… to Charlotte Panofré, a postgraduate member of the Centre, who has received this year’s Sir John Neale Prize in sixteenth-century history. Charlotte’s article on the publishing activities of the Marian exile community in Geneva won the prestigious £1500 award, which is administered by the Institute of Historical Research at the University of London. Another CMT member, Dunstan Roberts, was joint-winner in 2008 for his essay analysing anonymous marginalia in a copy of ‘The Institution of a Christen Man’. The success of these students, both based in the Cambridge English Faculty, is testimony to the way that work on the material text can win assent across the usual disciplinary boundaries.

The major spring/summer exhibition at the Victoria and Albert museum this year is ‘Quilts 1700-2010’. This exhibition showcases over 60 British quilts from the V and A collection with others loaned from museums and galleries in the UK and beyond. Displayed alongside these historical exhibits are some striking quilts made by contemporary artists including Tracey Emin and Grayson Perry. I would love to include some photographs in this post, but they appear difficult to find online. Have a look at the BBC’s special audio slideshow for a glimpse of some of them.

The exhibition is arranged around five themes: ‘The Domestic Landscape’, ‘Virtue and Virtuosity’, ‘Meeting the Past’, ‘Making a Living’, and ‘Private Thoughts – Political Debates’. A message that is both implicitly and explicitly communicated throughout is that these handmade domestic objects hold stories and histories in their very fibres. They are understood as texts as well as textiles. The curators have consciously probed the ways in which quilts can ‘document love, marriage, births, deaths, periods of intense patriotic fervour, regional and national identity and developments in taste and fashion’, reminding us also in the printed exhibition guide that quilts are ‘repositories of memory’, ‘acts of remembrance’, and ‘a form of meditation and consolation’.

While much of the beauty and interest of these objects lies in the colours, prints, patterns, and textures of the intricately pieced fabrics, often their makers added words too – names, dates, biblical verses, and short poems, for example. Indeed, many of the quilts demonstrate an explicit engagement with the power of visible text. Several commemorate coronations and military victories. On others, short sentences and poems emphasise the value of hard work and perseverance embodied in the material in which we read them, and on others, they provide spiritual advice and comfort. On a quilt made for a nineteenth-century military hospital, for example, verses from scripture appear on all four edges, so that they could be read by patients in neighbouring beds as well as by the person lying under the quilt.

One of the most moving exhibits for me was the quilt made last year by inmates of Wandsworth prison. The impressive craftsmanship of the panels on this quilt belies the hands that made them – those of male prisoners who had previously had little experience of what is traditionally seen as a domestic and feminine activity. On their quilt we read a collection of embroidered messages that are witty, entertaining, angry, disturbing, and sad. For these men, the quilt became a communal site for expression in words and pictures; the materials and methods of quilt-making provide the opportunity for communication with language via a creative engagement with materials. Compare this with the Rajah quilt, made in 1841 by women convicts onboard HMS Rajah as they were being transported to lands in the south Pacific. The tools and materials they used were supplied by Elizabeth Fry’s social reform project, and the words embroidered in a central panel on the quilt express the gratitude of the quilt’s makers for the creative opportunities this charity gave them during their long voyage.

Of all the quilts in the exhibition, Sara Impey’s recent ‘Punctuation’ quilt explores most explicitly a relationship between text and textile. Each tiny panel of her quilt is an embroidered letter, and together the panels play with phrases taken from a love letter to Impey’s mother that was discovered after her mother’s death. You can see images of similar works by Impey here. In this very consciously material text, Impey explores the popular idea that love letters were traditionally cut up to make the paper templates needed for piecing a quilt. The traditional materiality of the patchwork quilt becomes a medium through which to make sense from textual and material fragments, to re-read the past and to contextualise a fragmentary piece of documentary evidence from her mother’s life.

The juxtaposition of quilts such as this one with others made as many as three hundred years ago illustrates how the quilt continues to be a site of personal or political protest, debate, and subversion. While every quilt has its own story, some quilts stress their message in visible textual ways, inviting us to read them as we might read other kinds of material texts.

Sue Pritchard, curator of contemporary textiles at the V and A, writes a blog in which she explores many of the quilts in more detail. ‘Quilts 1700-2010’ runs until for ten more days, until 4 July.

A painful story. A couple of weeks ago I was invited to take part in a workshop at the Victoria and Albert Museum, drawing on the expertise of staff and students on the V&A/RCA MA in the History of Design. I had pre-circulated an early modern inventory that is central to my current research, and at the start of the workshop I sent round a few pages of a diary/account-book that is another of my key sources. The discussion went quickly in a very intelligent and not entirely unforeseeable direction. Who (I was asked) was supposed to be reading this account book? How was it bound, and what did the binding materials imply about its status? Was this a pre-bound volume into which entries had been written, or a pile of paper that had been bound up after the event? Embarrassed, I had to confess: I hadn’t actually seen this manuscript. I was in Cambridge; the manuscript was in Washington. Obviously, during the course of my research I *would* get my hands on it and answer those important questions, but the time had not yet come.

This was a curious moment for me, partly because it seemed so bizarre (how could I, who had written a whole book about the importance of books as artefacts, have fallen into this trap?) and partly because it made me feel insufficiently jet-setting (other academics in my field must be flying over to Washington once or twice a year, and dropping into the Folger on a whim). But if I’m honest, my motives for not having yet visited my manuscript are partly ecological–I don’t want to cross the Atlantic again until I have a need sufficient to justify (however thinly) my flight. To some, such agonizing will seem absurd, and they should stop reading now. Others may see that there’s a problem here, a problem which is in any case separable from the environmental concern. (How) can we work on a material text when we can’t actually get to it?

One kind of answer to this question might come from the libraries. Our great research libraries enjoy welcoming scholars from overseas, but they could start thinking of more ways to keep them at bay, or to provide a greater range of academic services at a distance. They could offer cheap, watermarked digital images for research purposes, for example, so that the physical properties of the book can be gauged and interpreted; or they could employ in-house bibliographers to answer detailed enquiries about books (including, say, transcriptions of marginalia). Or they could maintain a register of affiliated scholars who would be willing to act as proxies in the investigation of material aspects of a text (for a small fee, or on a tit-for-tat basis). But libraries have a lot on their plates already. We academics could be advertising our research services for ourselves. Is there, somewhere out there on the web, a bulletin board for this purpose?

It’s true, of course, that nothing can substitute for personal engagement with the real thing, and I shall certainly be going to Washington at some point in the near future. But if there’s an early modernist sitting in the Folger who wants to swap an hour or two of research time with me in Cambridge, please drop me a line (jes1003@cam.ac.uk). Who knows, it could be the start of something…

http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2010/may/21/children-do-not-write-letters

This short article was published in The Guardian a couple of weeks ago, but I’ve only just come across it. According to a survey by World Vision, one in five children today have never received a handwritten letter, and about one in four children have never written one themselves. Erasmus would surely be horrified at this symptom of the quick-fix lives we lead in the rich developed world of the twenty-first century. The education expert Sue Palmer (of ‘Toxic Childhood’ fame) offers some wisdom in this piece, although is she right to claim that ‘literacy is the hallmark of human civilisation’? (Answers on a handwritten postcard…)

Palmer’s view of literacy is a limited one – apparently emails and text messages are not evidence of literacy. She emphasises the importance of the physical effort involved in writing a letter by hand, and the pleasure of receiving a material text that can be treasured as an object. I don’t think we can disagree with her on this. True ‘literacy’, then, is firmly grounded in visible, tangible materials of writing and reading. Is this a fair and realistic expectation today, and can we really, like Palmer, relegate less tangible forms of communication to some other category?

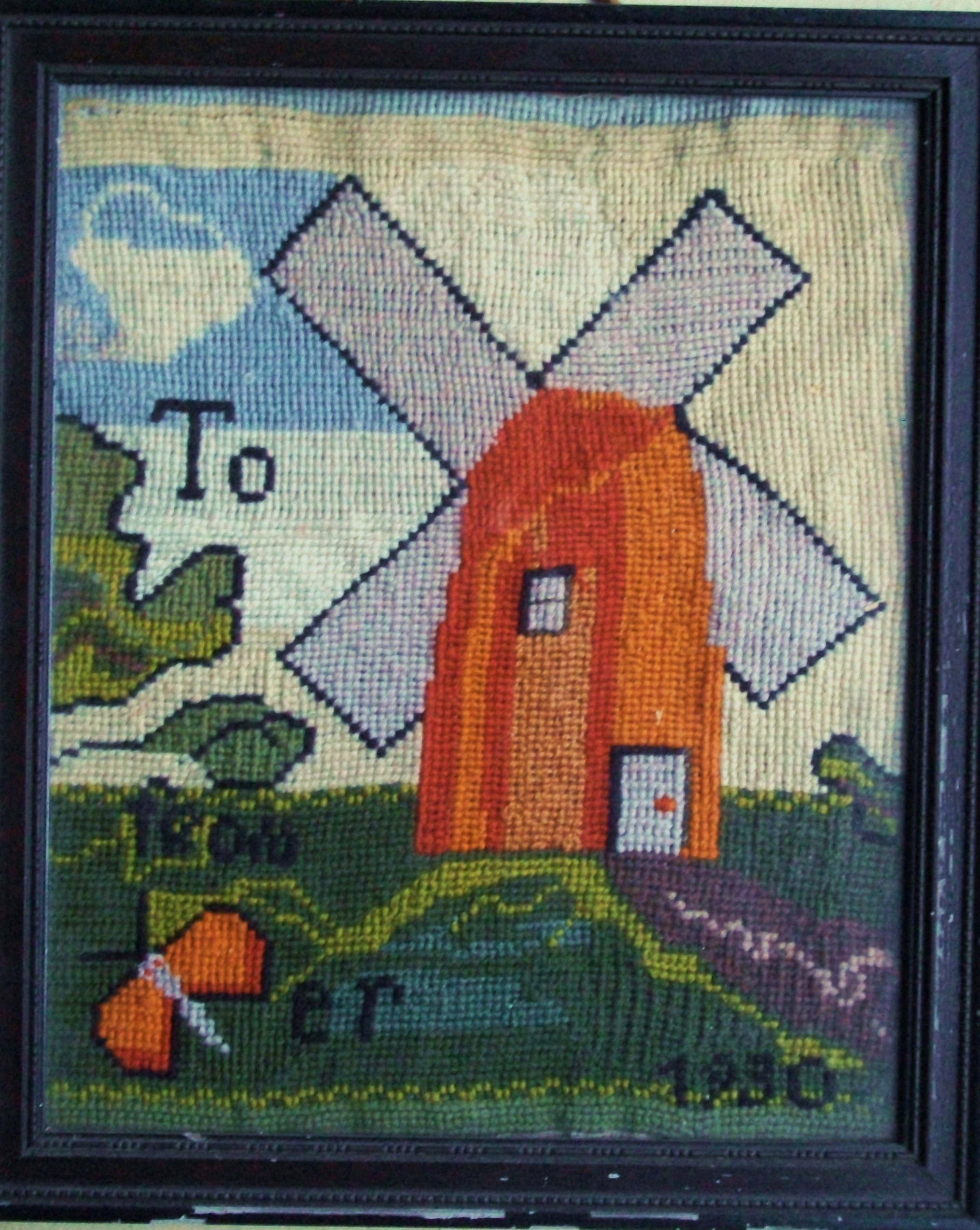

Everyone is working very hard in Cambridge at the moment, especially those marking exam scripts. Here’s a more colourful image of industry and creative inspiration – a touching gift worked by a mother for her daughter, whose name we ‘read’ in the windmill.

The scene is quite crudely executed – the sails of the windmill are not at all symmetrical – but we can also see how this text is an inspired and very resourceful piece of work. The whole scene is worked with different scraps of tapestry yarn which don’t quite match, suggesting that the maker possessed limited supplies and simply worked with what materials she had. It speaks of a climate of austerity and ‘making-do’ that we no longer really know, and is a charming illustration of practicality and imagination employed in the making of a personal gift for a loved one, perhaps in restricted financial circumstances.

(Many thanks to my own mother, to whom this framed tapestry belongs. She found it on a market stall some years ago.)

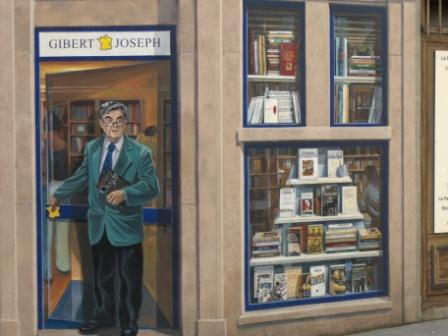

There are many wonderful things to see in Lyon, a city with a vibrant history stretching back thousands of years. Some elements of this history are explored on the distinctive ‘murs peints’ which can be found all over the city. There are over one hundred of these painted walls; impressive works of trompe l’oeil which cover the sides of buildings. I stumbled across the one above, the ‘Fresque des Lyonnais’, which features significant figures from throughout 2,000 years of the city’s history, including Auguste and Louis Lumière, and Antoine de St-Exupéry. Individuals from different centuries converse with each other at windows and balconies, reminding us of the city’s rich creative heritage. In the lower left-hand corner of this wall, there is a painted bookshop…

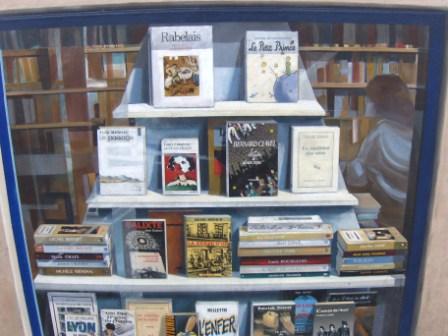

And here are some of the books for sale, displayed in the window to tempt us inside…

The book titles and names of authors we see here are familiar, but the painted images themselves also play with our sense of reality. These books look tantalisingly real, but the painter reminds us with a few subtle brush strokes that not only are we separated from them by a window, but that the ‘window’ itself is only painted. I was reminded a little of the painted walls of the host’s house in Erasmus’s The Godly Feast. Although the walls in Lyon are not the morally improving images from scripture that cover the walls of Eusebius’s house and garden, they still provoke a similar speculation and wonder at the skill of the painter who renders people and things so life-like that it is as if we could reach out and touch them. Upon seeing the painted walls, one of the guests in Erasmus’s text exclaims ‘Who could be bored in this house?’ In Lyon, it is more a question of ‘Who could be bored in this city?’

I came across this doorway in a quiet back street of Lyon last summer. The words engraved above the date on the stone door frame are taken from Cicero:

‘The truth is, a man’s dignity may be enhanced by the house he lives in, but not wholly secured by it; the owner should bring honour to his house, not the house to its owner’

(De Officiis, 1.138-9, Walter Miller’s Loeb translation).

A man’s honourable character makes his house truly dignified, not the other way round. Engraved above the entrance to a building, this proverbial message is literally embedded in the matter and material about which it speaks.

This photograph presents us with a more elaborate material text, however. Cicero’s moralising words about the relationship between a man and his house, engraved by a seventeenth-century stonemason, are juxtaposed with the spray-can marks of contemporary graffiti. The multicoloured graffiti tags covering the door contrast with the delicate swirl motifs which ornament the letters in the stone above. The wooden door has become a public writing surface which invites the addition of more and more text, the presence of which, convention decrees, is an unauthorized defacement of the door, a dishonouring of private property.

As Juliet Fleming reminds in her landmark volume on early modern graffiti, the media with which graffiti are created usually means that their long-term survival is unlikely. Unlike the engraved motto on this door, which has so far survived for over three hundred years (and whose literary origin takes us back over two thousand years) the graffiti here are temporary, fleeting, and we can see where they have faded or been scrubbed away.

Fleming also reminds us it is ‘the visible placement of modern graffiti that constitutes its scandal as a form of writing that, exceptionally, is understood to be filling space’ (Graffiti and the Writing Arts of Early Modern England, pp. 33-4). We may not ‘read’ this modern graffiti in the same way that we read the seventeenth-century motto here, but this striking juxtaposition of distinctively early modern and modern forms of text in a very public space illustrates the different moral and aesthetic questions raised as writing negotiates its place in the material around us.

History of Material Texts Seminar Series

History of Material Texts Seminar Series

Thursday 27 May 2010, 5.30 p.m.

Subha Mukherji (Downing) will speak on ‘The voice of things: some archival evidence’, and Christopher Burlinson (Jesus) on ‘Maps and letters in the early modern archive’.

Room SR-24 in the Faculty of English, 9 West Road, Cambridge.

All welcome. For further details, contact Daniel Wakelin (dlw22@cam.ac.uk) or Sarah Cain (stc22@cam.ac.uk). .

This week sees the broadcasting on BBC Radio 4 of the second part of ‘A History of the World in 100 Objects’, a collaboration between the BBC and the British Museum. Over the next eight weeks Neil MacGregor, the British Museum’s Director, will cover 1800 years of history from 300 BC to 1500 AD, as he explores another group of objects from the Museum’s collection.

The online presence of the project is key to the accessibility of the objects. There are short videos about some of the objects, and the 100 radio broadcasts can be downloaded as podcasts. The high quality photographs in the online gallery allow close inspection of each object. Furthermore, other institutions and individuals can participate with their own objects. Already over 350 museums across the UK have registered with 100 objects from their collections, and members of the public can also record details of their own objects online.

I have been thinking about the handful of objects from the 100 chosen from the British Museum’s huge collection which present us with ‘text’. The surfaces of some of the objects are decorated with pictorial representations; the illustrations on the mysterious Standard of Ur, for example, give us scenes of war in Mesopotamia over 4000 years ago. Hieroglyphs on an ivory sandal label found in the tomb of the Egyptian King Den (c. 2985 BC) celebrate the wearer’s military conquests. There are wall painting fragments, masks, sculptures, carved reliefs, and statues, all of which present us with anthropomorphic representations. Not so many of the objects actually feature writing, however.

The objects which do display text include a famous cuneiform tablet from Assyria (700-600 BC) telling the story of a great flood, which was sensationally compared with the Biblical flood when it was first translated in 1872; an Indus seal bearing some of the oldest writing from South Asia, as yet undeciphered; an early writing tablet from Mesopotamia; and an Egyptian mathematical papyrus. There is writing which plays with the aesthetic potential of ink on paper, as in the Tughra of Süleyman the Magnificent, and there are mathematical and scientific instruments which combine words and numbers. Text can be found on several maps, on Dürer’s woodcut print of an Indian rhinoceros, and on a broadsheet marking the centenary of the Reformation in Germany. Forms of money emerge as significant textual objects across thousands of years: there are five coins including a coin with the head of Alexander and a penny defaced by Suffragettes, a Ming banknote, and the newest of the 100 objects, a credit card.

In these objects, writing is found on flat surfaces and three-dimensional forms. It is found on the inside and outside of objects. It is carved, engraved, embossed, handwritten, stamped, and printed, and tells us about changing technologies of the word. Many different languages, ages, and civilisations are represented, and the writing on these objects serves many different rhetorical functions too. The 100 British Museum objects, as well as all of the other objects registered on the website, can be sorted and compared by themes, including ‘Food’, ‘Travel’, ‘Protest’, ‘Body’, ‘Clothing’, and ‘War’. I would like to suggest another theme: ‘Text’. What could we learn by comparing all of the objects which feature writing in some form? In each example, how does the writing relate to the object? How do the specific materialities of these objects shape and inform their function as texts? Should we think about these objects differently from the objects without any text?

PS: The 100th object is still a mystery: its identity will be revealed in the Autumn. Any guesses?

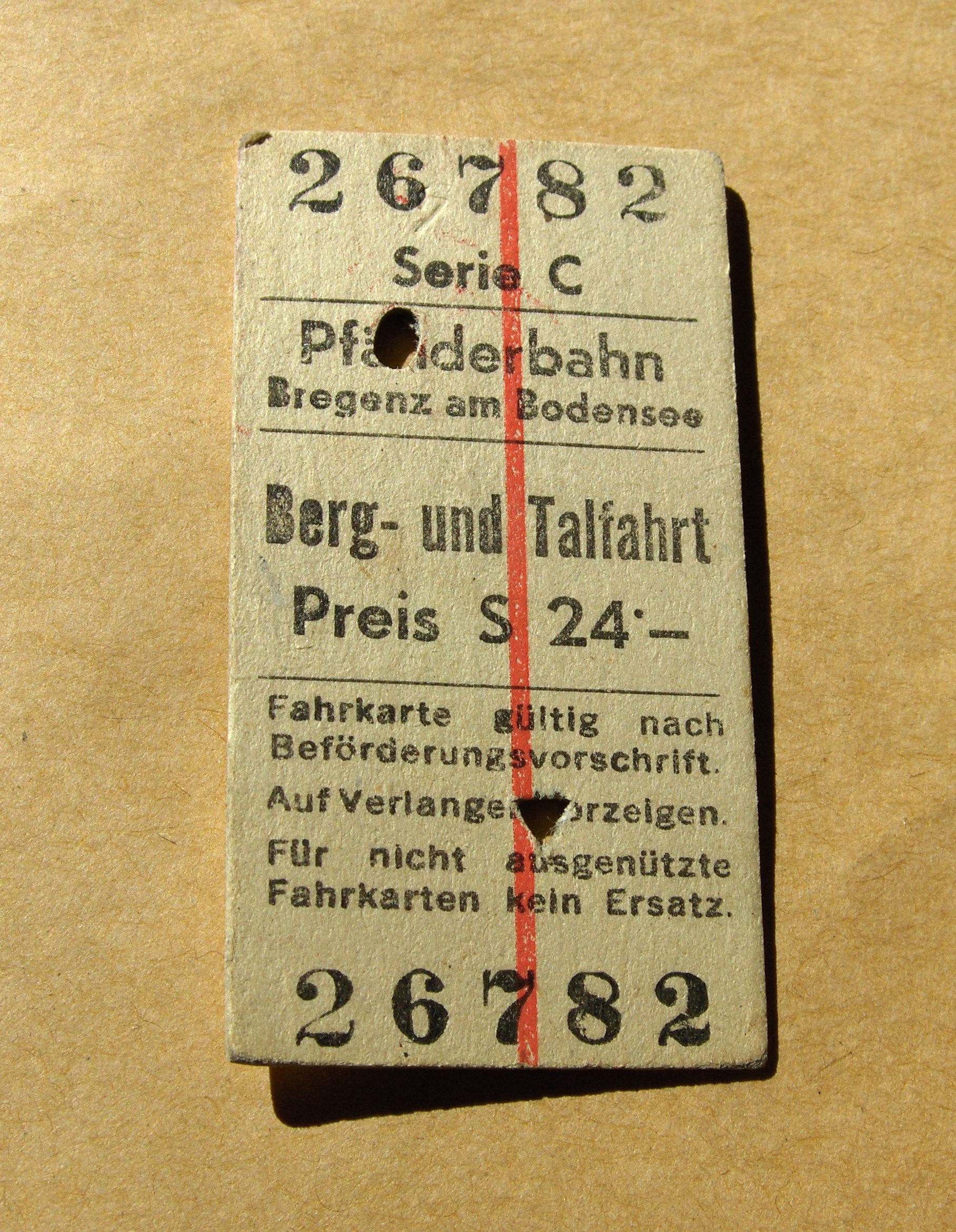

Ticket valid after being stamped. To be shown on demand. No refund for unused tickets.

May 14th, 2010Blog; Lucy RazzallI recently bought a smart but very old suede handbag, second-hand. The clever design of the bag embraces its function as an object of both practicality and of aesthetic value. I was also attracted to it because of the information on the label – made in the small town of Pitlochry in the heart of Scotland, this accessory is a beautiful example of British craftsmanship, regrettably an increasingly rare phenomenon in our age of cheap imported goods made by exploited factory workers in China and Eastern Europe.

Inside the zipped pocket of this bag, I was pleasantly surprised to discover a tiny material text. It is a return ticket, printed on stiff card and measuring approximately 1×2 inches, for a mountain cable car in Austria. The ticket bears no date, but the price (24 schillings) is a clue to how old it might be – several decades, at the very least. The two holes suggest that the holder of this ticket successfully validated their ticket and made it up and down the mountain. Ephemeral texts like this one are all around us, and ironically it is often such small and disposable material texts as travel tickets, till receipts, and shopping lists, that slip through gaps or are stuffed without a second thought into pockets, and survive by being forgotten, to be discovered unexpectedly at times and places in the indeterminate future.

This particular ticket connects us to a specific tourist attraction (the Pfänderbahn above Lake Constance still exists, by the way, current price ten euros and eighty cents for an Adult return ticket), but what is most interesting about it as a material text is the unwritten story behind its survival and discovery in the personal space of a handbag. The unearthing of such ephemeral texts traces faint but tantalising connections between people and places, inviting us to imagine the journeys a text, no matter how small, has taken to reach us.

I am writing here as a graduate student guest blogger. Over the next few weeks I will be contributing more thoughts and reflections on material texts, not all of them as small or ephemeral as this one!