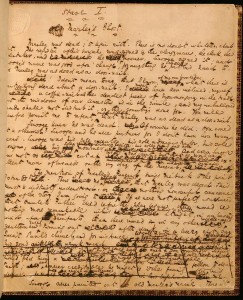

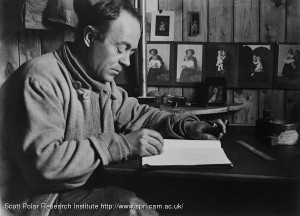

The Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge preserves many of the manuscript sources associated with British polar exploration, including journals, logbooks and correspondence. Some of these documents are on display at the recently renovated Polar Museum, based at the Institute, but the SPRI has also begun to make some material available online, beginning with Scott’s diary from his last ill-fated expedition to the South Pole in 1910-1912.

The Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge preserves many of the manuscript sources associated with British polar exploration, including journals, logbooks and correspondence. Some of these documents are on display at the recently renovated Polar Museum, based at the Institute, but the SPRI has also begun to make some material available online, beginning with Scott’s diary from his last ill-fated expedition to the South Pole in 1910-1912.

In his entry for Christmas Day in 1911, after making his usual notes on the weather conditions and the party’s progress, Scott writes of the feast the explorers enjoyed that night: ‘We had four courses. The first, pemmican, full whack, with slices of horse meat flavoured with onion and curry powder and thickened with biscuit; then an arrowroot, cocoa and biscuit hoosh sweetened; then a plum-pudding; then cocoa with raisins, and finally a dessert of caramels and ginger. After the feast it was difficult to move. Wilson and I couldn’t finish our share of plum-pudding. We have all slept splendidly and feel thoroughly warm – such is the effect of full feeding.’

For many, the text itself will not be unfamiliar – the diaries, gifted to the nation by Scott’s family, are in the British Library, and have appeared in many print editions since 1913. What makes this publication project different is the combination of different communication methods and media – using a linked blog, Twitter account, and photostreams to document the expedition day-by-day in this centenary year, the SPRI staff are hoping to see whether modern communication methods can provide a better understanding of the past. As the introduction to the project explains, ‘reading the journals over a few days is a very different experience from following the daily events of the expedition as they happen. It is hoped that the blog will enable readers to gain a deeper appreciation of the challenges faced by the expedition and the sacrifices made by Scott and his men. This is our first attempt to bring the diaries of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration to a worldwide audience by electronic means.’

The commemoration of a centenary, as for any anniversary, is about marking time, and so it is appropriate that this project particularly emphasises the dimension of time. Being given a daily excerpt from a document which is about the daily act of writing and recording is indeed very different from racing through a print edition at one’s own pace, and the online media of blogs and Twitter timelines allow this dimension to be explored in a new way.