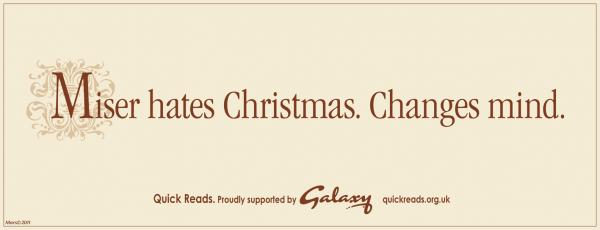

Galaxy – as in the chocolate bars – are currently running a promotion offering a free Kindle e-book with every bar bought. The campaign tells us some interesting things about how people are using e-books and what this means for the future. It shows that a sort of leisure reading that’s been associated with women for at least two hundred years hasn’t been changed by the coming of the Kindle and that – paradoxically – people still want physical books.

The first thing to note is that this is a reworking of a campaign first run in 2009. That promotion involved Galaxy giving away 1 million physical books. Obviously the decision to move to e-books is a sign that marketers reckon e-books are now popular enough to count as mainstream – at least for Galaxy buyers.

What’s more significant is the fact that Galaxy are using e-books to target exactly the same set of associations that they used physical books to reach. Describing the first campaign, Galaxy’s Senior Brand Manager Sally Mellor said that ‘Women love reading, and women love chocolate.’ The campaign worked ‘by inviting them to “melt into a good book”’. Mediacom, the agency behind the campaign, said that they were able to ‘build an association between Galaxy and this moment of female indulgence’.

Affordable indulgence is at the heart of the Galaxy brand – hence their long-running slogan ‘why have cotton when you could have silk?’. That’s what the poster campaign for the new promotion tries to evoke. Those behind it reckon that the women who own Kindles use them in search of the same kind of convenient, cheap, but self-consciously indulgent experience they’re meant to associate with Galaxy.

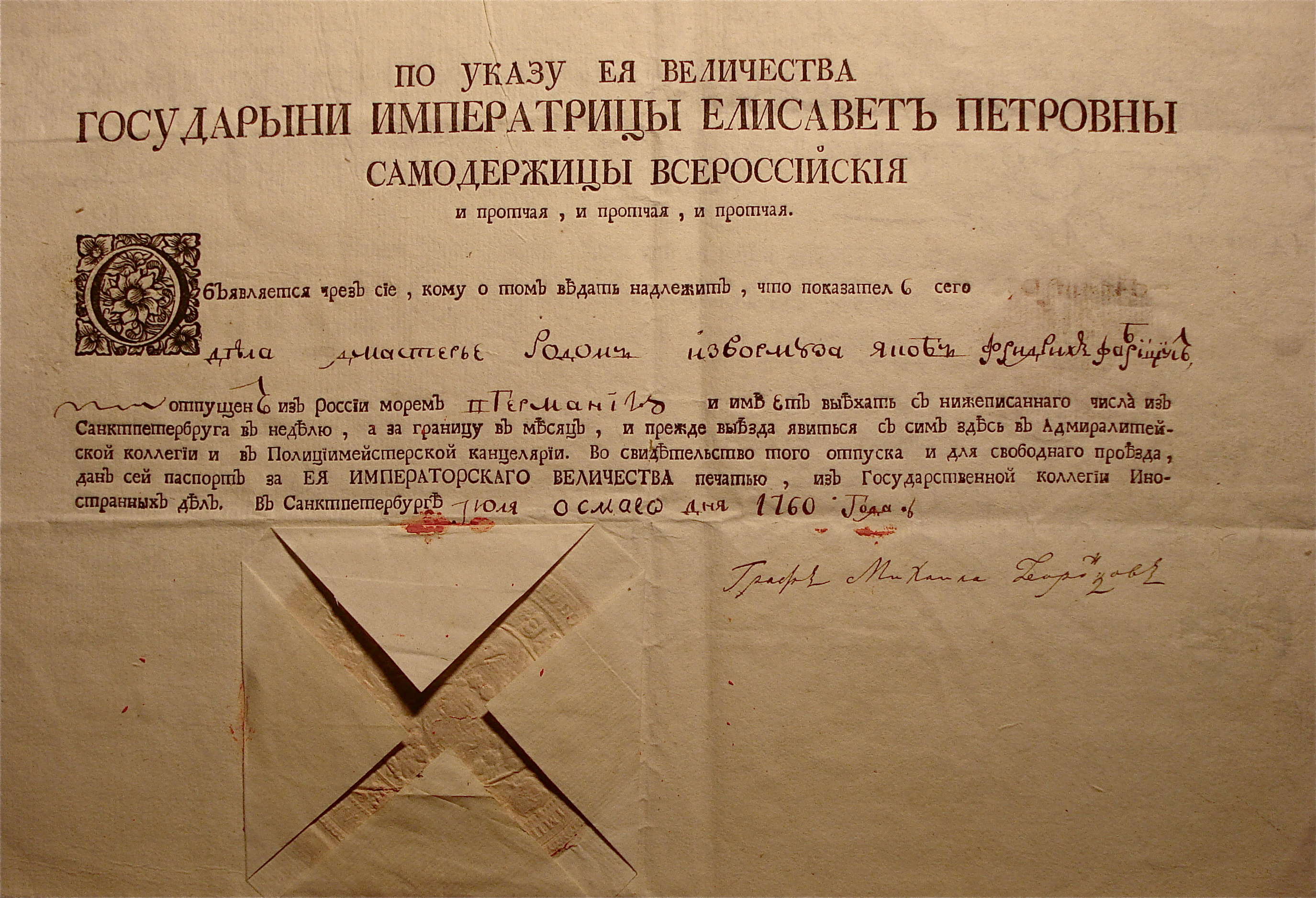

So what does this tell us? The most important lesson is that, when it comes to e-books, many women see them as a way of accessing a traditional sort of reading. Galaxy’s posters don’t include pictures of Kindles but, instead, have images of physical books with a distinctly nineteenth-century appearance. People want to imagine that reading an e-book is just like reading a nice old copy they can feel in their hands. As with luxury brands, heritage is part of the package.

What’s more, props such as bookmarks appear on some posters to make it even easier to imagine the physical work of reading a paper book. There’s an interesting link here to the branded bookmarks which were made for the old campaign. The physical thing is an important part of the sense of indulgence.

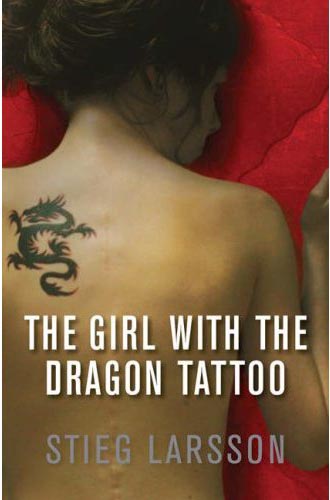

This taps into readers’ aspirations. Despite the fact that the titles you can download are all contemporary novels (mostly chick-lit), the posters parody Victorian classics. One starts ‘It was the best of times, it was the best of times…’. So whatever it is they’re actually getting, people at least want to entertain the possibility that they might read a classic on their Kindle.

These lessons fit with what we’ve already seen with successful e-book readers. In short, the more it acts like a traditional paper book, the more people like it. To these readers, the e-book is a transformative but not a revolutionary technology. What does that mean? Well, it’s transforming the ease with which books can be bought or given away, how much they cost, and where and when they can be used. But it’s not revolutionising the way readers think of books. In a broad sense, Galaxy thinks that lots of women want the same experience of indulgent me-time that a novel buyer of the 1870s – or a library subscriber of the 1790s – would understand.

What does this mean for the future? Happily for book-shops, it shows us that lots of readers don’t think e-books are an upgrade for obsolete paper books. Instead, they’re substitutes for the ‘real’ thing. Until this changes, they’ll always be a market for physical books. Of course, shops might sell less cheap paperbacks. But just as Hotel Chocolat can survive in a world where you can get a galaxy bar for 70p out of a vending machine, there’s a chance for bookshops to thrive by offering readers genuine indulgence. And those publishers who’ve started issuing deluxe editions of classics are on the right track.

I recently caught up with my colleague Simon Jarvis’s essay ‘

I recently caught up with my colleague Simon Jarvis’s essay ‘