Yesterday the CMT convened a one-day colloquium entitled ‘The Academic Book of the Future: Evolution or Revolution?’ This was part of Cambridge’s contribution to a host of events being held across the UK in celebration of the first ever Academic Book Week, which is itself an offshoot of the AHRC-funded ‘Academic Book of the Future’ project. The aim of that project is both to raise awareness of academic publishing and to explore how it might change in response to new digital technologies and changing academic cultures. We were delighted to have Samantha Rayner, the PI on the project, to introduce the event.

Yesterday the CMT convened a one-day colloquium entitled ‘The Academic Book of the Future: Evolution or Revolution?’ This was part of Cambridge’s contribution to a host of events being held across the UK in celebration of the first ever Academic Book Week, which is itself an offshoot of the AHRC-funded ‘Academic Book of the Future’ project. The aim of that project is both to raise awareness of academic publishing and to explore how it might change in response to new digital technologies and changing academic cultures. We were delighted to have Samantha Rayner, the PI on the project, to introduce the event.

The first session kicked off with a talk from Rupert Gatti, Fellow in Economics at Trinity and one of the founders of Open Book Publishers (www.openbookpublishers.com), explaining ‘Why the Future is Open Access’. Gatti contrasted OA publishing with ‘legacy’ publishing and emphasized the different orders of magnitude of the audience for these models. Academic books published through the usual channels were, he contended, failing to reach 99% of their potential audience. They were also failing to take account of the possibilities opened up by digital media for embedding research materials and for turning the book an ongoing project rather than a finished article. The second speaker in this session, Alison Wood, a Mellon/Newton postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities in Cambridge, reflected on the relationship between academic publishing and the changing institutional structures of the university. She urged us to look for historical precedents to help us cope with current upheavals, and called in the historian Anthony Grafton to testify to the importance of intellectual communities and institutions to the seemingly solitary labour of the academic monograph. In Wood’s analysis, we need to draw upon our knowledge of the changing shape of the university as a collective (far more postdocs, far more adjunct teachers, far more globalization) when thinking about how academic publishing might develop. We can expect scholarly books of the future to take some unusual forms in response to shifting material circumstances.

The day was punctuated by a series of ‘views’ from different Cambridge institutions. The first was offered by David Robinson, the Managing Director of Heffers, which has been selling books in Cambridge since 1876. Robinson focused on the extraordinary difference between his earlier job, in a university campus bookshop, and his current role. In the former post, in the heyday of the course textbook, before the demise of the net book agreement and the rise of the internet, selling books had felt a little like ‘playing shops’. Now that the textbook era is over, bookshops are less tightly bound into the warp and weft of universities, and academic books are becoming less and less visible on the shelves even of a bookshop like Heffers. Robinson pointed to the ‘crossover’ book, the academic book that achieves a large readership, as a crucial category in the current bookselling landscape. He cited Thomas Piketty’s Capital as a recent example of the genre.

The day was punctuated by a series of ‘views’ from different Cambridge institutions. The first was offered by David Robinson, the Managing Director of Heffers, which has been selling books in Cambridge since 1876. Robinson focused on the extraordinary difference between his earlier job, in a university campus bookshop, and his current role. In the former post, in the heyday of the course textbook, before the demise of the net book agreement and the rise of the internet, selling books had felt a little like ‘playing shops’. Now that the textbook era is over, bookshops are less tightly bound into the warp and weft of universities, and academic books are becoming less and less visible on the shelves even of a bookshop like Heffers. Robinson pointed to the ‘crossover’ book, the academic book that achieves a large readership, as a crucial category in the current bookselling landscape. He cited Thomas Piketty’s Capital as a recent example of the genre.

Our second panel was devoted to thinking about the ‘Academic Book of the Near-Future’, and our speakers offered a series of reflections on the current state of play. The first speaker, Samantha Rayner (Senior Lecturer in the Department of Information Studies at UCL and ‘Academic Book of the Future’ PI), described the progress of the project to date. The first phase had involved starting conversations with numerous stakeholders at every point in the production process, to understand the nature of the systems in which the academic book is enmeshed. Rayner called attention to the volatility of the situation in which the project is unfolding—every new development in government higher education policy forces a rethink of possible futures. She also stressed the need for early-career scholars to receive training in the variety of publishing avenues that are open to them. Richard Fisher, former Managing Director of Academic Publishing at CUP, took up the baton with a talk about the ‘invisibles’ of traditional academic publishing—all the work that goes into making the reputation of an academic publisher that never gets seen by authors and readers. Those invisibles had in the past created certain kinds of stability—‘lines’ that libraries would need to subscribe to, periodicals whose names would be a byword for quality, reliable metadata for hard-pressed cataloguers. And the nature of these existing arrangements is having a powerful effect on the ways in which digital technology is (or is not) being adopted by particular publishing sectors.  Peter Mandler, Professor of Modern Cultural History at Cambridge and President of the Royal Historical Society, began by singing the praises of the academic monograph; he saw considerable opportunities for evolutionary rather than revolutionary change in this format thanks to the move to digital. The threat to the monograph came, in his view, mostly from government-induced productivism. The scramble to publish for the REF as it is currently configured leads to a lower-quality product, and threatens to marginalize the book altogether. Danny Kingsley, Head of Scholarly Communication at Cambridge, discussed the failure of the academic community to embrace Open Access, and its unpreparedness for the imposition of OA by governments. She outlined Australian Open Access models that had given academic work a far greater impact, putting an end to the world in which intellectual prestige stood in inverse proportion to numbers of readers.

Peter Mandler, Professor of Modern Cultural History at Cambridge and President of the Royal Historical Society, began by singing the praises of the academic monograph; he saw considerable opportunities for evolutionary rather than revolutionary change in this format thanks to the move to digital. The threat to the monograph came, in his view, mostly from government-induced productivism. The scramble to publish for the REF as it is currently configured leads to a lower-quality product, and threatens to marginalize the book altogether. Danny Kingsley, Head of Scholarly Communication at Cambridge, discussed the failure of the academic community to embrace Open Access, and its unpreparedness for the imposition of OA by governments. She outlined Australian Open Access models that had given academic work a far greater impact, putting an end to the world in which intellectual prestige stood in inverse proportion to numbers of readers.

In the questions following this panel, some anxieties were aired about the extent to which the digital transition might encourage academic publishers to further devolve labour and costs to their authors, and to weaken processes of peer review. How can we ensure that any innovations bring us the best of academic life, rather than taking us on a race to the bottom? There was also discussion about the difficulties of tailoring Open Access to humanities disciplines that relied on images, given the current costs of digital licences; it was suggested that the use of lower-density (72 dpi) images might offer a way round the problem, but there was some vociferous dissent from this view.

After lunch, the University Librarian Anne Jarvis offered us ‘The View from the UL’. The remit of the UL, to safeguard the book’s past for future generations and to make it available to researchers, remains unchanged. But a great deal is changing. Readers no longer perceive the boundaries between different kinds of content (books, articles, websites), and the library is less concerned with drawing in readers and more concerned with pushing out content. The curation and preservation of digital materials, including materials that fall under the rules for legal deposit, has created a set of new challenges. Meanwhile the UL has been increasingly concerned to work with academics in order to understand how they are using old and new technologies in their day-to-day lives, and to ensure that it provides a service tailored to real rather than imagined needs.

After lunch, the University Librarian Anne Jarvis offered us ‘The View from the UL’. The remit of the UL, to safeguard the book’s past for future generations and to make it available to researchers, remains unchanged. But a great deal is changing. Readers no longer perceive the boundaries between different kinds of content (books, articles, websites), and the library is less concerned with drawing in readers and more concerned with pushing out content. The curation and preservation of digital materials, including materials that fall under the rules for legal deposit, has created a set of new challenges. Meanwhile the UL has been increasingly concerned to work with academics in order to understand how they are using old and new technologies in their day-to-day lives, and to ensure that it provides a service tailored to real rather than imagined needs.

The third panel session of the day brought together four academics from different humanities disciplines to discuss the publishing landscape as they perceive it. Abigail Brundin, from the Department of Italian, insisted that the future is collaborative; collaboration offers an immediate way out of the often closed-off worlds of our specialisms, fosters interdisciplinary exchanges and allows access to serious funding opportunities. She took issue with any idea that the initiative in pioneering new forms of academic writing should come from early-career academics; it is those who are safely tenured who have a responsibility to blaze a trail. Matthew Champion, a Research Fellow in History, drew attention to the care that has traditionally gone into the production of academic books—care over the quality of the finished product and over its physical appearance, down to details such as the font it is printed in. He wondered whether the move to digital and to a higher speed of publication would entail a kind of flattening of perspectives and an increased sense of alienation on all sides. Should we care if many people our work? Champion thought not: what we want is not 50,000 careless clicks but the sustained attention of deeply-engaged readers. Our third speaker, Liana Chua reported on the situation in Anthropology, where conservative publishing imperatives are being challenged by digital communications. Anthropologists usually write about living subjects, and increasingly those subjects are able to answer back.  This means that the ‘finished-product’ model of the book is starting to die off, with more fluid forms taking its place.Such forms (including film-making) are also better-suited to capturing the experience of fieldwork, which the book does a great deal to efface. Finally Orietta da Rold, from the Faculty of English, questioned the dominance of the book in academia. Digital projects that she had been involved in had been obliged, absurdly, to dress themselves up as books, with introductions and prefaces and conclusions. And collections of articles that might better be published as individual interventions were obliged to repackage themselves as books. The oppressive desire for the ‘big thing’ obscures the important work that is being done in a plethora of forms.

This means that the ‘finished-product’ model of the book is starting to die off, with more fluid forms taking its place.Such forms (including film-making) are also better-suited to capturing the experience of fieldwork, which the book does a great deal to efface. Finally Orietta da Rold, from the Faculty of English, questioned the dominance of the book in academia. Digital projects that she had been involved in had been obliged, absurdly, to dress themselves up as books, with introductions and prefaces and conclusions. And collections of articles that might better be published as individual interventions were obliged to repackage themselves as books. The oppressive desire for the ‘big thing’ obscures the important work that is being done in a plethora of forms.

In discussion it was suggested that the book form was a valuable identifier, allowing unusual objects like CD-ROMs or databases to be recognized and catalogued and found (the book, in this view, provides the metadata or the paratextual information that gives an artefact a place in the world). There was perhaps a division between those who saw the book as giving ideas a compelling physical presence and those who were worried about the versions of authority at stake in the monograph. The monograph model perhaps discourages people from talking back; this will inevitably come under pressure in a more ‘oral’ digital economy.

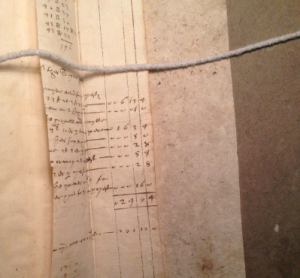

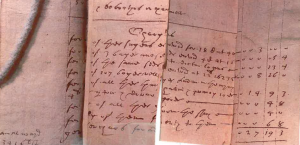

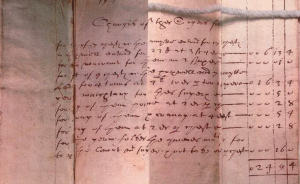

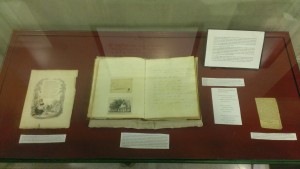

Our final ‘view’ of the day was ‘The View from Plurabelle Books’, offered by Michael Cahn but read in his absence by Gemma Savage. Plurabelle is a second-hand academic bookseller based in Cambridge; it was founded in 1996. Cahn’s talk focused on a different kind of ‘future’ of the academic book—the future in which the book ages and its owner dies. The books that may have marked out a mental universe need to be treated with appropriate respect and offered the chance of a new lease of life. Sometimes they carry with them a rich sense of their past histories.

A concluding discussion drew out several themes from the day:

(1) A particular concern had been where the impetus for change would and should come from—from individual academics, from funding bodies, or from government. The conservatism and two-sizes-fit-almost-all nature of the REF act as a brake on innovation and experiment, although the rising significance of ‘impact’ might allow these to re-enter by the back door. The fact that North America has remained impervious to many of the pressures that are affecting British academics was noted with interest.

(2) The pros and cons of peer review were a subject of discussion—was it the key to scholarly integrity or a highly unreliable form of gatekeeping that would naturally wither in an online environment?

(3) Questions of value were raised—what would determine academic value in an Open Access world? The day’s discussions had veered between notions of value/prestige that were based on numbers of readers and those that were not. Where is the appropriate balance?

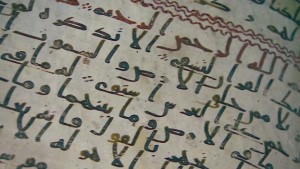

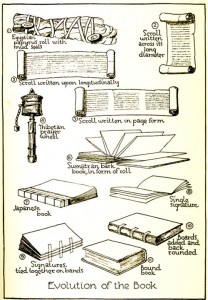

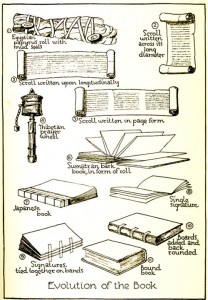

(4) A broad historical and technological question: are we entering a phase of perpetual change or do we expect that the digital domain will eventually slow down, developing protocols that seem as secure as those that we used to have for print? (And would that be a good or a bad thing?) Just as paper had to be engineered over centuries in order to become a reliable communications medium (or the basis for numerous media), so too the digital domain may take a long time to find any kind of settled form. It was also pointed out that the academic monograph as we know it today was a comparatively short-lived, post-World War II phenomenon.

(5) As befits a conference held under the aegis of the Centre for Material Texts, the physical form of the book was a matter of concern. Can lengthy digital books be made a pleasure to read? Can the book online ever substitute for the ‘theatres of memory’ that we have built in print? Is the very restrictiveness of print a source of strength?

(6) In the meantime, the one thing that all of the participants could agree on was that we will need to learn to live with (sometimes extreme) diversity.

With many thanks to our sponsors, Cambridge University Press, the Academic Book of the Future Project, and the Centre for Material Texts. The lead organizer of the day was Jason Scott-Warren (jes1003@cam.ac.uk); he was very grateful for the copious assistance of Sam Rayner, Rebecca Lyons, and Richard Fisher; for the help of the staff at the Pitt Building, where the colloquium took place; and for the contributions of all of our speakers.

Yesterday the CMT convened a one-day colloquium entitled ‘The Academic Book of the Future: Evolution or Revolution?’ This was part of Cambridge’s contribution to a host of events being held across the UK in celebration of the first ever Academic Book Week, which is itself an offshoot of the AHRC-funded ‘Academic Book of the Future’ project. The aim of that project is both to raise awareness of academic publishing and to explore how it might change in response to new digital technologies and changing academic cultures. We were delighted to have Samantha Rayner, the PI on the project, to introduce the event.

Yesterday the CMT convened a one-day colloquium entitled ‘The Academic Book of the Future: Evolution or Revolution?’ This was part of Cambridge’s contribution to a host of events being held across the UK in celebration of the first ever Academic Book Week, which is itself an offshoot of the AHRC-funded ‘Academic Book of the Future’ project. The aim of that project is both to raise awareness of academic publishing and to explore how it might change in response to new digital technologies and changing academic cultures. We were delighted to have Samantha Rayner, the PI on the project, to introduce the event.

This means that the ‘finished-product’ model of the book is starting to die off, with more fluid forms taking its place.Such forms (including film-making) are also better-suited to capturing the experience of fieldwork, which the book does a great deal to efface. Finally Orietta da Rold, from the Faculty of English, questioned the dominance of the book in academia. Digital projects that she had been involved in had been obliged, absurdly, to dress themselves up as books, with introductions and prefaces and conclusions. And collections of articles that might better be published as individual interventions were obliged to repackage themselves as books. The oppressive desire for the ‘big thing’ obscures the important work that is being done in a plethora of forms.

This means that the ‘finished-product’ model of the book is starting to die off, with more fluid forms taking its place.Such forms (including film-making) are also better-suited to capturing the experience of fieldwork, which the book does a great deal to efface. Finally Orietta da Rold, from the Faculty of English, questioned the dominance of the book in academia. Digital projects that she had been involved in had been obliged, absurdly, to dress themselves up as books, with introductions and prefaces and conclusions. And collections of articles that might better be published as individual interventions were obliged to repackage themselves as books. The oppressive desire for the ‘big thing’ obscures the important work that is being done in a plethora of forms.