It’s over a week now since our CMT/Southampton conference ‘Newes from No Place’, on the life and works of John Taylor, the Water-Poet (1578-1653). Held at Gonville and Caius College on 14-15 September, it featured thirteen speakers who offered many different perspectives on Taylor’s gargantuan oeuvre. We came together in the belief that Taylor, a self-professed amphibian who was at once a boatman on the river Thames (the equivalent of the London cab driver of today) and a hugely prolific writer, was an extraordinary figure in extraordinary times. Our aim was to set this incessant traveller in motion again, to see what he had to say to literary critics and cultural historians in the twenty-first century.

It’s over a week now since our CMT/Southampton conference ‘Newes from No Place’, on the life and works of John Taylor, the Water-Poet (1578-1653). Held at Gonville and Caius College on 14-15 September, it featured thirteen speakers who offered many different perspectives on Taylor’s gargantuan oeuvre. We came together in the belief that Taylor, a self-professed amphibian who was at once a boatman on the river Thames (the equivalent of the London cab driver of today) and a hugely prolific writer, was an extraordinary figure in extraordinary times. Our aim was to set this incessant traveller in motion again, to see what he had to say to literary critics and cultural historians in the twenty-first century.

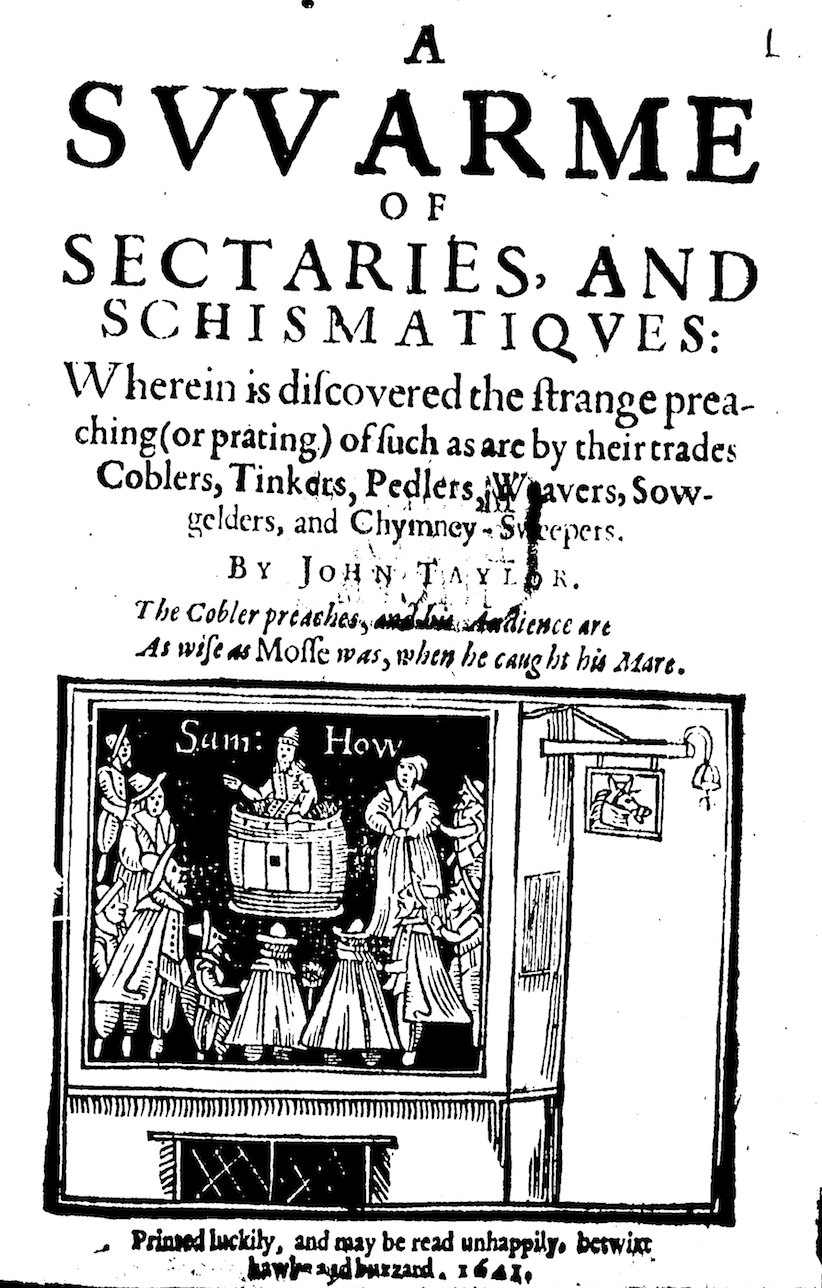

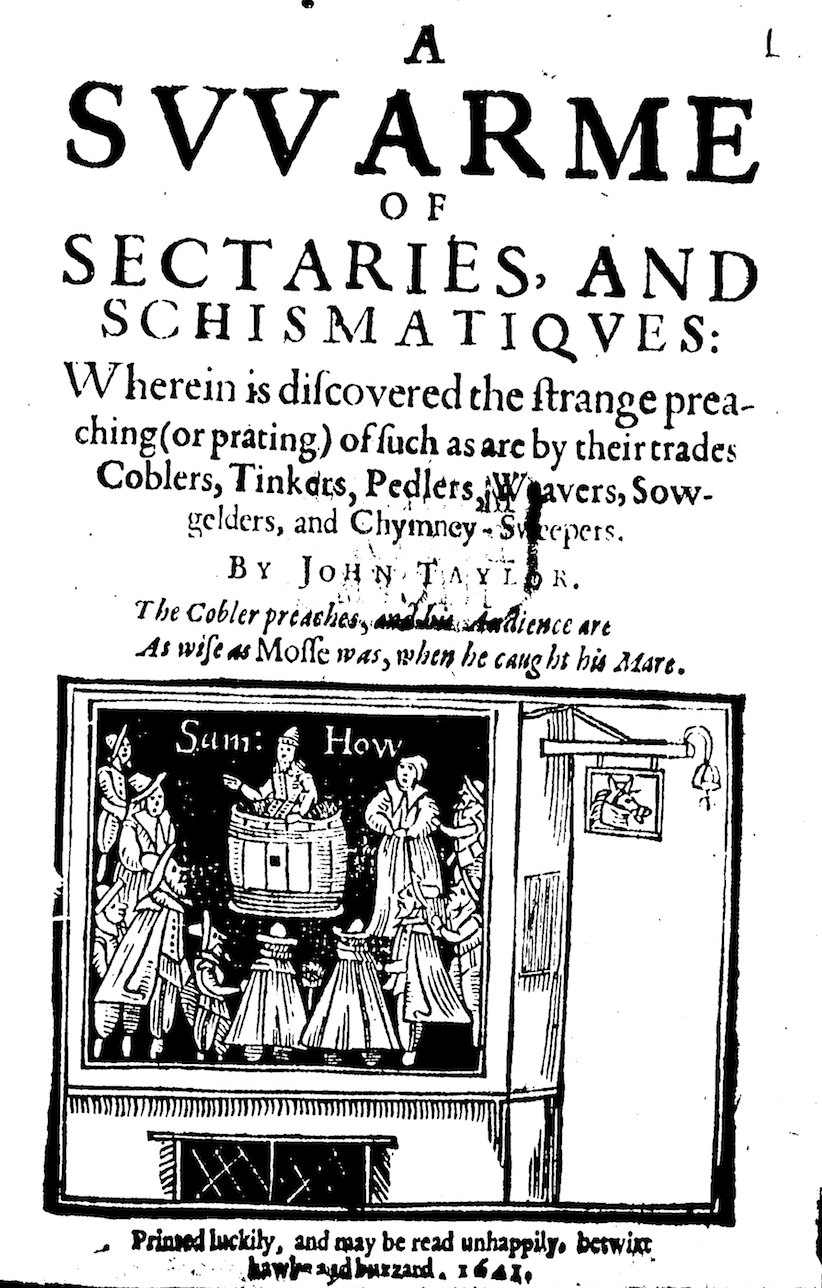

Proceedings were initiated by Bernard Capp, author of a magisterial survey of Taylor’s career, who reconsidered Taylor’s output during the Civil War years of the 1640s. Driven out of London for his Royalist sympathies, by 1643 Taylor found himself in Oxford, defending the King’s cause in pamphlets so numerous that the printing presses were unable to keep up with them. Analysing those pamphlets afresh, Capp concluded that they were not the kind of thing that might convince an adversary, but were intended to boost Royalist morale, at the same time as they settled scores with individual adversaries. One particularly resonant concern of Taylor’s was ‘fake news’; some of his pamphlets peddled their own spoof stories, while others attempted to set the record straight through first-hand reportage. After Capp had offered this wide-angle view, Abigail Shinn homed in on one pamphlet, The Conversion, Confession, Contrition, Coming to Himselfe, & Advice, of a Mis-led, Ill-bred, Rebellious Roundhead (1643). Drawing on Andrew McRae’s argument about the financial productivity of Taylor’s journeying, Shinn read this satire on a convert to puritanism as an attack on unproductive travel—spinning in circles around a ‘round head’. Parodying the puritan practice of ‘sermon-gadding’ to hear particular preachers, a staple element in spiritual life-writing of the period, Taylor’s Roundhead displays an inordinate movement linked with madness and vagrancy. Shinn showed us how that movement registers in Taylor’s style, which starts gadding wildly in imitation of its subject.

Ros King’s paper celebrated Taylor’s mobility, as a counterweight to any received picture of the early modern period as a time of stasis and social conservatism. In travelling, Taylor was finding out what it meant to be English (or British) in his day, but at the same time he was remaking social relations and experimenting with the more horizontal ties that could be created by urban life and the marketplace of print. His ability to celebrate the everyday and to overturn hierarchies (as when he got a pair of schoolboys, rather than aristocrats or men of letters, to supply the commendation for a book) points to a new vision of the social order. Challenging us to think counterfactually, King asked whether a more Taylorian Britain might not have had to endure the revolution of the 1640s.  She was followed by Ariel Hessayon, who began by announcing that he was not going to give the paper he had intended to give, because he no longer believed that the work he had planned to discuss was written by Taylor. He went on to demonstrate that numerous works of the 1640s and 1650s have been ascribed to Taylor on the flimsiest foundations (by whom is not yet clear). Taylor’s authorship has been inferred from the most tenuous evidence: a reused woodblock, some promising-looking initials (‘J.T.’ or ‘T.J.’) on the title-page, or the presence of Taylorian tricks of style that could have been borrowed by any able satirist. Invoking the spectre of the Ranter debates of the 1980s, in which historians speculated that a well-known Civil War splinter group was no more than the ‘fake news’ whipped up by the conservatives of the day, Hessayon asked whether we would prefer a maximal Taylor, who encompasses everything that has been pinned on him, however dubiously, or a minimal Taylor, who might have written none of ‘his’ works? Finding the golden mean between these extremes is going to take some time.

She was followed by Ariel Hessayon, who began by announcing that he was not going to give the paper he had intended to give, because he no longer believed that the work he had planned to discuss was written by Taylor. He went on to demonstrate that numerous works of the 1640s and 1650s have been ascribed to Taylor on the flimsiest foundations (by whom is not yet clear). Taylor’s authorship has been inferred from the most tenuous evidence: a reused woodblock, some promising-looking initials (‘J.T.’ or ‘T.J.’) on the title-page, or the presence of Taylorian tricks of style that could have been borrowed by any able satirist. Invoking the spectre of the Ranter debates of the 1980s, in which historians speculated that a well-known Civil War splinter group was no more than the ‘fake news’ whipped up by the conservatives of the day, Hessayon asked whether we would prefer a maximal Taylor, who encompasses everything that has been pinned on him, however dubiously, or a minimal Taylor, who might have written none of ‘his’ works? Finding the golden mean between these extremes is going to take some time.

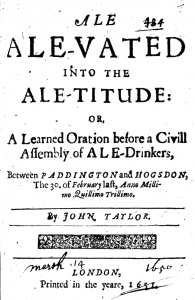

The first day was rounded off by three papers, the first by Anthony Ossa-Richardson on Taylor’s learning. Drawing on Taylor’s early poetic credo in The Nipping and Snipping of Abuses (1614), Ossa-Richardson noted his opposition to mimicry; Taylor thought that the poet should be a creator-figure who produces something from nothing, and not a mere copyist or translator. He went on to analyse Taylor’s nonsense, showing how one batch of nonsense (in the 1651 Nonsence Upon Sence) creates its nonsensicality by cutting and pasting lines from an earlier, less nonsensical collection (the Mad verse, sad verse, glad verse and bad verse cut out, and slenderly sticht together of 1644). Taylor’s habits of plagiarism and self-plagiarism thus raise important questions about his aesthetic. Adam Smyth took up the baton with a consideration of Taylor and error, noting his playful way with errata lists and linking it with his wider ‘print-shop presence’, his determination to be there (‘an unsilenceable voice’) in every aspect of his books. The idea of error is also linked with wandering, and with Taylor’s identity as a traveller whose whole oeuvre is constitutively erroneous; Smyth drew attention to the strange miscellaneity of the 1630 folio All the Workes, its resistance to order or organization, and the sense that its binding together of so many miscellaneous pamphlets is also a form of scattering and dispersal. Finally in this session, Jason Scott-Warren proposed an ‘Exuvial Taylor’, drawing on the works of the anthropologist Alfred Gell to consider the writer in terms of the metaphorical ‘skins’ that he shed or re-inhabited during his lifetime. This led to a view of Taylor as a writer devoted to blazing or blazoning—the trumpeting of his own reputation and that of a range of bizarre things (geese, clean linen, twelve-pence, hemp-seed). But, Scott-Warren suggested, Taylor’s blazings are always ironic, and are thus symptomatic of a print marketplace that can put a celebrity author’s name into everyone’s mouth, but cannot ensure that they pay for his wares.

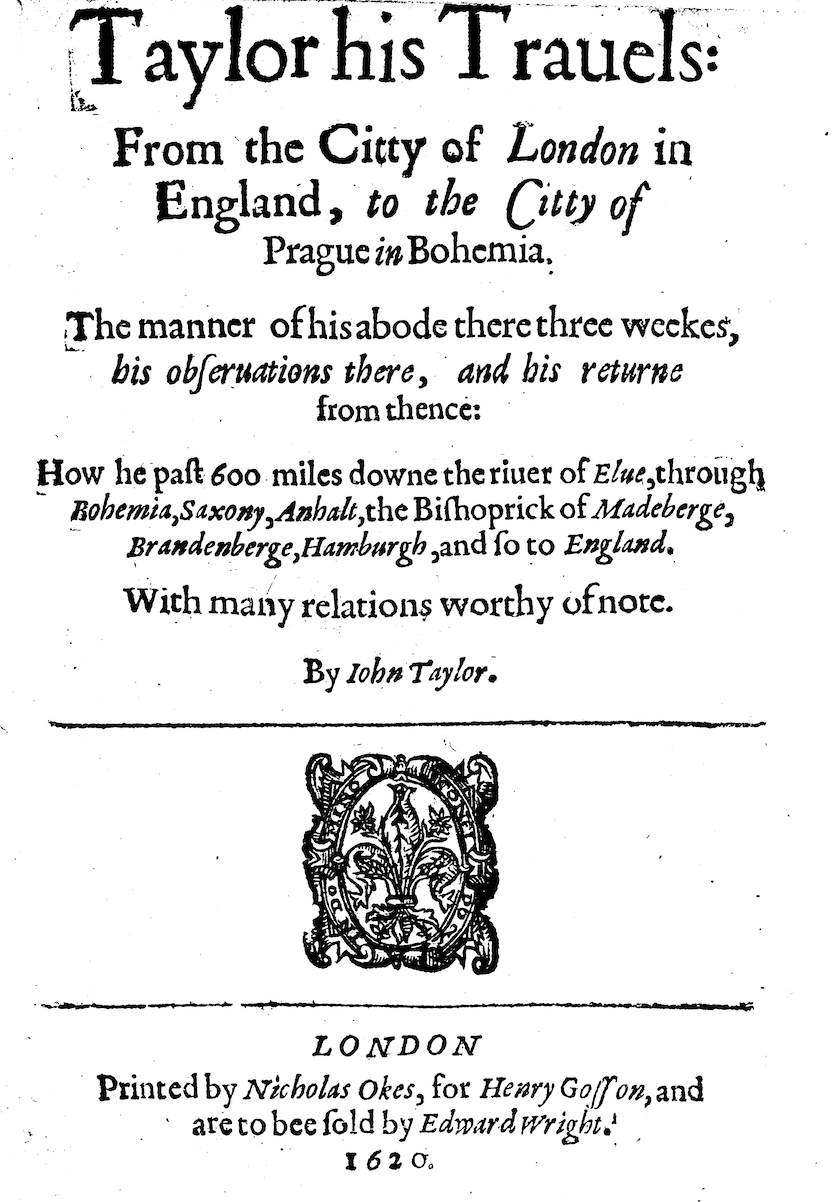

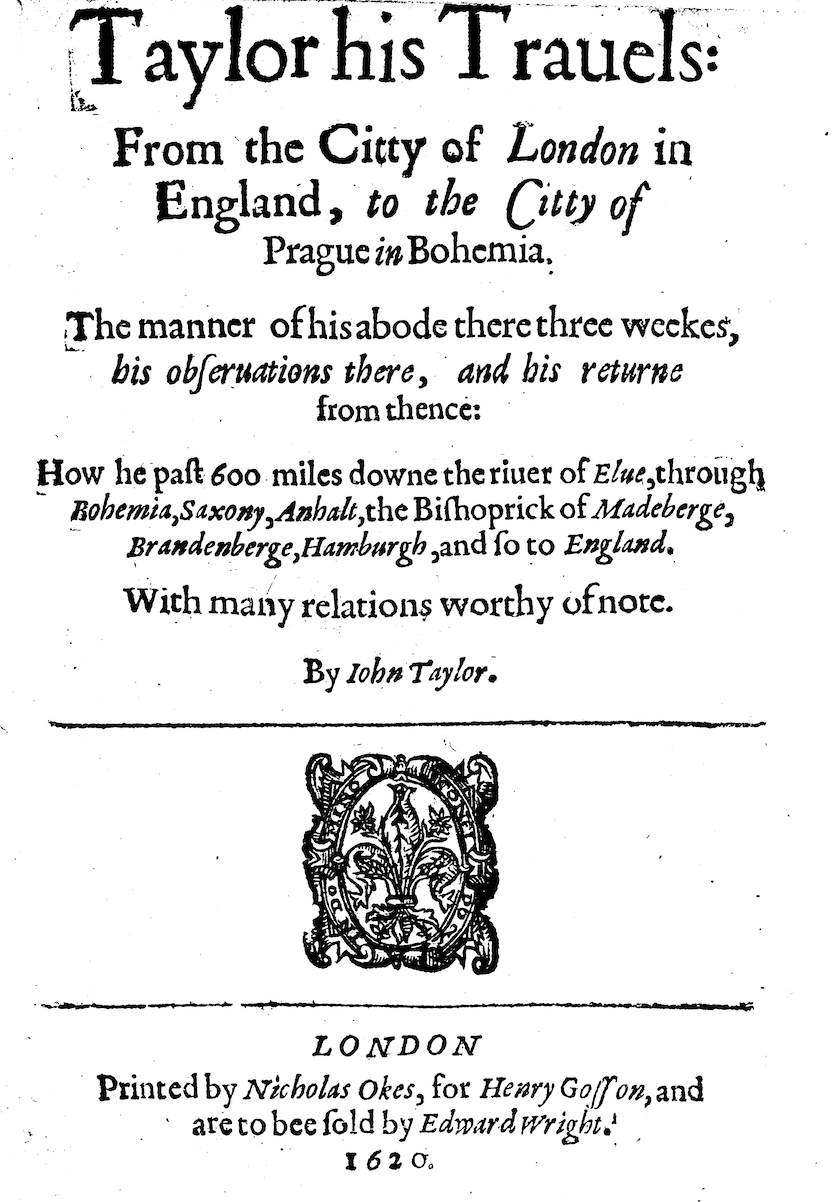

Day 2 struck out across Europe with Kirsty Rolfe’s paper on Taylor’s imagined geographies, setting his 1620 journey to Prague in the context of the news culture of the Thirty Years’ War. At this sticky political moment, when the appetite for news was at its height, James I issued a proclamation against the excess of licentious speech in matters of state—a classic case of an act of censorship that could not bring itself to say exactly what it wanted to censor. Unpicking Taylor’s satire on 1620s news culture, Rolfe suggested his sharp awareness of the intricacies of the circulation of information, and his disingenousness in claiming to stand outside it. Jemima Matthews brought us back to London and to Taylor’s Thames, including his involvement in the production of mayoral pageants, in which the river was converted into a fantastical space of performance. Such entertainments had a long tradition of broaching serious matters in the guise of theatre, and Taylor’s contribution to the genre, the 1634 Triumphs of Fame and Honour, was no exception, reminding the Mayor of his responsibilities to the river. Matthews set the pageant in relation to a variety of monopolistic schemes to exploit the river, showing how Taylor’s pamphlet contributed to the representation of the Thames as a space of financial opportunity.

Day 2 struck out across Europe with Kirsty Rolfe’s paper on Taylor’s imagined geographies, setting his 1620 journey to Prague in the context of the news culture of the Thirty Years’ War. At this sticky political moment, when the appetite for news was at its height, James I issued a proclamation against the excess of licentious speech in matters of state—a classic case of an act of censorship that could not bring itself to say exactly what it wanted to censor. Unpicking Taylor’s satire on 1620s news culture, Rolfe suggested his sharp awareness of the intricacies of the circulation of information, and his disingenousness in claiming to stand outside it. Jemima Matthews brought us back to London and to Taylor’s Thames, including his involvement in the production of mayoral pageants, in which the river was converted into a fantastical space of performance. Such entertainments had a long tradition of broaching serious matters in the guise of theatre, and Taylor’s contribution to the genre, the 1634 Triumphs of Fame and Honour, was no exception, reminding the Mayor of his responsibilities to the river. Matthews set the pageant in relation to a variety of monopolistic schemes to exploit the river, showing how Taylor’s pamphlet contributed to the representation of the Thames as a space of financial opportunity.

Andrew McRae and Alice Hunt presented papers that took us to opposite ends of Taylor’s career. McRae took on the early works (meaning the 30-odd pamphlets that he published between 1612 and 1621), showing us how Taylor became the Water-Poet, a writer who rather than effacing his origins and his occupation chose to flaunt them. Taylor began as a surprisingly well-connected writer, but in his print wars with Fenner and Coryate came increasingly to define himself by his exclusion from elite literary circles. He was also relentlessly experimental, trying out numerous genres until he began to find his metier around 1620—at which time he also learnt to equate poetry with labour, in verse that represented a reinvention of georgic. Alice Hunt explored the Taylor of the 1650s, who was (after his ejection from London) no longer a Water-Poet, but a land-traveller undertaking a kind of existential journeying in search of the identity of the new, kingless Britain. Hunt noted the weariness of the late pamphlets, Taylor ‘limping through the English countryside on a knackered nag’. But he had not lost his eye for the evocative detail, and his writing was subtle in its probing of political allegiances. Exploring Taylor’s evocation of the headless kingdom allows us to see that his royalism was not, and perhaps never had been, particularly reverend.

Will May’s paper addressed itself to Taylor’s place in the history of whimsy, via a long-term history of nonsense. Drawing on Michael Dobson’s suggestion that the history of English nonsense might be the history of works that use the word ‘Basingstoke’ for comic effect, May led us into a history of whimsy as a kind of fever of the brain—a fever that might be brought on by trying to trace the origins of the word ‘whimsy’ itself. Finally May set Taylor in a tradition of  performative, public writer-eccentrics, including Thomas Hood and Marianne Moore. Altogether less whimsical was Johann Gregory’s paper, reporting back on his recent project to live-tweet John Taylor’s travels around Wales in 1652 (#WaterPoet2017). This digital journeying was an innovative form of research that allowed Gregory to see where Taylor had elided aspects of his travels, raising questions about the faithfulness of seemingly spontaneous eyewitness accounts. But it was principally a form of public engagement that echoed Taylor’s own projects, and suggested their ongoing vibrancy in the present day. Taylor has, we suspect, many travels left in him.

performative, public writer-eccentrics, including Thomas Hood and Marianne Moore. Altogether less whimsical was Johann Gregory’s paper, reporting back on his recent project to live-tweet John Taylor’s travels around Wales in 1652 (#WaterPoet2017). This digital journeying was an innovative form of research that allowed Gregory to see where Taylor had elided aspects of his travels, raising questions about the faithfulness of seemingly spontaneous eyewitness accounts. But it was principally a form of public engagement that echoed Taylor’s own projects, and suggested their ongoing vibrancy in the present day. Taylor has, we suspect, many travels left in him.