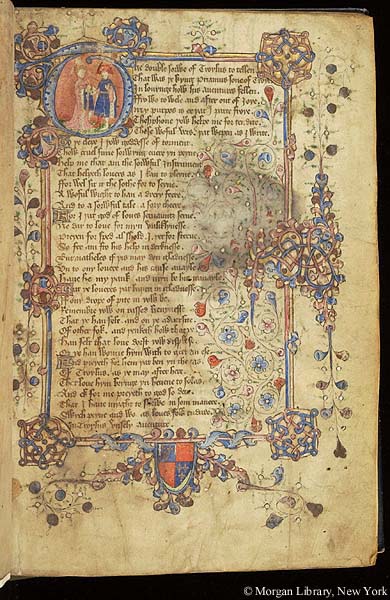

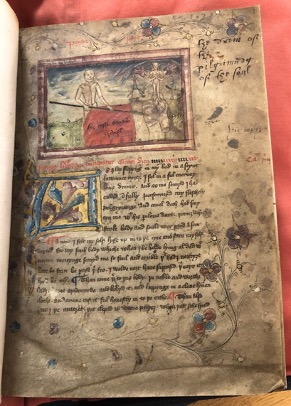

What can we learn from practice-led approaches to medieval codicology? Before pursuing my graduate studies in medieval literature, I trained as an illuminator. Over the course of a year, I took practical courses in gilding, pigment-making, and Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and later medieval styles of illumination at the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London. I now work primarily with gold on vellum, coupled with traditional pigments and foraged inks, to create both reproductions of medieval designs and original pieces. My undergraduate studies had already inspired a keen interest in the medieval material text, and it was always the illuminated manuscripts that would catch my eye, with their ability to capture and manipulate the subtle interactions between light, metal, and parchment. It therefore seemed a natural step to learn more about the practical side of the production and decoration of medieval books. I am now academically trained as a medievalist; working with manuscripts on a regular basis, I thus bridge two seemingly overlapping but still quite distinct fields.

Experiential and artistic knowledge of the processes and materials of illumination is very rarely applied to formal academic study. There have been two wonderful collaborations that use the practices of modern working scribes as tools for historical research: that of Patricia Lovett and Michelle Brown, and of Patrick Conner and Cheryl Jacobsen, both of which focus primarily on palaeography and script.[1] I was recently able to take part in a similar collaboration with postdoctoral researcher, Henry Ravenhall, but in our case, with a focus on gold, ink, and pigment in manuscript miniatures. Henry’s work explores the evidence of tactile interactions between readers and their books, and, in particular, instances in which images have been visibly (and often forcibly) erased. Faced with the obvious problem of not being able to test Henry’s hypotheses on actual medieval manuscripts, we decided to put my illumination training to experimental and destructive use, and create a mock-up miniature to rub out.

Continue reading