MS Kk.1.7 contains The Pilgrimage of the Soul – the Middle English adaptation of Guillaume de Deguilleville’s fourteenth-century poem Le Pèlerinage de l’Âme. All of the extant manuscript copies of the Soul reserve space for illustration, indicating that miniatures played an integral role in the manuscript tradition of the Soul. Close comparison of the scenes chosen for illustration reveals an archetypal programme of illustration. Most copies show preparation or completion of twenty-six scenes, and these scenes show a high degree of consistency in subject and, often, iconography.[i] In Kk.1.7, a total of seventeen scenes are illustrated, and possibly one or two others are missing due to loss. The illustrator made critical decisions not only about which moments of the narrative would receive greater emphasis, but also about the iconography of these scenes, thereby deciding how they were presented and constructing reader responses.

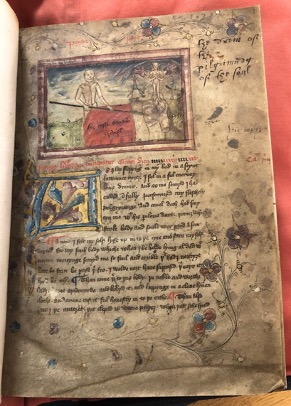

Much of the variation in Kk.1.7 might perhaps be attributed to the strong associations of the illustrated scenes with visual iconography, as seen in medieval pictorial representation and also in medieval drama.[ii] Rather than offering a faithful representation of the text, many of the miniatures rely on conventional pictorial prototypes and draw on extratextual traditions. The first illustration depicts the figure of Death piercing the sleeper with a spear, while the naked soul with hands in prayer is lifted up from his sleeping body into the clouds by the hands of God (fol. 1r). The motif of the departing soul with hands in prayer being carried into the heavens was popular between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, particularly in the prominent Ars moriendi tradition, which was heavily illustrated in England.[iii]

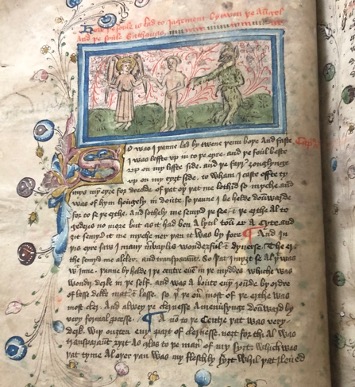

The angel and devil then lead the soul to judgement, and the soul is placed between them in the composition (fol. 3v), which recalls common medieval representations of the allegorical battle between good and evil, as illustrated fully in The Castle of Perseverance, a morality play of the early fifteenth century that visually ‘stages’ the division between a good advisor and an evil advisor.[iv]

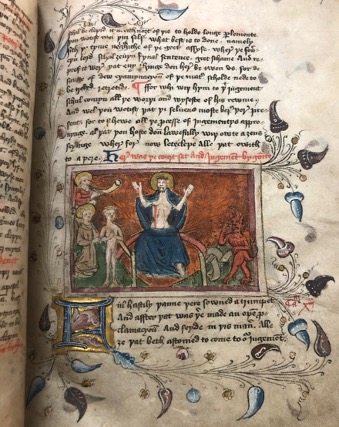

The third miniature, on fol. 7r, is the presentation of the soul for judgement, and the proceedings are to be presided over by archangel Michael, as he ‘hast promyss’ to the ‘souerayn king to do iustyce and | ȝeue iugement to all maner of peple’ (lines 16, 17-18 on fol. 4v). However, Michael is not depicted.

The illustrator adopts the authoritative tradition of Christ as Judge, figured as a Man of Sorrows, one of the most popular devotional images.[v] As is standard of the tradition, Christ’s arms are raised to show the stigmata, his bleeding side wound is exposed, and his face drips with blood from his piercing crown of thorns. The tiered angels flanking Christ enthroned on a rainbow and the inclusion of the trumpet also mirror depictions of the Last Judgement. The depictions of this scene in the other witnesses are precisely referential to the text. The scene in Kk.1.7 is not entirely responsive to the text, and its iconography refers to extratextual traditions. Christ in this scene attains greater visual potency than Michael.

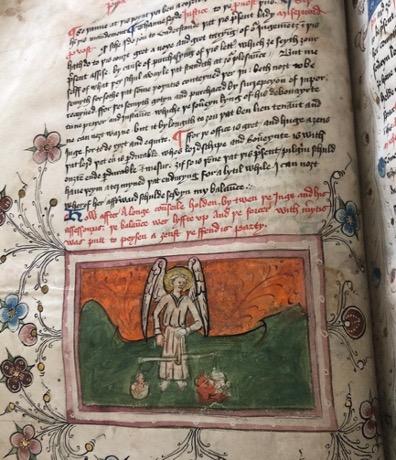

In another scene, however, on fol. 32v, the soul’s merits are weighed against his sins, and Michael is depicted instead of Justice, who is rendered prominently in most of the other witnesses. The iconography of Michael holding the scales was prevalent in medieval English wall paintings and reflects this illustrator’s tendency to conform to pictorial iconographic formulae.[vi]

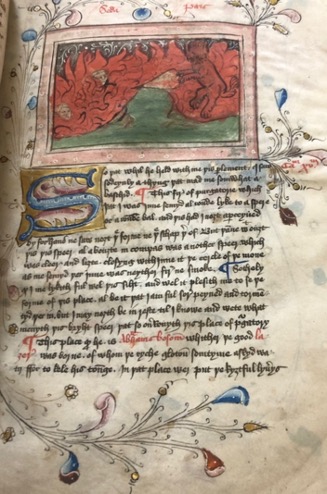

As the pictorial cycle progresses, scenes of torture abound. One such scene (fol. 46r) purports to show ‘þe schap of þe fire of purgatory’. The other manuscripts that illustrate this scene are consistent. They present the soul on his back ensconced in flames within concentric circles.[vii] The equivalent miniature in Kk.1.7 diverges from this treatment, as it shows a devil blowing the flames of Purgatory at two souls. This iconography is more generalised, for the torment of sinners in Hell was a well-worn theme with a varied iconography in the visual arts.

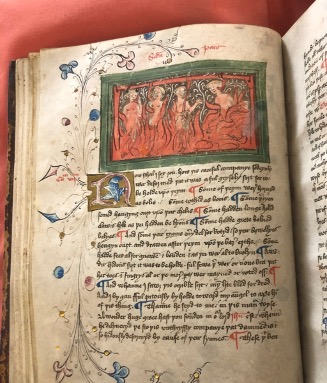

In the Hell visions of Saint Paul and of Saint Patrick, sinners are shown suspended by different body parts above fire.[viii] The illustrator of Kk.1.7 adopted this iconography twice, as four souls on fol. 37v and three souls on fol. 56r hang from hooks by various limbs above a blazing fire.

The subjects of the programme of the Soul manuscripts that have been omitted in Kk.1.7 did not typically appear in medieval visual arts, and so they do not carry the same visual associations as the previously mentioned subjects in Kk.1.7. There was no established iconography associated with the figure of Lady Liberality, for instance, and the scene in which the soul hears the story of Lady Liberality is not included in Kk.1.7. Other scenes are omitted in favour of ones with greater visual resonance. The scenes in which Justice testifies against the soul, Mercy pleads in the soul’s defense, and Christ’s grace outweighs the soul’s sins are not included in Kk.1.7, though they appear in many of the other witnesses. The scene in which the soul sees people he knew on earth does not have a set iconography in pictorial representation and is again omitted in Kk.1.7.

The fact that illustrations were conceived as a part of the manuscript tradition of the Soul and that the miniatures in Kk.1.7 are associated with visual iconographies would suggest that there was a desire to emphasise the visual and encourage the visualisation of the ‘pilgrimage of the soul’. Connections to extratextual traditions would have been readily made by means of the miniatures in Kk.1.7. The miniatures may have then functioned as complementary extensions of the text, as aids to meditative activity. The function of miniatures in late medieval English vernacular literary manuscripts cannot be generalised, but close analysis of those in the individual witnesses of a text is essential. Slight variations in the choice and treatment of the miniatures should be considered, for even minor differences would have offered a different experience for the reader.

Dana Malefakis; Research conducted as part of the M.Phil in English: medieval and Renaissance Literature, Faculty of English, University of Cambridge

[i] For a chart of the subjects chosen for illustration in each of the Soul manuscripts, see Rosemarie Potz McGerr, The Pilgrimage of the Soul: A Critical Edition of the Middle English Dream Vision, 2 vols (New York: Garland, 1990), I, pp. xlvii-xlix.

[ii] Connections between Le Pèlerinage de la Vie Humaine and medieval drama have been discussed by Edgar T. Schell, ‘On the Imitation of Life’s Pilgrimage in “The Castle of Perseverance”’, The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 67 (1968), 235-248.

[iii]See David W. Atkinson, ‘The English ars morendi: Its Protestant Transformation’, Renaissance and Reformation, 6 (1982), 1.

[iv] See Schell, 241.

[v] See Catherine R. Puglisi and William L. Barcham, eds., New Perspectives on the Man of Sorrows (Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 2013).

[vi] See Richard F. Johnson, Saint Michael the Archangel in Medieval English Legend (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2005), p. 148.

[vii] Descriptions of the depictions of this scene in the other manuscript copies of the Soul are reported in Lesley Suzanne Lawton, ‘Text and Image in Late Medieval English Vernacular Literary Manuscripts’ (unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of York, 1982), p. 125.

[viii]See Jan N. Bremmer, ‘Christian Hell: From the Apocalypse of Peter to the Apocalypse of Paul’, Numen, 56 (2009), 308.