed to make it easier to connect the meaning of these material texts with the environment and the routes we want to trace through it. On public transport we are moved passively around the city (particularly in the darkness of the Underground, where we literally cannot see or read the landscape). The Legible London initiative puts a spotlight on the importance of the material text in the context of changing realisations about urban travel, something essential for almost everyone, every day, everywhere.

Several CMT bags and their owners will be journeying north of the border this week for the ‘Material Cultures 2010’ conference hosted by the Centre for the History of the Book at the University of Edinburgh. The three-day programme, viewable here, features keynote papers by Roger Chartier, Jerome McGann, and Peter Stallybrass. Delegates will be spoilt for choice during the panel sessions, which promise material and textual delights from nineteenth-century fashion magazines and Algonquin words to blogs and Scottish manuscript miscellanies. Expect reports here afterwards!