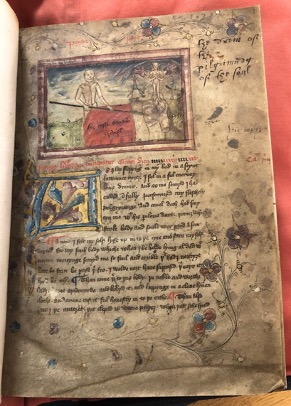

MS Kk.1.7 contains The Pilgrimage of the Soul – the Middle English adaptation of Guillaume de Deguilleville’s fourteenth-century poem Le Pèlerinage de l’Âme. All of the extant manuscript copies of the Soul reserve space for illustration, indicating that miniatures played an integral role in the manuscript tradition of the Soul. Close comparison of the scenes chosen for illustration reveals an archetypal programme of illustration. Most copies show preparation or completion of twenty-six scenes, and these scenes show a high degree of consistency in subject and, often, iconography.[i] In Kk.1.7, a total of seventeen scenes are illustrated, and possibly one or two others are missing due to loss. The illustrator made critical decisions not only about which moments of the narrative would receive greater emphasis, but also about the iconography of these scenes, thereby deciding how they were presented and constructing reader responses.