Credit: Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadephia

Scholars believe that they have identified John Milton’s copy of the First Folio of Shakespeare.

This copy of the first large-format (folio) edition of Shakespeare’s plays, published in 1623, has been housed in the Free Library of Philadelphia since 1944, when it was donated to the library by the Widener family. It has been known to scholars since 1899, when Sidney Lee first analysed the volume. The Free Library’s copy has long been recognised as ‘one of the finest in existence’ and as containing ‘17th century MS. notes of value’.

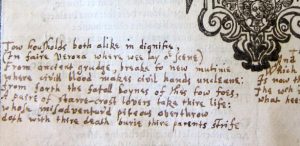

In a recent re-examination of the volume, Claire M. L. Bourne, Assistant Professor of English at Pennsylvania State University, observed that the manuscript notes in two of the plays in the Folio, Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet, showed that the anonymous reader was comparing the text of 1623 with small-format (quarto) editions of the plays, one of which was published in 1637. The reader uses the quartos to suggest corrections and improvements where the folio text appears to be faulty, showing an awareness that a number of different versions of Shakespeare’s plays were circulating in print. In addition, this reader supplies additional material (eg the prologue to Romeo and Juliet, which is absent from the folio), supplies cross-references to other works, and sometimes corrects the text using inspired guesswork. Bourne’s study revealed that the annotations were penned by an unusually subtle reader who ‘was attentive to the sense, accuracy, and interpretative possibility of the dialogue’. Bourne also consolidated the claim that the notes date from the mid-seventeenth century, and provided copious illustrations of the handwritten interventions.

On reading Bourne’s article, Jason Scott-Warren, Reader in Early Modern Literature and Culture at the University of Cambridge, and Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, was struck by the similarity of the handwriting in the folio to that of the poet John Milton (1608-1674). A comparison of the details supplied by Bourne with Milton’s surviving manuscript drafts and with his corrections in other books suggested that the identification might be correct, and the claim has subsequently been backed up by a number of experts in this field. One feature of Milton’s hand is that it changes significantly over time—for example, he starts writing a modern ‘e’ rather than ‘ε’ when he returns from a trip to Italy in 1639. On this basis, it seems likely that some of the annotations date from before 1639 and some from after that date. The detailed editorial work that the reader did to improve the text of the folio is consistent with Milton’s practice in other books that survive from his library, including his copy of Boccaccio’s Life of Dante. Apart from his family Bible, this is the first vernacular book to resurface from Milton’s library, from which only 9 titles have hitherto been identified.

With the identification of Milton as the annotator of this copy, detailed attention will need to be paid to the copious non-verbal marks it contains, which are present to some extent in all but four of the plays in the volume, and which show a particularly sustained engagement not just with Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet, but also with Macbeth, The Tempest, Henry IV, As You Like It and King Lear. An initial survey suggests that many of the preoccupations of his prodigious literary career can be traced in his reading. Milton expressed his ‘wonder and astonishment’ at the writer he called ‘my Shakespeare’ in an epitaph that was printed in the second folio of the plays in 1632, and he was influenced by Shakespeare throughout his literary career. Apart from his family Bible, this is the first vernacular book to resurface from Milton’s library, from which only 8 titles have hitherto been identified.

Shakespeare’s first folio of 1623 is widely acknowledged to be one of the most significant books ever published. It contained 36 plays, only 18 of which had been previously published; without it, many of Shakespeare’s best-known plays would probably have been lost forever. It is now one of the most expensive books in the world, despite the fact that is not especially rare (more than 230 copies are known to survive). The volume is famous for its complex printing history. No two copies of the printed text are identical, and surviving copies have all been marked in different ways by the hands they have passed through. Few, however, have as distinguished a provenance as the copy identified here.

TESTIMONIALS

Two quotations from Dr Will Poole, John Galsworthy Fellow and Tutor in English at New College Oxford:

“Not only does this hand look like Milton’s, but it behaves like Milton’s writing elsewhere does, doing exactly the things Milton does when he annotates books, and using exactly the same marks.”

“Shakespeare is our most famous writer, and the poet John Milton was his most famous younger contemporary. It was, until a few days ago, simply too much to hope that Milton’s own copy of Shakespeare might have survived — and yet the evidence here so far is persuasive. This may be one of the most important literary discoveries of modern times.”

REFERENCES

Claire M. L. Bourne, ‘Vide Supplementum: Early Modern Collation as Play-Reading in the First Folio’, in Kathy Acheson, ed., Early Modern English Marginalia (London: Routledge, 2019).

‘WITH(OUT) MILTON: DATING THE ANNOTATIONS IN THE FREE LIBRARY OF PHILADELPHIA’S FIRST FOLIO’, https://www.ofpilcrows.com/blog/2019/9/12/flp-folio-without-milton

William Poole, ‘John Milton and Giovanni Boccaccio’s Vita di Dante’, Milton Quarterly 48 (2014), 139-70.

Jason Scott-Warren, ‘Milton’s Shakespeare’, https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/cmt/?page_id=574