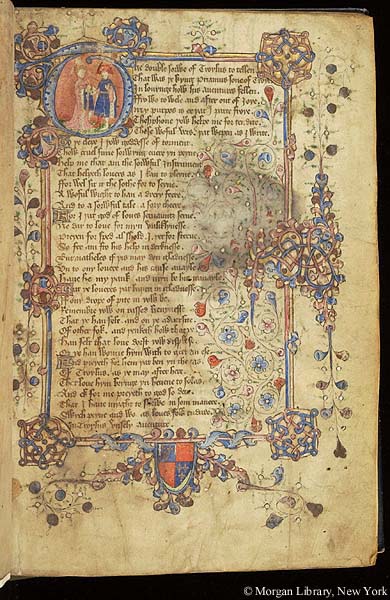

Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde focuses its narrative tension through paper: the material itself is essential to the plot of the poem. Troilus both confesses his admiration for Criseyde and later expresses his anxiety about her fidelity through his correspondence. Pandarus’s entire identity is encapsulated by his role as the mediator of these paper communications. Criseyde’s eventual betrayal of Troilus is heralded by her neglect of paper in answering Troilus’s missives. Most striking about paper in this poem, however, is the fact that it is an anachronistic technology at the center of a ‘Troy’ where Martha Rust intriguingly notes that clay tablets would have been in use.[1] Where Orietta Da Rold highlights Chaucer’s deliberate attention to paper itself as a material that underscores both plot and character development while making visible—and tangible—that plot’s most visceral themes,[2] paper is clearly too pivotal for its anachronistic presence to be incidental. This invites the following question: in centering this anachronistic technology, does Troilus and Criseydeinvite further anachronistic engagement?

Continue reading