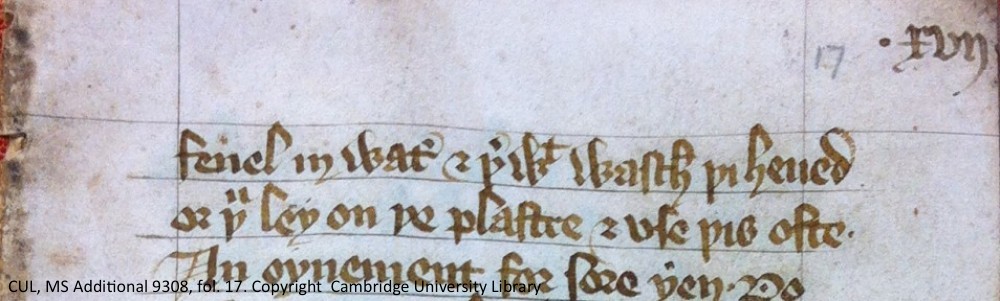

How different would studying medieval manuscripts be if we could interact with these books like their earliest readers did? Anxieties about how the digital realm structures relations between people and things, both in medieval studies and beyond, give an urgency to this thought experiment. Books, of course, weren’t (and aren’t) just read: they are experienced through the senses, they are made to occupy certain spaces, they exchange hands, they invite interventions that promise to speak to future readers. Their ‘thing power’ is predicated on a tangibility and mobility that threaten to make way in the two dimensions of the digital image. Medievalists often emphasise the acoustic, tactile, and even olfactory qualities of handling parchment. These are sensations that can be approximated, though not fully replicated, in the reading room. There is, however, a set of more corporeal, even ‘dirty’, reading practices that can only be imagined in relation to these heritage objects. A twenty-first-century reader rubbing, scratching, stroking, or kissing a manuscript illumination doesn’t bear thinking about!

Or does it? Kathryn M. Rudy’s ground-breaking research on the traces of tactile interaction left on medieval books has shown, firstly, how pervasive such practices were, and secondly, how they point to a reader’s, or community of readers’, affectively-charged attachment to a text or image and what it represents or embodies. My postdoctoral project, funded by the British Academy and hosted by the MMLL Faculty in Cambridge, considers the stakes of these haptic practices for manuscripts written in medieval French. How do we read these signs of touch? How do we read with these signs of touch?

Continue reading