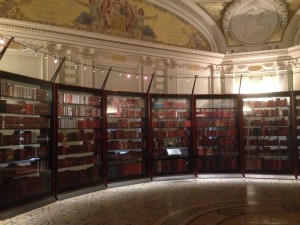

The Library of Congress is celebrating the two-hundredth anniversary of the acquisition of Thomas Jefferson’s 6,487-volume library by expanding their long-running exhibition Thomas Jefferson’s Library. Jefferson sold his library to Congress in 1815 to replace the collection lost to fire during the war of 1812. A second fire in 1851 destroyed nearly two-thirds of Jefferson’s volumes, and the present exhibition details the Library of Congress’s longstanding project to reassemble and reorder Jefferson’s library as it was first sold.

The Library of Congress is celebrating the two-hundredth anniversary of the acquisition of Thomas Jefferson’s 6,487-volume library by expanding their long-running exhibition Thomas Jefferson’s Library. Jefferson sold his library to Congress in 1815 to replace the collection lost to fire during the war of 1812. A second fire in 1851 destroyed nearly two-thirds of Jefferson’s volumes, and the present exhibition details the Library of Congress’s longstanding project to reassemble and reorder Jefferson’s library as it was first sold.

The books in the exhibition have been arranged by subject, following Jefferson’s own division of his books into History, Philosophy and Fine Arts. He followed Francis Bacon’s table of science (Memory, Reason, and Imagination) for this ordering, dividing his books into 44 ‘chapters’, beginning with Ancient History, Modern Europe, Modern France, and moving on to ‘Physical History’, which incorporates zoology, geology, and astronomy. His arrangement concludes with books on technical arts, which contained many topics new to the Congressional Library, including beekeeping, brewing, embroidery, and book-keeping.

The modern assemblers of the exhibition’s Jefferson library have further categorised his books, using coloured ribbons. A green ribbon marks books that were part of the original library, gold marks those which have recently been purchased for the project, and no ribbon is used for those which have been taken from the Library of Congress collection to fill gaps in the library. The ribbons highlight the transitional character of the library as it stands now, as well as its necessarily hybrid nature.

297 books remain to be found; white boxes mark their places on the shelves until they can be acquired. Lists of these books are currently circulating on the rare books market, but Jefferson’s preference for second editions and smaller, pocket-size editions mean that precise matches are hard to come by. However, selections of Jefferson’s surviving books are still being located, most recently in the Law Library of Congress and Washington University in St. Louis.

However, selections of Jefferson’s surviving books are still being located, most recently in the Law Library of Congress and Washington University in St. Louis.

Jefferson’s books are easily identifiable at least. Although there are very few instances of marginalia in his books, he regularly indicated his ownership of a volume in a unique way: by turning to the book’s ‘T’ signature, and inscribing a J alongside it, or by turning to ‘I’ and adding a T, he recorded his initials in the same location throughout his collection.

Out of the Ashes: A New Library for Congress and the Nation continues until May 2016, and the Thomas Jefferson’s Library exhibition is permanent.

Congratulations to Anne Toner, a member of the CMT steering committee since the Centre’s inception, on the publication of her book on Ellipsis in English Literature. As someone who is fascinated by the workings of punctuation, and who is seriously over-reliant on the ‘…’, I am looking forward to getting my hands on a copy…

Congratulations to Anne Toner, a member of the CMT steering committee since the Centre’s inception, on the publication of her book on Ellipsis in English Literature. As someone who is fascinated by the workings of punctuation, and who is seriously over-reliant on the ‘…’, I am looking forward to getting my hands on a copy…