Word gets about: Wrongdoing goes from strength to strength

November 6th, 2013Gallery; Jason Scott-WarrenIt has been amazing to see the interest provoked in academics and members of the general public by the material explored in the AHRC-funded project ‘Wrongdoing in Spain 1800-1936: Realities, Representations, Reactions’.

This second year of the project has been marked particularly by contact with a broader public arising from our exhibition, Read all about it! Wrongdoing in Spain and England in the long nineteenth century. The exhibition opened at the Milstein Exhibition Centre at the University Library on 29 April 2013. It runs until 23 December 2013, and is accompanied by a virtual exhibition. Digital facsimiles are also now available as part of the Cambridge Digital Library. This is the first time a virtual exhibition at the UL has run alongside the physical one, and it will remain accessible to the public after the closing date of the physical exhibition. The virtual material includes extra items, and provides translations of the (lengthy) titles of the Spanish examples. Both in the mounting of the virtual exhibition and in applying OCR (Optical Character Recognition) to the digitized texts, our project has been a pilot-scheme for the UL’s digital team.

This second year of the project has been marked particularly by contact with a broader public arising from our exhibition, Read all about it! Wrongdoing in Spain and England in the long nineteenth century. The exhibition opened at the Milstein Exhibition Centre at the University Library on 29 April 2013. It runs until 23 December 2013, and is accompanied by a virtual exhibition. Digital facsimiles are also now available as part of the Cambridge Digital Library. This is the first time a virtual exhibition at the UL has run alongside the physical one, and it will remain accessible to the public after the closing date of the physical exhibition. The virtual material includes extra items, and provides translations of the (lengthy) titles of the Spanish examples. Both in the mounting of the virtual exhibition and in applying OCR (Optical Character Recognition) to the digitized texts, our project has been a pilot-scheme for the UL’s digital team.

Assembling the exhibition was a major enterprise, and for those who have never done one, let us warn you that it is fascinating, time-consuming and calls on a whole range of new skill-sets. We were in the capable hands of Emily Dourish from the UL. Alison Sinclair (PI of the Wrongdoing project) selected and curated the Spanish material while Vanessa Lacey (the librarian who had been in charge of cataloguing the thousands of items consigned to the UL’s Tower) did the same with the English material, and we were supported by Liam Sims. For the Spanish examples we drew on the 2000 pliegos sueltos (chap-books) being digitised and catalogued for the Wrongdoing project, and for the English we drew on the more than 200,000 items of ‘secondary’ (i.e. ‘non-serious’) material in the UL that had been catalogued thanks to money from the Mellon Foundation.

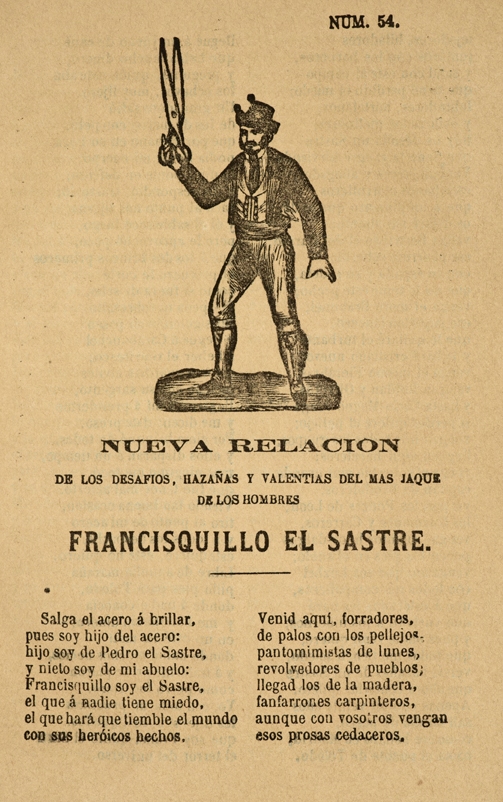

Various things became clear as we worked towards the exhibition itself. There was enthusiasm across the board for our material, whether from the design team who worked on publicity and the layout, or from the UL admissions staff (who see the exhibition all the time); and there was bonding as we voted for Francisquillo el Sastre to be the central icon (he was thereafter known as ‘Scissorman’ for reasons that are apparent from our publicity). A background in doing Sudoku might have been a help for the two curators (and it was the pastime of neither). There were hurdles. Not all material could be exhibited, as it had to pass first under the eagle-eyes of the staff of the Conservation unit; many of the Spanish items were bound together in volumes, sometimes rather tightly, so that it was a challenge to select which item, out of more than a hundred items in a volume, should be put on display; directly comparable material was not always available for the two countries involved. We decided on a life-trajectory as the ‘narrative’ of the exhibition. Thus it begins with ‘Knowing right from wrong’, moves through the teenage years (daughters are singled out more than sons for being wayward) and family frictions, then into more and more extreme and monstrous examples of wrongdoing, with the final pillar in the exhibition being devoted to retribution and various forms of execution.

One of the further procedures we will be applying to our digitized material is that of optical character recognition, which will allow for searches according to words or phrases. This will contribute enormously to our knowledge of the activity of printers, for example, and in mapping the occurrence of particular types of wrongdoing. It should be noted, however, that you cannot always find varieties of wrongdoing according to their official name. ‘Rape’ (‘violación’) almost never occurs, and this wrongdoing has to be tracked through a variety of circumlocutions, some of which refer to honour, others to flowers that have been made to wither…

One of the further procedures we will be applying to our digitized material is that of optical character recognition, which will allow for searches according to words or phrases. This will contribute enormously to our knowledge of the activity of printers, for example, and in mapping the occurrence of particular types of wrongdoing. It should be noted, however, that you cannot always find varieties of wrongdoing according to their official name. ‘Rape’ (‘violación’) almost never occurs, and this wrongdoing has to be tracked through a variety of circumlocutions, some of which refer to honour, others to flowers that have been made to wither…

The general public has come and been enthusiastic (the comments book attests strongly to this). To the end of October 2013 there were 23,880 visits to the exhibition, of which 17,130 were after 1 July. Over this period the virtual exhibition had 6,307 hits to the site from 4,456 unique visitors. The youngest visitors included ten-year olds from a primary school in Hackney, and there were some even younger at the quiz session we ran on the exhibition at the Festival of Ideas on 26 October. Talks in Cambridge and elsewhere have fielded an even wider age-range, one group almost all in their nineties. All have come up with perceptive comments and insights, not least on the relevance of street-literature of the nineteenth century to modern issues of wrongdoing, law and order and to issues of education or delinquency.

No less enthusiastic has been the response of academic audiences, even though at times, when one was addressing audiences in Spain, it felt as though news of our collection of sueltos might have provoked thoughts of the Elgin marbles. Contact with new material could come quite randomly. Discussion with an emeritus colleague in London about Goya led to his giving an excellent collection of sueltos to the UL. A visit to a municipal library in Toledo coincided with an exhibition there of aleluyas, the poster-sized sheets of 48 illustrations and accompanying text in couplets. It included some rare examples, and put the PI of the Wrongdoing project onto another large collection.

Colleagues in Spain in fact are keen to work further with our collection, and to find ways of linking collections. Yet more exciting is the prospect of mounting a wide-reaching research project that could work comparatively with the street-literature of several countries.

An online exhibition, via Facebook, is planned for launching at the British Library in Spring 2014. We are able to draw on somewhat different material there, including publications on prisons (and prison-life) and various turn-of-the-century novels which mix modernity with an invitation to be fascinated, or even seduced, by wrongdoing.