PROSPERO Sir, I am vexed;

Bear with my weakness; my old brain is troubled.

Be not disturbed with my infirmity.

If you be pleased, retired into my cell

And there repose. A turn or two I’ll walk

To still my beating mind.

FERDINAND, MIRANDA We wish your peace. Exeunt.

PROSPERO Come with a thought, I thank thee, Ariel. Come! (4.1.158-164)

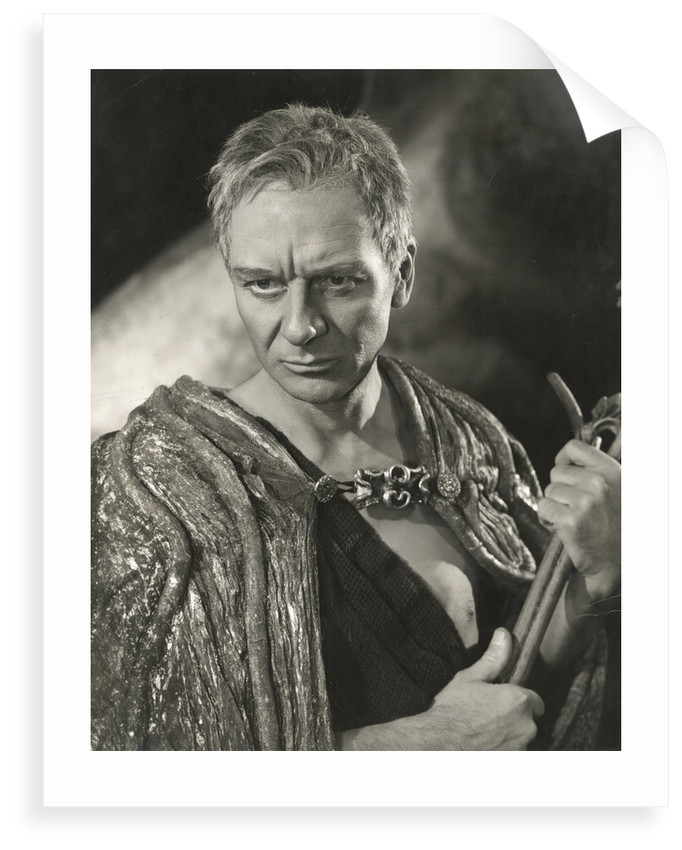

Prospero framed his speech as consolation and reassurance for Ferdinand and Miranda, but now he is more candid about his own needs, in this series of short, almost plaintive statements. (When Prospero is most vulnerable, he has a tendency to speak in this way – no longer the long, rolling phrases, but choppy clauses, often with mid-line breaks.) He is carefully courteous to the king’s son, his almost-son-in-law: Sir, I am vexed; I am, as you noticed, upset, worried, troubled. Please bear with me and be patient; my old brain is troubled. (Lear: ‘I am a very foolish, fond old man … I fear I am not in my perfect mind’. How old is Prospero? He doesn’t have to be an old man. Burbage was 43 in 1611; Shakespeare was 47. The idea that actors might be roughly the same age as the characters they play is a pretty recent assumption: John Gielgud first played Prospero in 1930 at the age of 26, and Lear when he was 27. Of course old here, as used by Prospero can mean old in a chronological sense, but it doesn’t have to, or not exclusively. It could be being used more in a sense of mild disparagement, my silly old brain. Prospero can be played – and has been – in late middle age.) He’s referring to mental and emotional distress in physical terms (my weakness, my infirmity) – and there is, of course, the possibility that he simply needs to say something to get rid of Ferdinand and Miranda, so that he can take action on the conspiracy. But he does seem upset, far more upset than Ferdinand and Miranda, and he needs peace and solitude – and Ariel. The phrase that resonates most, I think, is his need to walk a turn or two to still my beating mind. A heart beats, not a mind, first of all – but Prospero is a man for whom the relationship between heart and mind, passion and intellect, is fraught. We might think of a drum beating, or a bell tolling – an insistent, penetrating noise, and sensation, felt as much as heard. Too many thoughts, the bell in the brain. But also, perhaps, the beat of wings, as if the mind were a bird, needing to be calmed… Prospero, scholar, knows that a quiet walk will help. But most of all, he needs Ariel, who is in some respects an externalised version of his brain, his power, attuned to what he needs psychologically, more even than the loving, well-intentioned Ferdinand and Miranda. Come with a thought, I thank thee, Ariel. Come as swift as thought, but also with a kind of telepathy.

And Ferdinand and Miranda, puzzled (not least by being trusted, apparently, to go off by themselves to repose, rest, in Prospero’s cell, after all those earlier admonitions) but apparently reassured, exit. The next movement of the plot is about to be hurriedly put in motion, as all the strands of the story continue to converge.