Bob Dylan working in a room above the Cafe Espresso in Woodstock, N.Y., in 1964.

at Cambridge

Bob Dylan working in a room above the Cafe Espresso in Woodstock, N.Y., in 1964.

I didn’t realise something was missing. Or rather, I didn’t realise that I would care that something was missing. In fact, I was pretty sure that a November which didn’t involve dodging my mother’s annual pie bake-a-thon, explaining to my Dad for fiftieth time why my husband and I wouldn’t be eating the turkey (we eat kosher), shuttling my son to my ex-husband’s parents’ house halfway though the day, and then helping clean up after a dinner party of 25, sounded just about perfect.

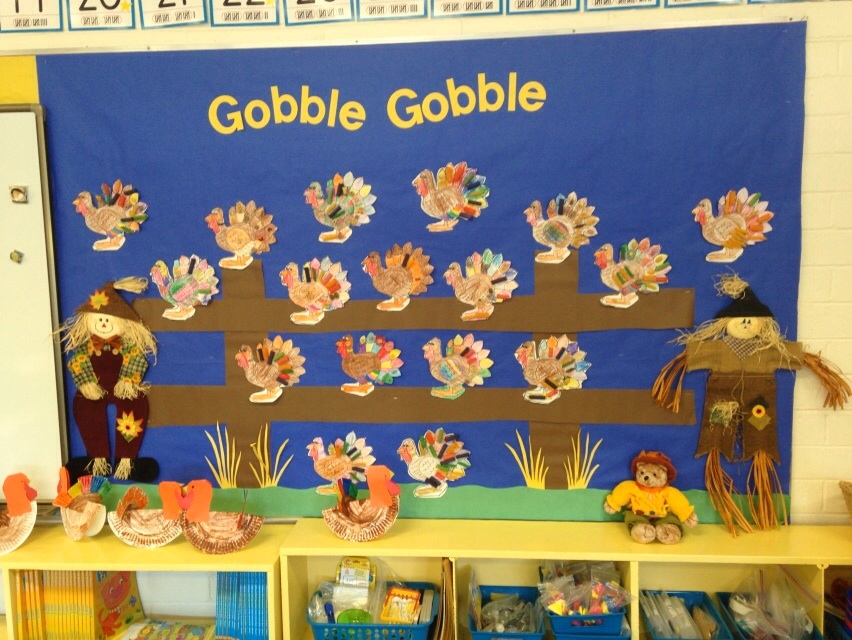

But on Monday morning, I woke up to this…

…a photo of a festively decorated bulletin board from my mother’s Kindergarten classroom. In case you are not well versed in the finer American arts, the rainbow-tailed, avian effigies pictured above are colour-cut-and-glue turkeys. Sometimes these garish gobblers come in the form of hand tracings, coloured to resemble turkeys, other times they are assembled from pre-made outlines that have been photocopied from the same Xerox master copy for decades; passed down from one teacher to another upon retirement…along with a box of paper-plate Puritan hats, and politically incorrect Native American pasta necklaces. In fear of causing a cultural-insensitivity uproar, the contents of said inherited box would be immediately discarded… all except for the Xerox turkey master copy… it’s worth its weight in gold(en) mashed potatoes.

…a photo of a festively decorated bulletin board from my mother’s Kindergarten classroom. In case you are not well versed in the finer American arts, the rainbow-tailed, avian effigies pictured above are colour-cut-and-glue turkeys. Sometimes these garish gobblers come in the form of hand tracings, coloured to resemble turkeys, other times they are assembled from pre-made outlines that have been photocopied from the same Xerox master copy for decades; passed down from one teacher to another upon retirement…along with a box of paper-plate Puritan hats, and politically incorrect Native American pasta necklaces. In fear of causing a cultural-insensitivity uproar, the contents of said inherited box would be immediately discarded… all except for the Xerox turkey master copy… it’s worth its weight in gold(en) mashed potatoes.

But I digress.

Monday morning found me in want of turkeys. It found me in want of overly simplistic renderings of the pilgrim/Native American food swap and celebration. It found me in want of handmade cornucopias made from badly coloured paper plates stapled together with poorly cutout pictures of fruit. It found me in want of the familiar — not that Cambridge is entirely unfamiliar to the American eye — but the knowledge that the familiar was taking place without me…found me wanting.

Luckily there are two other expat families in our complex who were experiencing similar “wantings,” so today we will be hosting our own food swap, complete with semi-crazed “bake-a-thon,” confused explanations of why our family is not eating turkey, and cleaning up after a massively large dinner party… as well as a communal watching of Charlie Brown’s Thanksgiving and perhaps Disney’s The Adventure of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (narrated by the king of American holidays – Bing Crosby) while the tryptophan sets in.

Happy T-day everyone.

Recommended T-day Movie Watch List (via youtube!)

Charlie Brown’s Thanksgiving (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQ961y0VKEk)

Really gets at the heart of the American cultural matter.

Disney’s The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2cjfDGJHGko) – I have no idea why these are paired together, but it’s part of the experience. Please note – Ichabod is Ichabod Crane from Washington Irving’sThe Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

Ben Lerner’s recent second novel, 10:04, carries the following epigraph:

The Hassidim tell a story about the world to come that says everything there will be just as it is here. Just as our room is now so it will be in the world to come; where our baby sleeps now, there too it will sleep in the other world. And the clothes we wear in this world, those too we will wear there. Everything will be as it is now, just a little different.

Like any good Hassidic story, this one has a convoluted genealogy. In his acknowledgements at the back of the book, Lerner says that he came across it in Giorgio Agamben’s The Coming Community, although it is, he writes, ‘typically attributed to Walter Benjamin’. What Lerner doesn’t say is that Benjamin said that he heard the story from Gershom Scholem, and that, before writing it down himself, he had recounted it to Ernst Bloch, who transcribed a variation of it (‘just a little different’) in Spuren:

A rabbi, a real cabbalist, once said that in order to establish the reign of peace it is not necessary to destroy everything or to begin a completely new world. It is sufficient to displace this cup or this bush or this stone just a little, and thus everything. But this small displacement is so difficult to achieve and its measure is so difficult to find that, with regard to the world, humans are incapable of it and its necessary that the Messiah come.

This version also appears alongside Benjamin’s in The Coming Community. In citing Agamben, Lerner leads us back to this second story, such that it becomes a kind of shadow– or alter– epigraph to 10:04, working in relief to the printed version of the tale.

10:04 is the story of Ben, the novel’s writer-protagonist. Ben’s first book has been a surprise hit (like Lerner’s) and he’s now faced with what might be called the second-album question: how to replicate his initial success, while producing something new? On top of this, he is suffering from an unknown disease, and his best friend, Alex, is pressuring him into starting IVF treatment so that she can have a baby. The printed version of the Hassidic story would thus seem to comment upon some of the novel’s thematic concerns: the closeness of artistic creation to replication, the idea of artificiality and its connection to re-production, both artistic and biological.

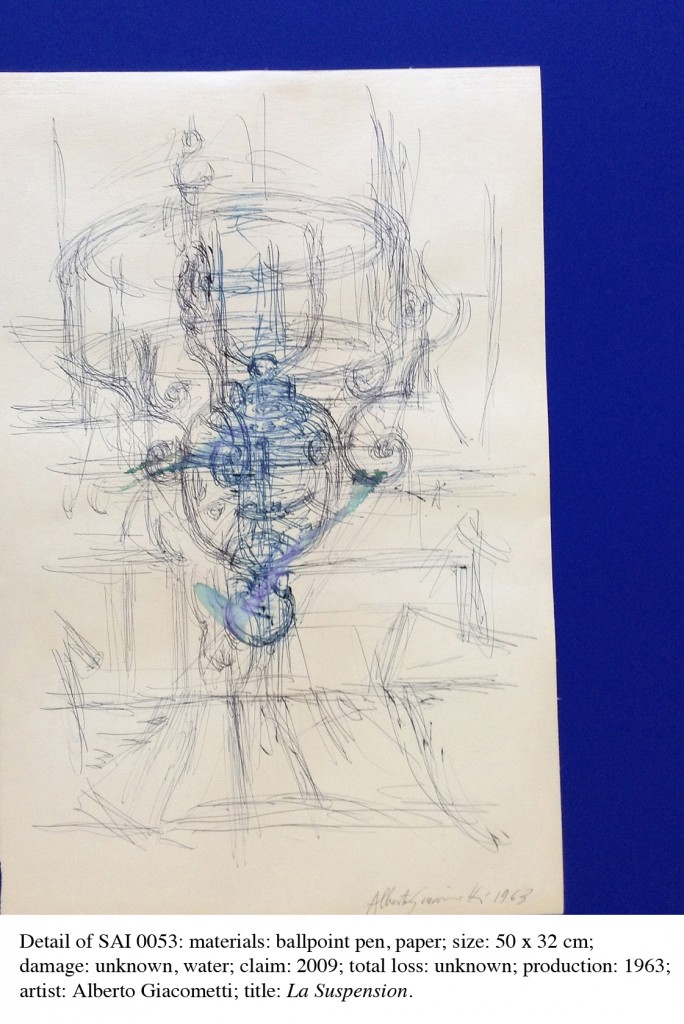

But the puzzle doesn’t quite end there. Lerner has, it turns out, quoted the story before: you can find Benjamin’s version in his Harper’s essay “Damage Control”, a meditation on the contradictions of art-market economics. The piece meanders through a history of art vandalism, before dwelling on the “Salvage Art Institute”, a project in which curator Elka Krajewska exhibited damaged (or ‘total loss’) pieces of work by famous artists deemed financially ‘worthless’ by the company that insured them, despite that fact that many, Lerner writes, ‘seemed perfectly in tact’.

Parts of Lerner’s Harper’s essay also find their way into 10:04: some of them a bit broken up, but others reproduced verbatim, ‘perfectly in tact’ (it is Alex who starts the “Institute for Totaled Art” in the novel, leading Ben to repeat Lerner’s own exegesis). And it is not the only example of Lerner lifting from his own material and working it into the book: the entire second chapter is in fact a reproduction of one of his New Yorker stories (complete with pseudo-Irvin title typeface); another section first appeared in the Paris Review, while Lerner has already separately published some of the poems Ben writes while at a writer’s retreat.

With this in mind, the Hassidim’s tandem tales take on a new resonance. Their double story of repetition and displacement becomes not only a way into the novel’s themes, but to Lerner’s aesthetic process throughout the book: they unmask what we might call his ‘curatorial practice’ of re-using, re-contextualising, and re-imagining parts of his existing work as creative work in and of itself.

Stacy Schiff reviews Letters to Véra by Vladimir Nabokov, edited and translated from the Russian by Olga Voronina and Brian Boyd, and Nabokov in America: On the Road to Lolita

by Robert Roper in this week’s New York Review of Books.

‘Walden is less a cornerstone work of environmental literature than the original cabin porn: a fantasy about rustic life divorced from the reality of living in the woods, and, especially, a fantasy about escaping the entanglements and responsibilities of living among other people.’

On the terrace at the Whitney, September 2015

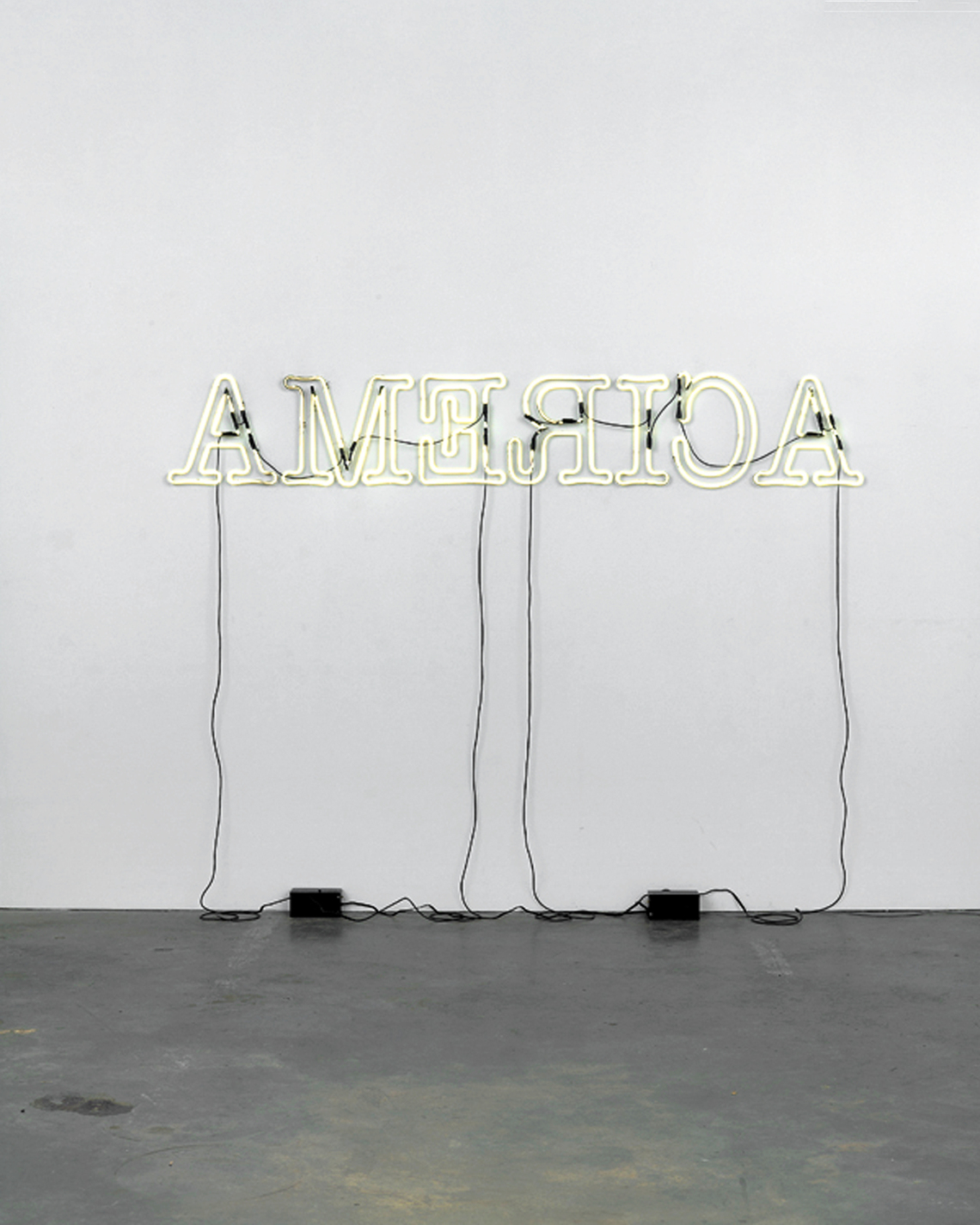

On a recent trip to New York, I visited the new Whitney Museum of American Art. The museum recently moved from Manhattan’s Upper East Side to large new premises in the Meatpacking District overlooking the Hudson River. It opened in May with a suitably ambitious exhibition entitled ‘America is Hard to See’ (a phrase borrowed from a 1951 meditation on Columbus by Robert Frost). As one of the curators explained, the exhibition does not claim to offer a ‘comprehensive history’ of American art so much as ‘a series of provocative thematic chapters’. The concluding chapter, ‘Course of Empire’, takes its title from a series of works by Ed Ruscha (from 2005), which in turn alludes to Thomas Cole’s 1833-36 series, The Course of Empire, the title of which comes from the opening line of a 1729 poem by Bishop George Berkeley.

Allusion accrues and intensifies in the exhibition’s final chapter; not least in Glenn Ligon’s Rückenfigur (2009). The work is steeped in art history –from signage and minimalist neon sculpture to the ancient convention of the figure seen from behind whose perspective the viewer is invited to share. A famous example is Caspar David Friedrich‘s Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer (1818); wanderer above the sea of fog.

Caspar David Friedrich,

Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer (1818)

oil on canvas (98.4 cm × 74.8 cm)

Kunsthall Hamburg

Glenn Ligon, Rückenfigur, 2009.

Neon and paint (61 × 369.6 × 12.7 cm).

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© Glenn Ligon; Courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, LA

‘And that’s one of the really interesting things about this piece,’ says the curator Scott Rothkopf, ‘this idea of America, this country, this word facing away from us but at the same time addressing us. …You see the fragile connections between these letters, which I think suggests the sense of America, this country, as a confederacy that’s both united and sometimes divided. And I think that all of those things, in a way, function metaphorically for where this country is at this moment.’

Rückenfigur is part of an (ongoing?) series of neons that riff on national symbolism. The first, from 2006 – now on show at the Tate – had the neon painted black and intermittently turn off. Ligon described it as a response to the idea ‘that America, for all its dark deeds, is still this shining light. That’s how the piece came about, because I was thinking about Dickens’s “the best of times, the worst of times.” Yes, that’s where America is. We can elect Barack Obama, and we’re still torturing people in prisons in Cuba.’

As the series progresses, the shining light is getting harder to see. The most recent addition, exhibited in Los Angeles earlier this year, features two neon Americas face down on the floor There’s no more foggy ambiguity here; no more pleasure in the wandering processes of our own perception. Instead, I am reminded of the final painting in Cole’s series – Desolation.

Installation view of Glenn Ligon,

Well, it’s bye-bye/If you call that gone

Regen Projects, Los Angeles

March 14 – April 18, 2015

Thomas Cole, Desolation. 1836 (99.7 x 160.7 cm) New York Historical Society

© 2025 American Literature

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments