On 10-11 September 2018, around 65 scholars from around the world converged on the Faculty of English for a CMT conference entitled Paper-Stuff: Materiality, Technology and Invention. Premised on the suspicion that paper as a substance is so ubiquitous that we can no longer bring it fully into view, the conference ranged widely across time and space, seeking to unmask the often hidden work of paper-stuff in sustaining human cultures.

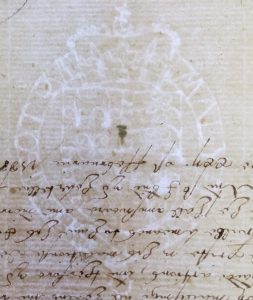

The conference opened with a plenary panel on the diplomatic and bureaucratic uses of paper in the early modern period, emphasising the global reach of the medium. Megan Williams initiated proceedings by exploring the burgeoning place of paper in Renaissance diplomacy, paying particular attention to the way that ambassadors expanded their reports in order to solidify their reputations for diligence and their claims for payment, and also noting how paper allowed for multiple additions and annotations to be made to a document as it crossed various desks on its journey to the archive. Frank Birkenholz followed this up by exploring the role of paper in the global trade networks of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The Company’s chief anxiety seems to have been the preservation of information, which it achieved partly by creating multiple copies (turning transcription into a full-time job) and partly by seeking solutions to the spoliation of archives, whether at sea or in its warehouses, where infestations of white ants were commonplace.Alison Wiggins rounded off the session by looking at the occurrences of paper in the seventeenth-century accounts of the Cavendish family. Paying attention to the variety of different grades of paper that were deployed for writing, wrapping and coverage, Wiggins concluded with a visit to the ‘evidence room’ that formed the heart of the information management system at Hardwick Hall. This working archive took on an increasingly global reach as the Cavendishes began to invest in the VOC and other colonial ventures.

The conference opened with a plenary panel on the diplomatic and bureaucratic uses of paper in the early modern period, emphasising the global reach of the medium. Megan Williams initiated proceedings by exploring the burgeoning place of paper in Renaissance diplomacy, paying particular attention to the way that ambassadors expanded their reports in order to solidify their reputations for diligence and their claims for payment, and also noting how paper allowed for multiple additions and annotations to be made to a document as it crossed various desks on its journey to the archive. Frank Birkenholz followed this up by exploring the role of paper in the global trade networks of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The Company’s chief anxiety seems to have been the preservation of information, which it achieved partly by creating multiple copies (turning transcription into a full-time job) and partly by seeking solutions to the spoliation of archives, whether at sea or in its warehouses, where infestations of white ants were commonplace.Alison Wiggins rounded off the session by looking at the occurrences of paper in the seventeenth-century accounts of the Cavendish family. Paying attention to the variety of different grades of paper that were deployed for writing, wrapping and coverage, Wiggins concluded with a visit to the ‘evidence room’ that formed the heart of the information management system at Hardwick Hall. This working archive took on an increasingly global reach as the Cavendishes began to invest in the VOC and other colonial ventures.

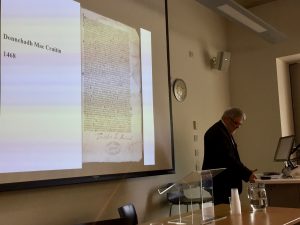

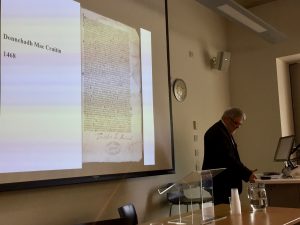

Our first plenary paper was given by Pádraig Ó Macháin, and focused on the transition from vellum to paper in Gaelic manuscripts. This was also a transition in the mode of production, shifting away from a world in which manuscripts were produced in monastic scriptoria and towards a more commercialised world with a starker division of labour between authors, scribes, booksellers and readers. The transition occurred around 1600, but Ó Macháin posited a 100-year crossover period in which manuscripts combined vellum and paper in unpredictable ways. Comparing the points of transition in surviving civic records and in private manuscripts, he pointed to the significance of professional bureaucrats in promoting the spread of paper; and he emphasised the value of Gaelic sources, with their highly informative colophons, in allowing us to track the process of transition to paper.

Our first plenary paper was given by Pádraig Ó Macháin, and focused on the transition from vellum to paper in Gaelic manuscripts. This was also a transition in the mode of production, shifting away from a world in which manuscripts were produced in monastic scriptoria and towards a more commercialised world with a starker division of labour between authors, scribes, booksellers and readers. The transition occurred around 1600, but Ó Macháin posited a 100-year crossover period in which manuscripts combined vellum and paper in unpredictable ways. Comparing the points of transition in surviving civic records and in private manuscripts, he pointed to the significance of professional bureaucrats in promoting the spread of paper; and he emphasised the value of Gaelic sources, with their highly informative colophons, in allowing us to track the process of transition to paper.

After lunch there were two sets of parallel sessions. A session on ‘the coming of paper’ was opened by Jesse Lynch, who investigated the early evidence for paper in Britain through the early paper documents in the Exeter diocesan archives, cross-comparing documents in the National Archives coming from the Angevin territories and elsewhere. He argued for a ‘punctuated equilibrium’ according to which writing practices changed at different rates in different places, due to largely adventitious circumstances. Paul Schweitzer-Martin followed this up by considering changes in the consumption and usage of paper in the transition to print. Addressing questions of standardization and differentiation, and working through the sources and statistical approaches that might tell us about degrees of increase in the need for paper, he admitted that the transition to print may have been evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Hannah Ryley’s paper focused on late-medieval manuscripts that mix paper with parchment, often in discernible patterns that would have required considerable labour to engineer. What does paper do to parchment and parchment to paper in these unexpected material combinations? Such mixings of different substrates were partly aimed at protecting and strengthening the book, but further work will be needed to fully unravel the motives at work.

A session on ‘paper bodies’ began with a lecture performance by Sophie Seita. Dressing up in paper clothes, Seita channelled the spirits of Margaret Cavendish, Denis Diderot, Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle and the it-narrative in order to challenge what Sara Ahmed has called ‘the fantasy of a paperless philosophy’. Along the way, Seita brought paper forcefully back into view in its role as a legitimating device—not least in the academic world, where the production of ‘papers’ serves an alarmingly similar purpose to the production of papers at a customs office. Karen Sandhu, a book artist, offered a meditation on the irritating or irritated book, drawing on Gertrude Stein’s dictum that ‘one of the definitions of modern art is that it be irritating’. Accordingly, she described her own project to incorporate a number of allergens into the paper of a book that might genuinely get under its reader’s skin. Anna Reynolds considered interactions between books and bodies in the early modern period, when the deterioration of paper over time was read as a mirror to the wasting of skin. In her account, early modern paper would have been characterised above all by its greasiness, whether that grease came from the flax that made the clothes that made the rags that made the paper, or whether it came from the fingers of users. Taken together the three papers offered a compelling insight into just how visceral the experience of paper might be.

A session on ‘paper bodies’ began with a lecture performance by Sophie Seita. Dressing up in paper clothes, Seita channelled the spirits of Margaret Cavendish, Denis Diderot, Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle and the it-narrative in order to challenge what Sara Ahmed has called ‘the fantasy of a paperless philosophy’. Along the way, Seita brought paper forcefully back into view in its role as a legitimating device—not least in the academic world, where the production of ‘papers’ serves an alarmingly similar purpose to the production of papers at a customs office. Karen Sandhu, a book artist, offered a meditation on the irritating or irritated book, drawing on Gertrude Stein’s dictum that ‘one of the definitions of modern art is that it be irritating’. Accordingly, she described her own project to incorporate a number of allergens into the paper of a book that might genuinely get under its reader’s skin. Anna Reynolds considered interactions between books and bodies in the early modern period, when the deterioration of paper over time was read as a mirror to the wasting of skin. In her account, early modern paper would have been characterised above all by its greasiness, whether that grease came from the flax that made the clothes that made the rags that made the paper, or whether it came from the fingers of users. Taken together the three papers offered a compelling insight into just how visceral the experience of paper might be.

After a coffee break, the programme continued with a session on ‘transmediations’. Tom White initiated proceedings by considering the question of surface in manuscripts, taking as an example a single folio of the Glastonbury Miscellany, Trinity College, Cambridge, MS O.9.38. Thinking about the fate of the folio across the whole of the manuscript’s history, from its initial creation to its modern restoration and digitisation, White revealed it as a resolutely polychronic artefact, in which medieval and early modern paper ecologies are entangled with modern archival technologies. At the same time he argued for the heuristic value of attending to the seemingly blank page. Thinking about an entirely different set of paper transformation, Geoffrey Day transported us to the underworld of eighteenth-century London. Drawing on a variety of legal and business records, he reconstructed the period’s sizeable black-market in stolen paper. The growth of retail industries created a massive demand for wrapping paper which was satisfied through complex and highly risky criminal operations, some of them involving the theft of printed sheets intended for works such as Johnson’s Dictionary andLives of the Poets.

The parallel session, on ‘the end of paper’, opened with Joseph Elkanah Rosenberg’s ‘Paper Bombs’, focused on the Second World War. Prefacing his talk with Mallarmé’s dictum that ‘there is no explosion but a book’, Rosenberg began by unpicking the celebrated photograph of Holland House library after a bombing—in his account, a highly staged image that aimed to send out the clear message that barbaric fascists bomb books while democratic Britons read them. But Rosenberg then pointed out that the various genteel readers in the image could equally well be read as scavengers, gathering paper for recycling in to cartridge and shell cases or mortar carriers as part of the war effort. Saving and salvaging, memorialising and forgetting, turn out to be closely intertwined. Chris Wrycraft carried forward the military theme, looking at the way that writers were forced to move away from printed publications and towards radio broadcasts thanks to the paper shortages of World War II. At the heart of his account were the radio scripts of George Orwell, their every word monitored in advance by overseers at the BBC. As in the East India Company, so in the BBC, paper allowed changes to be plentifully tracked in the margins and facilitated multiple copying (everything that went out over the airwaves had to be cross-copied between six and fifteen times). Finally in this session Louisa Shen pulled our gaze towards the future and the ever-receding prospect of paperlessness. Locating paper’s superiority to the screen partly in its tolerance of unprescribed, idiosyncratic inputs and partly in its openness to palimpsestic imprinting, Shen examined some of our current sci-fi fantasies about future improvements on the screen. Might we become screenless before we become paperless?

The parallel session, on ‘the end of paper’, opened with Joseph Elkanah Rosenberg’s ‘Paper Bombs’, focused on the Second World War. Prefacing his talk with Mallarmé’s dictum that ‘there is no explosion but a book’, Rosenberg began by unpicking the celebrated photograph of Holland House library after a bombing—in his account, a highly staged image that aimed to send out the clear message that barbaric fascists bomb books while democratic Britons read them. But Rosenberg then pointed out that the various genteel readers in the image could equally well be read as scavengers, gathering paper for recycling in to cartridge and shell cases or mortar carriers as part of the war effort. Saving and salvaging, memorialising and forgetting, turn out to be closely intertwined. Chris Wrycraft carried forward the military theme, looking at the way that writers were forced to move away from printed publications and towards radio broadcasts thanks to the paper shortages of World War II. At the heart of his account were the radio scripts of George Orwell, their every word monitored in advance by overseers at the BBC. As in the East India Company, so in the BBC, paper allowed changes to be plentifully tracked in the margins and facilitated multiple copying (everything that went out over the airwaves had to be cross-copied between six and fifteen times). Finally in this session Louisa Shen pulled our gaze towards the future and the ever-receding prospect of paperlessness. Locating paper’s superiority to the screen partly in its tolerance of unprescribed, idiosyncratic inputs and partly in its openness to palimpsestic imprinting, Shen examined some of our current sci-fi fantasies about future improvements on the screen. Might we become screenless before we become paperless?

Day 2 kicked off with parallel sessions pitting ‘Engineering with Paper’ against ‘Paper Technology’. In the former, Agnieszka Helman-Wašny reviewed the earliest history of paper, emphasising the impossibility of disentangling truth from myth. Origin stories tend to give precise dates for paper’s creation and its transmisison to the West, but such stories probably paper over a much complex and multiple reality. Despite a longstanding ban on the archaeological investigation of much early paper (the Chinese state has decreed that the question of its origins is settled), fibre analysis of available samples is complicating the standard picture, suggesting that rag and bark may have cohabited from the very beginning, as did laid (strained through a frame) and woven (strained through fabric). Bruce Huett kept our gaze on the Himalayas but moved to the modern world, looking at the efforts to revive traditional papermaking in the twentieth and twenty-first century. Swamped by the advent of industrial paper by the 1950s, craft skills were revived from the 1970s as part of the effort to preserve local cultural heritage and to alleviate poverty. Such programmes have enjoyed very mixed success, but they have helped to propagate papers that are distinctively durable, good for calligraphy and naturally resistant to insects. Yasmin Faghihi took us ‘From China to Italy’, exploring how the dissemination of paper went alongside the development of Islamic scripts, and how Islamic paper, finely burnished to facilitate the gliding of the reed pen, served as a vital stage in the transition to modern European papers. She concluded with images of Italian papers made for the Islamic market, as found in fourteenth-century Arabic manuscripts.

Day 2 kicked off with parallel sessions pitting ‘Engineering with Paper’ against ‘Paper Technology’. In the former, Agnieszka Helman-Wašny reviewed the earliest history of paper, emphasising the impossibility of disentangling truth from myth. Origin stories tend to give precise dates for paper’s creation and its transmisison to the West, but such stories probably paper over a much complex and multiple reality. Despite a longstanding ban on the archaeological investigation of much early paper (the Chinese state has decreed that the question of its origins is settled), fibre analysis of available samples is complicating the standard picture, suggesting that rag and bark may have cohabited from the very beginning, as did laid (strained through a frame) and woven (strained through fabric). Bruce Huett kept our gaze on the Himalayas but moved to the modern world, looking at the efforts to revive traditional papermaking in the twentieth and twenty-first century. Swamped by the advent of industrial paper by the 1950s, craft skills were revived from the 1970s as part of the effort to preserve local cultural heritage and to alleviate poverty. Such programmes have enjoyed very mixed success, but they have helped to propagate papers that are distinctively durable, good for calligraphy and naturally resistant to insects. Yasmin Faghihi took us ‘From China to Italy’, exploring how the dissemination of paper went alongside the development of Islamic scripts, and how Islamic paper, finely burnished to facilitate the gliding of the reed pen, served as a vital stage in the transition to modern European papers. She concluded with images of Italian papers made for the Islamic market, as found in fourteenth-century Arabic manuscripts.

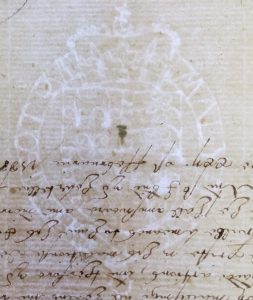

In ‘Paper Technology’, Orietta Da Rold and Ed Potten discussed the early steps in watermark studies in Britain, remarking on W.Y. Ottley’s precocious finding in the field. Anticipating many other nineteenth century filigranologists, Ottley collected four albums of watermarks with indexes in the 1830s, now Cambridge University Library, Add. MS 2878, which are now very little known by scholars. Richard Beadle followed up by presenting another CUL gem, Add. MS 4124, an unusual blank book that was bound in Winchester at the end of the fifteenth century. This manuscript has eluded the attention of scholars because of later, sixteenth-century jottings on some of the pages, but it was actually put together in or around the 1480s. Pointing out that very few such books survive from the period, Beadle pondered the question of its function: was it intended for monastic, legal, or administrative use? The jury is still out! Neil Harris concluded this session by presenting a fascinating new project that will follow the footsteps of the Charles-Moïse Briquet, the author of the magisterial index of watermarks entitled Les filigranes (1907), across the archives of Europe. Reconstructing the daily research routines that Briquet adopted during a visit to the medieval archive of the city of Udine, Harris impressed on the audience just how quickly Briquet could work, looking at hundreds of sheets in a day. The project aims to digitise all of the documents that he consulted during his heroic travels—a process which will also enable the patterns of twinning in the watermarks he recorded to be documented for the first time. This is a resource that anyone who has worked with Briquet’s magisterial volumes will look forward to using.

Our second plenary paper was less a talk than a practical workshop, in which paper-artist Linda Toigo offered to teach us ‘how to rip a book and not feel guilty’. Toigo began by talking us through some of her own dazzling bibliographical creations, in which she uses a surgical scalpel and sharp wit to give a new lease of life to previously unloved volumes. Having shown us one of her magnificent pop-up books, Toigo then invited delegates to make their own pop-up pages, using leaves torn unceremoniously from some mouldering hardbacks. The air of quiet concentration that filled the room as brain-work made way for physical cutting-and-pasting was palpable. The session provided a reminder of the physical resilience of paper, which has innumerable ways of surviving in destruction, and of seeming to draw energy from efforts to destroy it.

Our second plenary paper was less a talk than a practical workshop, in which paper-artist Linda Toigo offered to teach us ‘how to rip a book and not feel guilty’. Toigo began by talking us through some of her own dazzling bibliographical creations, in which she uses a surgical scalpel and sharp wit to give a new lease of life to previously unloved volumes. Having shown us one of her magnificent pop-up books, Toigo then invited delegates to make their own pop-up pages, using leaves torn unceremoniously from some mouldering hardbacks. The air of quiet concentration that filled the room as brain-work made way for physical cutting-and-pasting was palpable. The session provided a reminder of the physical resilience of paper, which has innumerable ways of surviving in destruction, and of seeming to draw energy from efforts to destroy it.

The conference concluded with two last parallel sessions. In the first, on ‘paper analysis’, Goran Proot initiated his audience into the little-known history of the thickness of paper as it evolved over time. On the basis of his quantitative research, he was able to show that octavos were usually made with a thinner paper stock than larger books such as folios. This discovery constitutes a valuable contribution to the ongoing discussion of the significance of book formats, since it suggests that the format of a book was already foreseen when paper was acquired. Next Maria Stieglecker introduced the Wasserzeichen Project (https://www.wasserzeichen-online.de) to catalogue German medieval watermarks, showing how mapping the paper manuscripts of Johannes von Speyr could give important clues as to where and when he did his copying. This was a talk that showed how much could be achieved by the painstaking collection of information about paper stocks; it was fascinating to see how the ‘distant reading’ of watermarks could be used to map the movements of people and texts. Anne Mailloux reported back on fifteeen years of comparably fine-grained work on paper used in thirteenth century Provence. Her research, taking the 1331-4 registers of Leopardo da Foligno as its central focus, enabled her to document the dissemination of different paper types across the Mediterranean. Emanuela di Stefano argued that claims for the primacy of Fabriano as a centre of medieval paper production might be overstated, and suggesting that another town in the Marche, Pioraco, was worthy of equal consideration. Drawing on the mercantile records of the Datini family of Prato, she stressed the technological innovation of ‘bombazine paper’, which was much more flexible and resistant than its Arabic rivals, and explored the extraordinary diffusion of Italian paper across late medieval and early modern Europe.

Parallel with this was a session on ‘paper inventions’, initiated with Elizabeth Deane Romariz’s analysis of the neglected phenomenon of the architect’s notebook. Focusing on two examples, one kept by John Webb in the middle of the seventeenth-century, the other by Nicholas Hawksmoor from the 1680s to the 1710s, Romariz called attention to the intimacy and functionality of these pocket-sized volumes, which allowed their owners to exercise control over the complex process of planning and creating a building. Boris Jardine took us into another sphere of early modern technical know-how, describing his pursuit of a peculiar subset of prints that were created by putting a mathematical/astronomical instrument through a rolling press. In 1997 only two examples of the genre were known, but many new examples have recently come to light. As well as setting up an intriguing kind of relationship between image and archetype, they testify to the fascination of virtuosi with the seemingly impossible precision of the new astrolabes, quadrants and sundials.  Gill Partington explored a very different kind of knowledge transaction, discussing the artist John Latham’s unusual dealings with a library copy of Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture(these involved masticating the pages of the book and creating a distillation—later duly labelled and returned to the library—from the remnants. Linking Latham’s with other bibliographical and biblioclastic artworks, Partington suggested that they raise important questions about where the essence of the book lies. Heather Wolfe rounded things off by discussing the activities of John Spilman, a High German who received a patent to make paper at a mill near Dartford in 1589. Tracing Spilman’s activities through the published literature, Wolfe initially encountered much assertion but little solid evidence. When she headed into the archives, however, she discovered that in the period following the Armada victory, many of the great officers of state were to be found scribbling missives on home-grown paper, watermarked with the royal arms, that was undercutting the familiar ‘pot-paper’ imported from Normandy. Here, perhaps, are the beginnings of a paper history for the Brexit age.

Gill Partington explored a very different kind of knowledge transaction, discussing the artist John Latham’s unusual dealings with a library copy of Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture(these involved masticating the pages of the book and creating a distillation—later duly labelled and returned to the library—from the remnants. Linking Latham’s with other bibliographical and biblioclastic artworks, Partington suggested that they raise important questions about where the essence of the book lies. Heather Wolfe rounded things off by discussing the activities of John Spilman, a High German who received a patent to make paper at a mill near Dartford in 1589. Tracing Spilman’s activities through the published literature, Wolfe initially encountered much assertion but little solid evidence. When she headed into the archives, however, she discovered that in the period following the Armada victory, many of the great officers of state were to be found scribbling missives on home-grown paper, watermarked with the royal arms, that was undercutting the familiar ‘pot-paper’ imported from Normandy. Here, perhaps, are the beginnings of a paper history for the Brexit age.

The conference was organised by Orietta Da Rold and Jason Scott-Warren, with Carlotta Barranu as administrator and Marica Lopez Diaz providing invaluable assistance behind the scenes. It was funded by the British Academy as part of Dr Da Rold’s project ‘Paper in Late Medieval English Manuscript Culture from 1300 to 1475’, with graduate bursaries generously sponsored by AMARC, and further funding from the Faculty of English and the Centre for Material Texts.

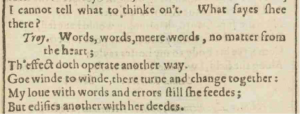

There are a few moments in Shakespeare that capture these aspects of paper. Amid the utter bleakness of the ending of Troilus and Cressida, Troilus receives a letter from Cressida. We never find out what it says; Troilus dismisses the contents as ‘words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart’, before tearing it up. ‘Goe wind to wind, there turn and change together’. The fluttering of the paper becomes a visual metaphor for what Troilus perceives to be his beloved’s faithlessness.

There are a few moments in Shakespeare that capture these aspects of paper. Amid the utter bleakness of the ending of Troilus and Cressida, Troilus receives a letter from Cressida. We never find out what it says; Troilus dismisses the contents as ‘words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart’, before tearing it up. ‘Goe wind to wind, there turn and change together’. The fluttering of the paper becomes a visual metaphor for what Troilus perceives to be his beloved’s faithlessness.