ALONSO What harmony is this? My good friends, hark!

GONZALO Marvellous sweet music!

ALONSO Give us kind keepers, heavens! What were these?

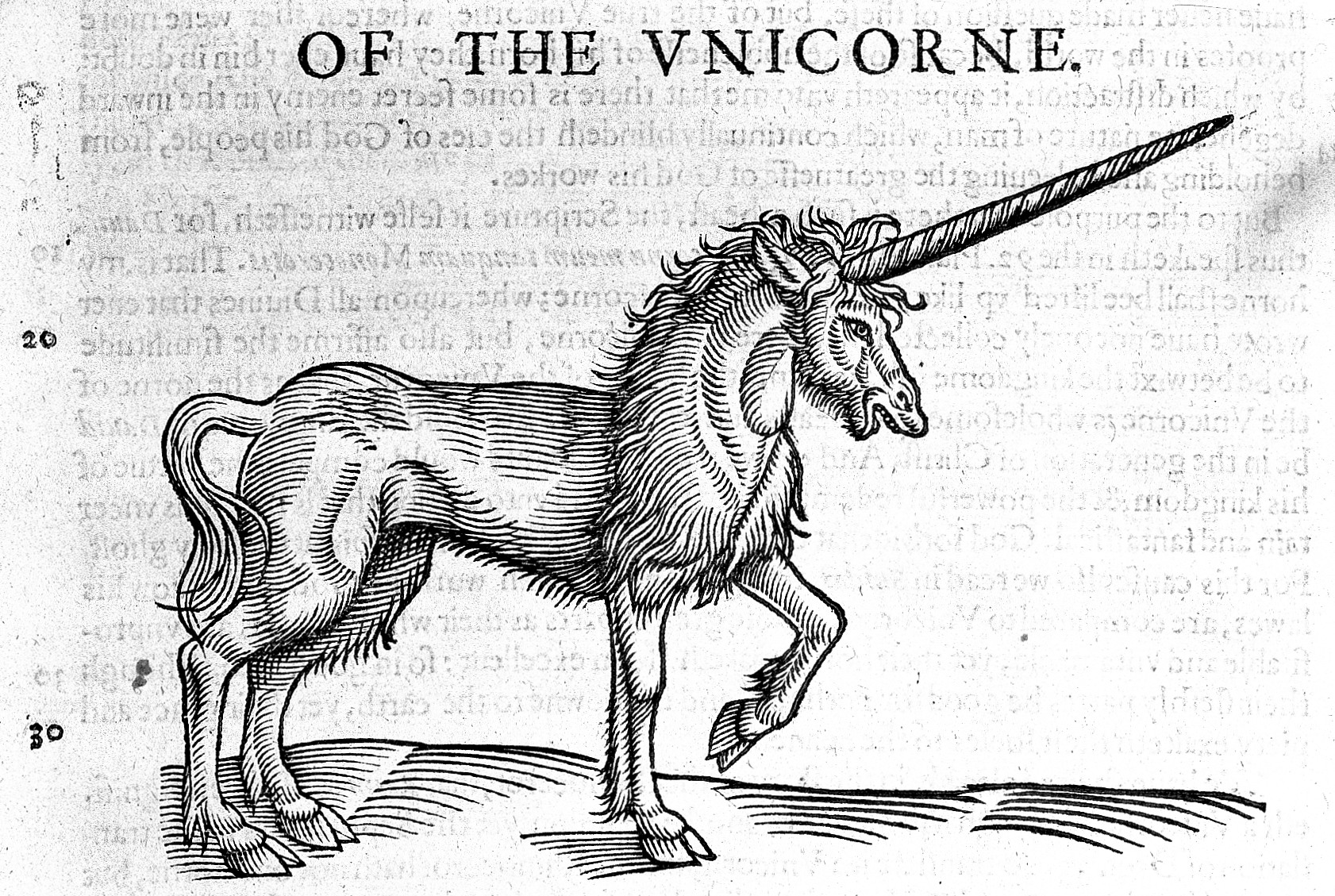

SEBASTIAN A living drollery! Now I will believe

That there are unicorns; that in Arabia

There is one tree, the phoenix’ throne, one phoenix

At this hour reigning there.

ANTONIO I’ll believe both;

And what does else want credit, come to me

And I’ll be sworn ’tis true. Travellers ne’er did lie,

Though fools at home condemn ’em. (3.3.18-27)

There’s a certain irony in Alonso commenting on the harmony of the music, when (unbeknownst to him) his companions are planning murder and usurpation. The situation he’s in is not harmonious at all. But it’s an economical character note: the king, for all his grief and despair, is moved by the music, wanting to make sure that his good friends (ironic) can hear it too. In this respect he’s like his son Ferdinand, comforted by Ariel’s song in 1.2. We like Ferdinand. We’re coming to like Alonso more too, to feel sorry for him. Gonzalo is affected similarly to the king, hearing beauty and sweetness. What was that? asks Alonso. Who – or what – were these dancers, people, spirits? Give us kind keepers, heavens! Guardian angels, perhaps, or spirits to protect us. Alonso and Gonzalo are filled with wonder; they are not, it seems, especially afraid. Sebastian and Antonio, of course, are less awestruck, and they respond to the visual spectacle rather than to the music, interestingly. Sebastian calls it a living drollery, a puppet show performed by human actors (drollery suggesting that it is comic; he is determined not to be too impressed, perhaps). But he can’t help himself (or is he being ironic?): now I will believe that there are unicorns. (Many, if not most people would have believed in unicorns in 1611.) And in the phoenix too, the miraculous bird (only one at a time; self-immolating and re-generating) used as an avatar of beauty and uniqueness; it was adopted as such by Elizabeth I as one of her symbols. (In Cymbeline, Iachimo describes Innogen as ‘th’Arabian bird’, 1.6, referring to her beauty and apparent virtue.) The tree in which the phoenix nested was a palm-tree; she built her nest from cinnamon bark and cassia and other fragrant and exotic spices. I’ll believe in both of those, retorts Antonio, and anything else that usually wants, lacks credit, is seen as unbelievable. All travellers’ tales, usually regarded as exaggerated, fantastical, sheer invention, on this evidence, are true. Space is left for Antonio and Sebastian to be mocking; they are certainly not changed or especially moved. More fool them…

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Unicorn.

Woodcut

The historie of foure-footed beastes

Edward Topsell

Published: 1607

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/