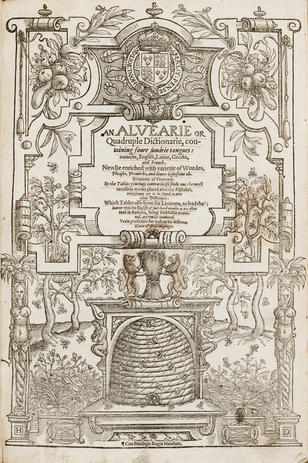

There’s much online buzzing this evening about the purported discovery (on eBay!) of Shakespeare’s dictionary–a copy of Baret’s An Alvearie, or Quadruple Dictionarie, first published in 1580, supposedly annotated by the playwright. I haven’t had time to read the lavish publication in which two intrepid antiquarian booksellers, George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler, justify their claim. So I don’t know quite what has led them to the extraordinary conclusion that they have uncovered a literary goldmine. But I have spent an hour ogling the high-quality digital images that they have generously supplied on the project’s beautifully-produced website. On the basis of a brief look, I’m happy to report that we can all go to bed at the usual time. There is absolutely no reason to believe that Shakespeare was the annotator of the volume.

There’s much online buzzing this evening about the purported discovery (on eBay!) of Shakespeare’s dictionary–a copy of Baret’s An Alvearie, or Quadruple Dictionarie, first published in 1580, supposedly annotated by the playwright. I haven’t had time to read the lavish publication in which two intrepid antiquarian booksellers, George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler, justify their claim. So I don’t know quite what has led them to the extraordinary conclusion that they have uncovered a literary goldmine. But I have spent an hour ogling the high-quality digital images that they have generously supplied on the project’s beautifully-produced website. On the basis of a brief look, I’m happy to report that we can all go to bed at the usual time. There is absolutely no reason to believe that Shakespeare was the annotator of the volume.

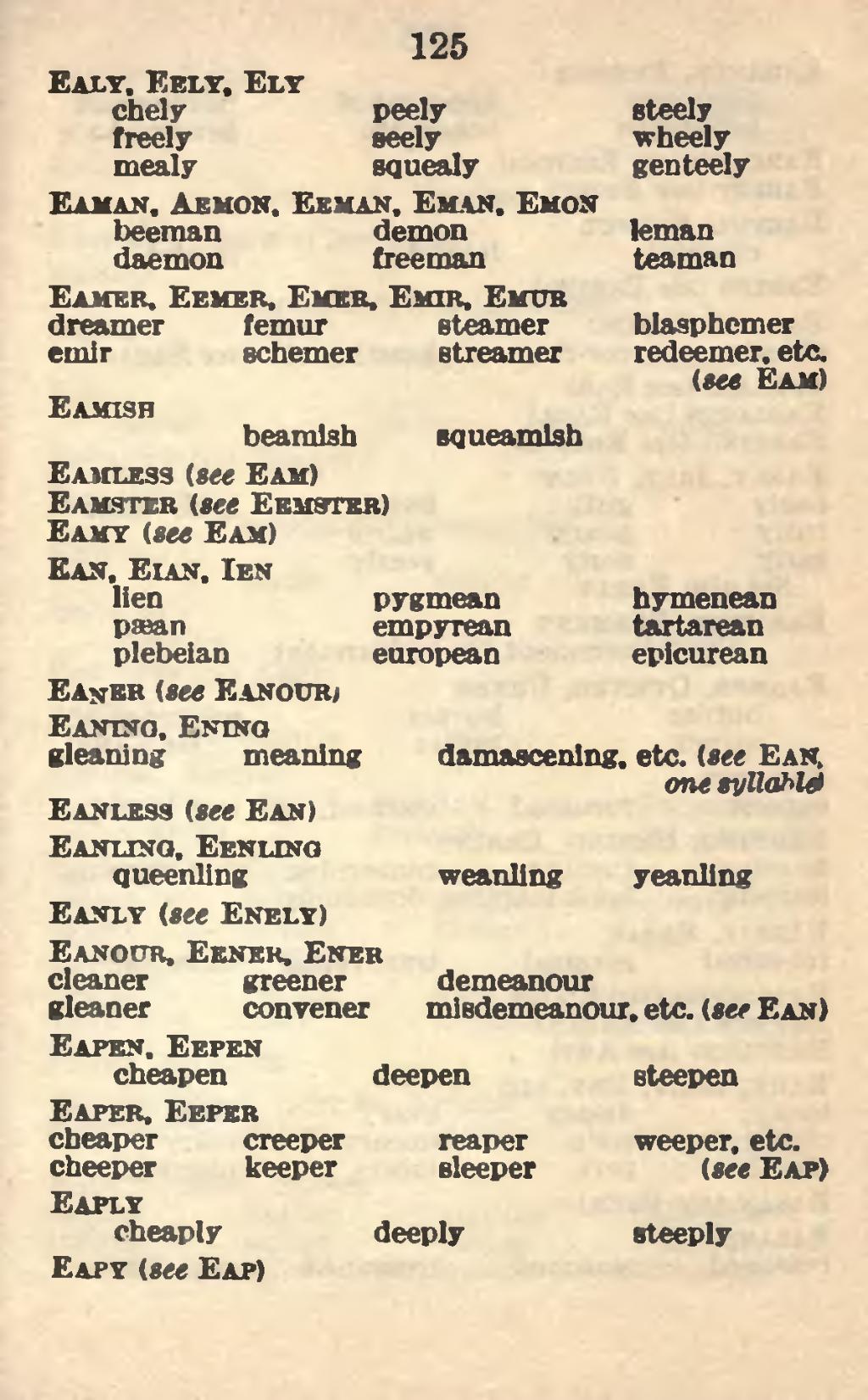

The dictionary is certainly thickly annotated–as are many dictionaries of the period. One of the main jobs that the annotations do is to make up for missing entries in the text, supplying English headings or lemmas where they are lacking, and sometimes offering translations, particularly into French. This reader wants to improve their book–as many early modern readers did. And this reader wants to be able to speak French, copying down sometimes quite obscure idioms and phrases in order to get the trick of the language. So the book will be useful for those who want to study the process of language-acquisition in the sixteenth century. And it will delight those, like me, who love to work with annotated books. Beyond that, it may prove to be something of a damp squib.

I recently caught up with my colleague Simon Jarvis’s essay ‘

I recently caught up with my colleague Simon Jarvis’s essay ‘