Ben Lerner’s recent second novel, 10:04, carries the following epigraph:

The Hassidim tell a story about the world to come that says everything there will be just as it is here. Just as our room is now so it will be in the world to come; where our baby sleeps now, there too it will sleep in the other world. And the clothes we wear in this world, those too we will wear there. Everything will be as it is now, just a little different.

Like any good Hassidic story, this one has a convoluted genealogy. In his acknowledgements at the back of the book, Lerner says that he came across it in Giorgio Agamben’s The Coming Community, although it is, he writes, ‘typically attributed to Walter Benjamin’. What Lerner doesn’t say is that Benjamin said that he heard the story from Gershom Scholem, and that, before writing it down himself, he had recounted it to Ernst Bloch, who transcribed a variation of it (‘just a little different’) in Spuren:

A rabbi, a real cabbalist, once said that in order to establish the reign of peace it is not necessary to destroy everything or to begin a completely new world. It is sufficient to displace this cup or this bush or this stone just a little, and thus everything. But this small displacement is so difficult to achieve and its measure is so difficult to find that, with regard to the world, humans are incapable of it and its necessary that the Messiah come.

This version also appears alongside Benjamin’s in The Coming Community. In citing Agamben, Lerner leads us back to this second story, such that it becomes a kind of shadow– or alter– epigraph to 10:04, working in relief to the printed version of the tale.

10:04 is the story of Ben, the novel’s writer-protagonist. Ben’s first book has been a surprise hit (like Lerner’s) and he’s now faced with what might be called the second-album question: how to replicate his initial success, while producing something new? On top of this, he is suffering from an unknown disease, and his best friend, Alex, is pressuring him into starting IVF treatment so that she can have a baby. The printed version of the Hassidic story would thus seem to comment upon some of the novel’s thematic concerns: the closeness of artistic creation to replication, the idea of artificiality and its connection to re-production, both artistic and biological.

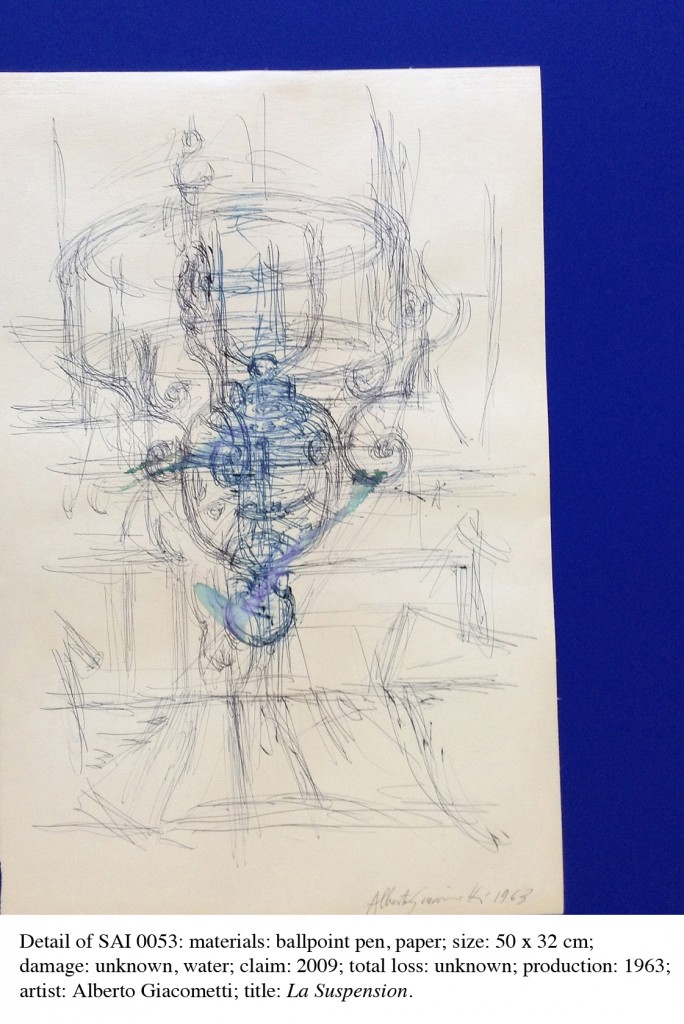

But the puzzle doesn’t quite end there. Lerner has, it turns out, quoted the story before: you can find Benjamin’s version in his Harper’s essay “Damage Control”, a meditation on the contradictions of art-market economics. The piece meanders through a history of art vandalism, before dwelling on the “Salvage Art Institute”, a project in which curator Elka Krajewska exhibited damaged (or ‘total loss’) pieces of work by famous artists deemed financially ‘worthless’ by the company that insured them, despite that fact that many, Lerner writes, ‘seemed perfectly in tact’.

Parts of Lerner’s Harper’s essay also find their way into 10:04: some of them a bit broken up, but others reproduced verbatim, ‘perfectly in tact’ (it is Alex who starts the “Institute for Totaled Art” in the novel, leading Ben to repeat Lerner’s own exegesis). And it is not the only example of Lerner lifting from his own material and working it into the book: the entire second chapter is in fact a reproduction of one of his New Yorker stories (complete with pseudo-Irvin title typeface); another section first appeared in the Paris Review, while Lerner has already separately published some of the poems Ben writes while at a writer’s retreat.

With this in mind, the Hassidim’s tandem tales take on a new resonance. Their double story of repetition and displacement becomes not only a way into the novel’s themes, but to Lerner’s aesthetic process throughout the book: they unmask what we might call his ‘curatorial practice’ of re-using, re-contextualising, and re-imagining parts of his existing work as creative work in and of itself.

This is a great piece, Mike, and very convincing. Can you say a bit more about all this in relation to the novel’s interest in money, in writing for a living, what writing/art is ‘worth’?

Yes, excellent piece! More on writing as curation, please. Seems to be the concept of the moment.

Thank you for the comments! Money’s really interesting in the book (and will no doubt continue to be a theme in Lerner’s work after winning the MacArthur): it is both a spur for writing and the block – rather like in ‘Zuckerman Unbound’, Philip Roth’s book about life after the million-dollar success of ‘Portnoy’s Complaint’ (the opening line: ”What the hell are you doing on a bus, with your dough?”). And as you suggest, money is part of the novel’s concern with ‘value’, with worth. There are some great moments when Ben’s associative thinking collapses the distance between different kinds of value: looking at some of the totalled works of art, he notes that they were originally worth “somewhere between five thousand and ten thousand dollars, between one and two IUIs [Intrauterine inseminations], a year or two of Chines labor”. And the larger question being circled: does this practice of curation amount to, or add up to, a novel? Is it worth the same?