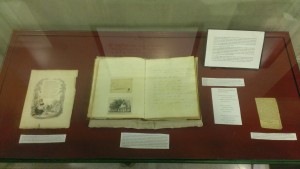

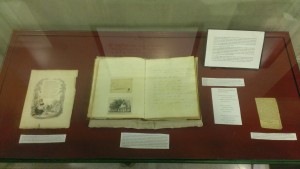

A backwater lay-by off the M5, Junction 24, three days before Christmas. A covert exchange of an unknown document, protected only by an iPad case, occurs between man, whippet and young woman. Shady as it may seem, this is not the stuff of reconnaissance but curation. This nineteenth-century commonplace book replete with beautiful illustrations, kindly donated by John and Caroline Robinson, now lies in situ on the first floor of the English Faculty, at the heart of the inaugural exhibition of the Centre for Material Texts. The exhibition, curated by myself and my MPhil colleagues on Dr Ruth Abbott’s Writers’ Notebooks course, focuses on commonplace books and the ways in which they acted as repositories for the recording of daily life in the nineteenth century. From passages of the Bible to Byron, musings on God to sketches of the family dogs, the commonplace book offered a powerful collective storehouse for the miscellanies and medleys of material that amassed at the center of communal family life.

A backwater lay-by off the M5, Junction 24, three days before Christmas. A covert exchange of an unknown document, protected only by an iPad case, occurs between man, whippet and young woman. Shady as it may seem, this is not the stuff of reconnaissance but curation. This nineteenth-century commonplace book replete with beautiful illustrations, kindly donated by John and Caroline Robinson, now lies in situ on the first floor of the English Faculty, at the heart of the inaugural exhibition of the Centre for Material Texts. The exhibition, curated by myself and my MPhil colleagues on Dr Ruth Abbott’s Writers’ Notebooks course, focuses on commonplace books and the ways in which they acted as repositories for the recording of daily life in the nineteenth century. From passages of the Bible to Byron, musings on God to sketches of the family dogs, the commonplace book offered a powerful collective storehouse for the miscellanies and medleys of material that amassed at the center of communal family life.

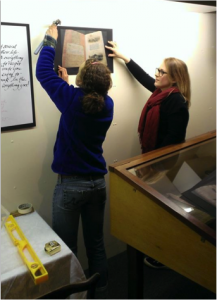

The unconventional method through which our exhibition materials were acquired proves apropos, given the unusual conditions under which the birth of our interest in commonplace books occurred. In another intrepid motorway adventure: a six hour, 250-mile minibus journey (nobly helmed by Ruth Abbott) with eight complete strangers, our group’s first weekend in Cambridge, was in fact spent in Grasmere, Cumbria working at the Wordsworth Trust. Guided by Ruth and curator Jeff Cowton we spent a full two days nestled in the archive, immersed in manuscripts and the materials which made them. It was a weekend stuffed with stuff. We created Thomas Bewick prints on a nineteenth-century printing press. We learned how to bind books on a sewing frame. Quills were carved and inks were made. Paste was pressed from pulp into paper (with the aid of a craftsman’s deckle and an improvised flattening dance on top of it). In a flurry of high spirits, fumbling with spirit-levels, our exhibition on the Wordsworth family commonplace books was installed.

The unconventional method through which our exhibition materials were acquired proves apropos, given the unusual conditions under which the birth of our interest in commonplace books occurred. In another intrepid motorway adventure: a six hour, 250-mile minibus journey (nobly helmed by Ruth Abbott) with eight complete strangers, our group’s first weekend in Cambridge, was in fact spent in Grasmere, Cumbria working at the Wordsworth Trust. Guided by Ruth and curator Jeff Cowton we spent a full two days nestled in the archive, immersed in manuscripts and the materials which made them. It was a weekend stuffed with stuff. We created Thomas Bewick prints on a nineteenth-century printing press. We learned how to bind books on a sewing frame. Quills were carved and inks were made. Paste was pressed from pulp into paper (with the aid of a craftsman’s deckle and an improvised flattening dance on top of it). In a flurry of high spirits, fumbling with spirit-levels, our exhibition on the Wordsworth family commonplace books was installed.

Like the chain lines and watermarks we spent the days studying in manuscripts, through curatorial collaboration we had impressed a profound mark on each other. The silence, sky and space of the Lakes and our collective academic endeavour had bound us together as tightly as the spines of the nineteenth-century treasures that lay on the archive’s shelves. What was particularly pertinent in creating this exhibition, born into being from deeply felt fellow-feeling from all parties, was that it chronicles and encourages the communal sharing of thought. The addition of our modern commonplace book to the display invites exhibition-goers to participate in shared forms of notetaking, to add their scraps and fragments of experience, their inmost thoughts, their favourite quotations and aid the creation of a beautiful, diverse collective text.

Like the chain lines and watermarks we spent the days studying in manuscripts, through curatorial collaboration we had impressed a profound mark on each other. The silence, sky and space of the Lakes and our collective academic endeavour had bound us together as tightly as the spines of the nineteenth-century treasures that lay on the archive’s shelves. What was particularly pertinent in creating this exhibition, born into being from deeply felt fellow-feeling from all parties, was that it chronicles and encourages the communal sharing of thought. The addition of our modern commonplace book to the display invites exhibition-goers to participate in shared forms of notetaking, to add their scraps and fragments of experience, their inmost thoughts, their favourite quotations and aid the creation of a beautiful, diverse collective text.

Speaking to other students who have visited Grasmere, at a recent meeting with the Wordsworth Trust at London’s Brigham Young Institute, I further realised the true powerful potential of the material. Through awe-filled eyes, each sentence suffused with a quasi-religious fervour, they recounted the moment they were allowed to see a first edition of Lyrical Ballads and handle Dorothy Wordsworth’s real notebooks. In fact, the Wordsworth Trust’s website proudly proclaims ‘Visit the Wordsworth Museum to see Dorothy’s actual notebooks’. This is something our group reflected upon as we sat around Wordsworth’s ‘actual’ fire in Dove Cottage, reading his poems, souls stirred by the transcendent beauty of breathing life back into words where they were first brought into being. In curating this exhibition, in Grasmere and in Cambridge, and through Ruth Abbott’s phenomenal notebooks course we have relearnt the overwhelming magic of the material, the ability to encounter and interact with the ‘actual’. It is in this kind of engagement with ‘actual’ manuscripts, notebooks and papers that ‘with an eye made quiet by the power/Of harmony, and the deep power of joy, / We see into the life of things’.

Speaking to other students who have visited Grasmere, at a recent meeting with the Wordsworth Trust at London’s Brigham Young Institute, I further realised the true powerful potential of the material. Through awe-filled eyes, each sentence suffused with a quasi-religious fervour, they recounted the moment they were allowed to see a first edition of Lyrical Ballads and handle Dorothy Wordsworth’s real notebooks. In fact, the Wordsworth Trust’s website proudly proclaims ‘Visit the Wordsworth Museum to see Dorothy’s actual notebooks’. This is something our group reflected upon as we sat around Wordsworth’s ‘actual’ fire in Dove Cottage, reading his poems, souls stirred by the transcendent beauty of breathing life back into words where they were first brought into being. In curating this exhibition, in Grasmere and in Cambridge, and through Ruth Abbott’s phenomenal notebooks course we have relearnt the overwhelming magic of the material, the ability to encounter and interact with the ‘actual’. It is in this kind of engagement with ‘actual’ manuscripts, notebooks and papers that ‘with an eye made quiet by the power/Of harmony, and the deep power of joy, / We see into the life of things’.

Through our immersion in the material practices from which texts develop, we learnt to cultivate a fresh appreciation for the ways in which literature is embodied and presented. The afterlives of the work we have done with these exhibitions, and the study of notebooks and manuscripts in general, like Wordsworth’s River Duddon, flow on endlessly. From future PhD projects to the reinstallation of the commonplace book exhibition in Cambridge ‘Still glides the Stream, and shall for ever glide;/The Form remains, the Function never dies’. We hope that in this latest reimagining of our display, we encourage others to see the beautiful potential in collective interaction with note-taking practices. In doing so, our work continues ‘to live, and act, and serve the future hour’.

Through our immersion in the material practices from which texts develop, we learnt to cultivate a fresh appreciation for the ways in which literature is embodied and presented. The afterlives of the work we have done with these exhibitions, and the study of notebooks and manuscripts in general, like Wordsworth’s River Duddon, flow on endlessly. From future PhD projects to the reinstallation of the commonplace book exhibition in Cambridge ‘Still glides the Stream, and shall for ever glide;/The Form remains, the Function never dies’. We hope that in this latest reimagining of our display, we encourage others to see the beautiful potential in collective interaction with note-taking practices. In doing so, our work continues ‘to live, and act, and serve the future hour’.

Megan Beech, MPhil Modern and Contemporary Literature

Megan Beech, MPhil Modern and Contemporary Literature

Megan is a performance poet and created these two short poetry films in response to her experiences at the Wordsworth Trust and studying notebooks on Dr Ruth Abbott’s course:

Trust Wordsworth: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2BAv_9Mg5s

‘O! This is Our Tale Too!’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3UP_obyUTI

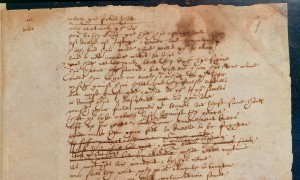

n image from the manuscript of Christina Rossetti’s ‘Sing Song’, the subject of Mina Gorji’s paper at the History of Material Texts seminar on Thursday. It’s an anthology of nursery rhymes, charming and faintly macabre in equal measure, as in this ceremonious poem for a dead thrush, and illustrated in faint pencil-sketches by the author. You can view the whole book

n image from the manuscript of Christina Rossetti’s ‘Sing Song’, the subject of Mina Gorji’s paper at the History of Material Texts seminar on Thursday. It’s an anthology of nursery rhymes, charming and faintly macabre in equal measure, as in this ceremonious poem for a dead thrush, and illustrated in faint pencil-sketches by the author. You can view the whole book  A backwater lay-by off the M5, Junction 24, three days before Christmas. A covert exchange of an unknown document, protected only by an iPad case, occurs between man, whippet and young woman. Shady as it may seem, this is not the stuff of reconnaissance but curation. This nineteenth-century commonplace book replete with beautiful illustrations, kindly donated by John and Caroline Robinson, now lies in situ on the first floor of the English Faculty, at the heart of the inaugural exhibition of the Centre for Material Texts. The exhibition, curated by myself and my MPhil colleagues on Dr Ruth Abbott’s Writers’ Notebooks course, focuses on commonplace books and the ways in which they acted as repositories for the recording of daily life in the nineteenth century. From passages of the Bible to Byron, musings on God to sketches of the family dogs, the commonplace book offered a powerful collective storehouse for the miscellanies and medleys of material that amassed at the center of communal family life.

A backwater lay-by off the M5, Junction 24, three days before Christmas. A covert exchange of an unknown document, protected only by an iPad case, occurs between man, whippet and young woman. Shady as it may seem, this is not the stuff of reconnaissance but curation. This nineteenth-century commonplace book replete with beautiful illustrations, kindly donated by John and Caroline Robinson, now lies in situ on the first floor of the English Faculty, at the heart of the inaugural exhibition of the Centre for Material Texts. The exhibition, curated by myself and my MPhil colleagues on Dr Ruth Abbott’s Writers’ Notebooks course, focuses on commonplace books and the ways in which they acted as repositories for the recording of daily life in the nineteenth century. From passages of the Bible to Byron, musings on God to sketches of the family dogs, the commonplace book offered a powerful collective storehouse for the miscellanies and medleys of material that amassed at the center of communal family life. The unconventional method through which our exhibition materials were acquired proves apropos, given the unusual conditions under which the birth of our interest in commonplace books occurred. In another intrepid motorway adventure: a six hour, 250-mile minibus journey (nobly helmed by Ruth Abbott) with eight complete strangers, our group’s first weekend in Cambridge, was in fact spent in Grasmere, Cumbria working at the Wordsworth Trust. Guided by Ruth and curator Jeff Cowton we spent a full two days nestled in the archive, immersed in manuscripts and the materials which made them. It was a weekend stuffed with stuff. We created Thomas Bewick prints on a nineteenth-century printing press. We learned how to bind books on a sewing frame. Quills were carved and inks were made. Paste was pressed from pulp into paper (with the aid of a craftsman’s deckle and an improvised flattening dance on top of it). In a flurry of high spirits, fumbling with spirit-levels, our exhibition on the Wordsworth family commonplace books was installed.

The unconventional method through which our exhibition materials were acquired proves apropos, given the unusual conditions under which the birth of our interest in commonplace books occurred. In another intrepid motorway adventure: a six hour, 250-mile minibus journey (nobly helmed by Ruth Abbott) with eight complete strangers, our group’s first weekend in Cambridge, was in fact spent in Grasmere, Cumbria working at the Wordsworth Trust. Guided by Ruth and curator Jeff Cowton we spent a full two days nestled in the archive, immersed in manuscripts and the materials which made them. It was a weekend stuffed with stuff. We created Thomas Bewick prints on a nineteenth-century printing press. We learned how to bind books on a sewing frame. Quills were carved and inks were made. Paste was pressed from pulp into paper (with the aid of a craftsman’s deckle and an improvised flattening dance on top of it). In a flurry of high spirits, fumbling with spirit-levels, our exhibition on the Wordsworth family commonplace books was installed. Like the chain lines and watermarks we spent the days studying in manuscripts, through curatorial collaboration we had impressed a profound mark on each other. The silence, sky and space of the Lakes and our collective academic endeavour had bound us together as tightly as the spines of the nineteenth-century treasures that lay on the archive’s shelves. What was particularly pertinent in creating this exhibition, born into being from deeply felt fellow-feeling from all parties, was that it chronicles and encourages the communal sharing of thought. The addition of our modern commonplace book to the display invites exhibition-goers to participate in shared forms of notetaking, to add their scraps and fragments of experience, their inmost thoughts, their favourite quotations and aid the creation of a beautiful, diverse collective text.

Like the chain lines and watermarks we spent the days studying in manuscripts, through curatorial collaboration we had impressed a profound mark on each other. The silence, sky and space of the Lakes and our collective academic endeavour had bound us together as tightly as the spines of the nineteenth-century treasures that lay on the archive’s shelves. What was particularly pertinent in creating this exhibition, born into being from deeply felt fellow-feeling from all parties, was that it chronicles and encourages the communal sharing of thought. The addition of our modern commonplace book to the display invites exhibition-goers to participate in shared forms of notetaking, to add their scraps and fragments of experience, their inmost thoughts, their favourite quotations and aid the creation of a beautiful, diverse collective text. Speaking to other students who have visited Grasmere, at a recent meeting with the Wordsworth Trust at London’s Brigham Young Institute, I further realised the true powerful potential of the material. Through awe-filled eyes, each sentence suffused with a quasi-religious fervour, they recounted the moment they were allowed to see a first edition of Lyrical Ballads and handle Dorothy Wordsworth’s real notebooks. In fact, the Wordsworth Trust’s website proudly proclaims ‘Visit the Wordsworth Museum to see Dorothy’s actual notebooks’. This is something our group reflected upon as we sat around Wordsworth’s ‘actual’ fire in Dove Cottage, reading his poems, souls stirred by the transcendent beauty of breathing life back into words where they were first brought into being. In curating this exhibition, in Grasmere and in Cambridge, and through Ruth Abbott’s phenomenal notebooks course we have relearnt the overwhelming magic of the material, the ability to encounter and interact with the ‘actual’. It is in this kind of engagement with ‘actual’ manuscripts, notebooks and papers that ‘with an eye made quiet by the power/Of harmony, and the deep power of joy, / We see into the life of things’.

Speaking to other students who have visited Grasmere, at a recent meeting with the Wordsworth Trust at London’s Brigham Young Institute, I further realised the true powerful potential of the material. Through awe-filled eyes, each sentence suffused with a quasi-religious fervour, they recounted the moment they were allowed to see a first edition of Lyrical Ballads and handle Dorothy Wordsworth’s real notebooks. In fact, the Wordsworth Trust’s website proudly proclaims ‘Visit the Wordsworth Museum to see Dorothy’s actual notebooks’. This is something our group reflected upon as we sat around Wordsworth’s ‘actual’ fire in Dove Cottage, reading his poems, souls stirred by the transcendent beauty of breathing life back into words where they were first brought into being. In curating this exhibition, in Grasmere and in Cambridge, and through Ruth Abbott’s phenomenal notebooks course we have relearnt the overwhelming magic of the material, the ability to encounter and interact with the ‘actual’. It is in this kind of engagement with ‘actual’ manuscripts, notebooks and papers that ‘with an eye made quiet by the power/Of harmony, and the deep power of joy, / We see into the life of things’. Through our immersion in the material practices from which texts develop, we learnt to cultivate a fresh appreciation for the ways in which literature is embodied and presented. The afterlives of the work we have done with these exhibitions, and the study of notebooks and manuscripts in general, like Wordsworth’s River Duddon, flow on endlessly. From future PhD projects to the reinstallation of the commonplace book exhibition in Cambridge ‘Still glides the Stream, and shall for ever glide;/The Form remains, the Function never dies’. We hope that in this latest reimagining of our display, we encourage others to see the beautiful potential in collective interaction with note-taking practices. In doing so, our work continues ‘to live, and act, and serve the future hour’.

Through our immersion in the material practices from which texts develop, we learnt to cultivate a fresh appreciation for the ways in which literature is embodied and presented. The afterlives of the work we have done with these exhibitions, and the study of notebooks and manuscripts in general, like Wordsworth’s River Duddon, flow on endlessly. From future PhD projects to the reinstallation of the commonplace book exhibition in Cambridge ‘Still glides the Stream, and shall for ever glide;/The Form remains, the Function never dies’. We hope that in this latest reimagining of our display, we encourage others to see the beautiful potential in collective interaction with note-taking practices. In doing so, our work continues ‘to live, and act, and serve the future hour’. Megan Beech, MPhil Modern and Contemporary Literature

Megan Beech, MPhil Modern and Contemporary Literature