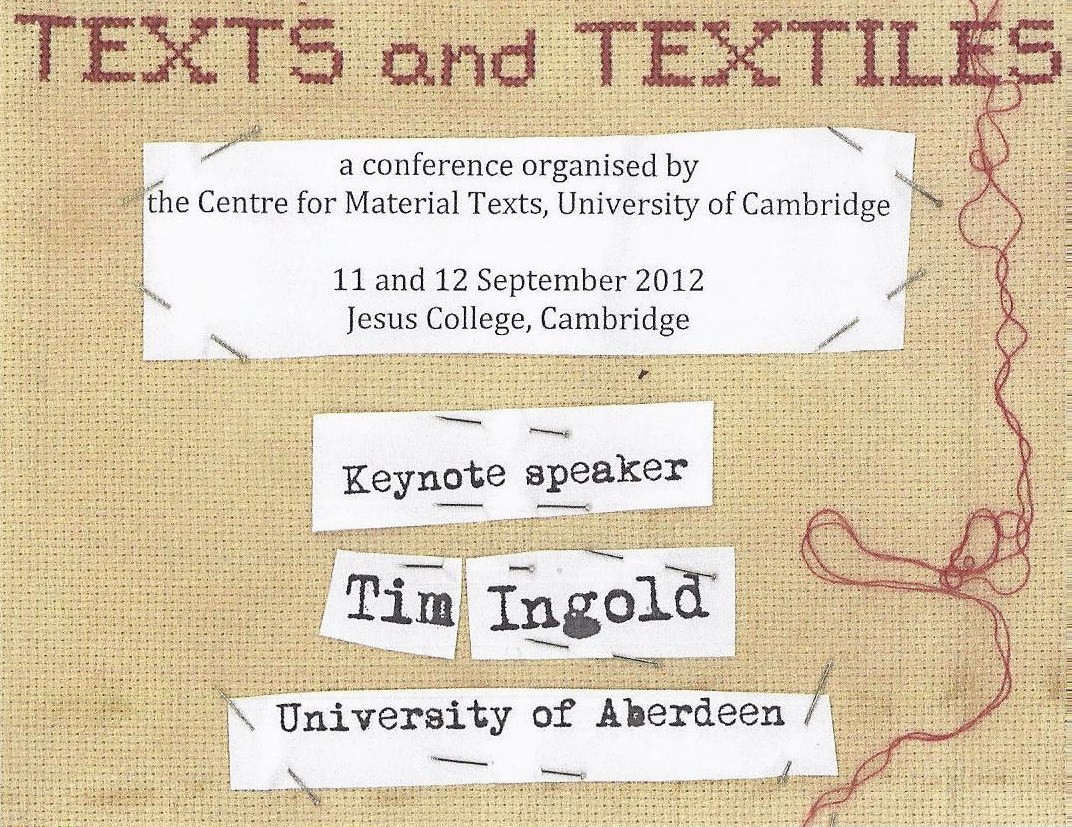

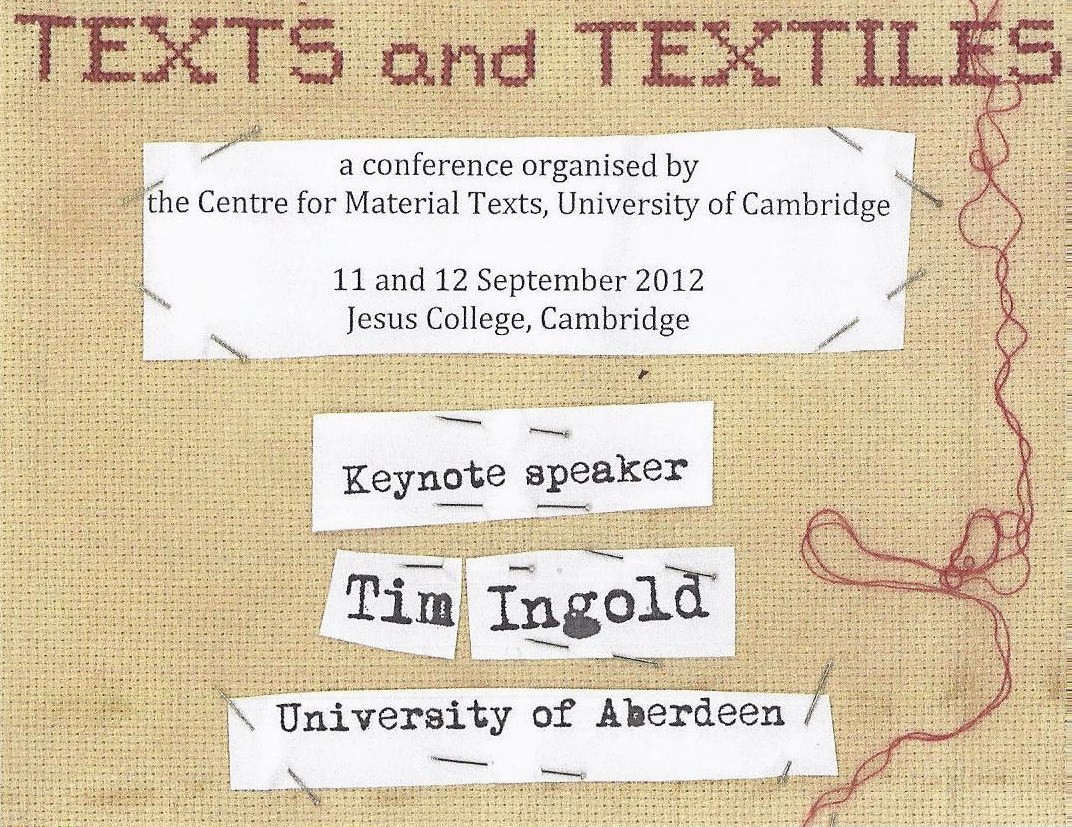

How do the fabrics of language intersect with the languages of fabric? This was the question at the heart of the CMT’s ‘Texts and Textiles’ conference, which took place over two days (11-12 September 2012) at Jesus College. Co-organized by Lucy Razzall and Jason Scott-Warren, and generously supported by a grant from the Faculty of English, the conference responded to the Centre’s current research theme on ‘The Material Text in Material Culture’. Speakers and delegates from across the world converged on Cambridge for the conference, literary critics, historians and anthropologists mingling with textile designers, artists, and librarians. Our fifteen panels and forty-four speakers approached the conference’s theme from many and varied angles.

How do the fabrics of language intersect with the languages of fabric? This was the question at the heart of the CMT’s ‘Texts and Textiles’ conference, which took place over two days (11-12 September 2012) at Jesus College. Co-organized by Lucy Razzall and Jason Scott-Warren, and generously supported by a grant from the Faculty of English, the conference responded to the Centre’s current research theme on ‘The Material Text in Material Culture’. Speakers and delegates from across the world converged on Cambridge for the conference, literary critics, historians and anthropologists mingling with textile designers, artists, and librarians. Our fifteen panels and forty-four speakers approached the conference’s theme from many and varied angles.

Literary Perspectives

The text/textile interface has often surfaced as an explicit preoccupation in literature. Giovanni Fanfani and Ellen Harlizius-Klück (Centre for Textile Research in Copenhagen) explored the structural similarities between ancient Greek textual analysis and techniques of weaving, with particular attention to the relationship between the ‘starting border’ of a cloth and the prooimion of a text such as Hesiod’s Theogony. Andrew Zurcher (Cambridge) followed the migration of the shirt of Nessus from Sophocles and Ovid, via Seneca, to Shakespeare. As it travels, this poison-soaked garment raises important questions about agency and criminal culpability and perhaps hints at a tragic association between threads and fate. Megan Cavell (Toronto) took us to Anglo-Saxon England, where poets ostentatiously bound, locked and interlaced their  words, giving them the solidity of textiles or metalwork—via forms of ‘cræft’ that could also carry troubling connotations of deception and treachery.

words, giving them the solidity of textiles or metalwork—via forms of ‘cræft’ that could also carry troubling connotations of deception and treachery.

Several papers addressed the role of textiles in seventeenth-century English texts. Alison Knight (Cambridge) examined the poems of George Herbert as a response to the Protestant notion that the Scriptures present a tight verbal weave that cannot be broken or torn without loss. As they wield their chapter and verse, Herbert’s lyric speakers are themselves cut adrift, and can only find peace through a recovery of Biblical ‘contexture’. Christopher Burlinson (Cambridge) pursued the web of textile metaphors, and in particular of references to gossamer, in Robert Herrick’s Hesperides. In the seventeenth century there was no certainty about what gossamer was, and its elusive insubstantiality hints at the mysterious connections of Herrick’s poetics. Deborah Rosario (Oxford) studied Eve’s floral bower in Milton’s Paradise Lost, inviting us to think about the relationship between natural and manmade artifice in this highly ‘wrought’ environment.

Moving further forward in time, and crossing the Atlantic, Katie McGettigan (Keele) looked at the playful exchanges between rags and paper in Melville’s Pierre, contextualizing them in relation to a broader cultural fascination with the unseen transformations that take place in paper-making, while Rebecca Varley-Winter (Cambridge) pondered the relationship between collage-poems by Mina Loy and Marianne Moore and the surrealist assemblages of Max Ernst. Bringing the literary tour bang-up-to-date, Maria Damon (Minnesota) exposed some of the paradoxes that bedevil the ‘slow-poetry’ movement and the recent renaissance of craft-based making. Ought we to applaud these attempts to make critical space amid the frenzy of modernity, or should we be put off by their ‘suspicious nostalgia’?

The Stuff of Books

Many contributions to the conference pursued the textile into the material fabric of books and documents. Allison Jai O’Dell (Corcoran College) spoke (via Skype) about the importance of establishing a precise classification and terminology for sewing structures within the bibliographical study of bookbinding. Georgios Boudalis (Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki) reviewed a number of sewing structures found in the history of bookbinding, suggesting parallels between ancient methods used in the making of books and socks. (This prompted some debate here about the relative cultural significance of books and socks!) Clemence Schultze (Durham) explored the evidence for the writing of ritual texts on linen in ancient Rome, while Katya Oichermann (Goldsmiths) unfurled the stories and histories that circulated in the cloths that swaddled German Jewish boys during their circumcision ceremonies, which were later transformed into highly decorative ‘Torah binders’, for wrapping the sacred scrolls when not in use. Ralph Isaacs OBE (Director of the British Council in Burma from 1989 to 1994) displayed and discussed some exquisite Burmese manuscript binding tapes, decoding their rich symbolism and the record they offer of their own making. Joy Boutrup (Kolding School of Design) and Janice Sibthorpe (Royal College of Art) both discussed the art of the seventeenth-century English loop braid, which could be used as love token, purse-string, or bookmark, as long as it came festooned with symbols and texts. Georgianna Ziegler (Folger Shakespeare Library) discussed some wonderful images of early modern books (including a particularly beautiful binding in cut-work vellum), demonstrating the close connections between

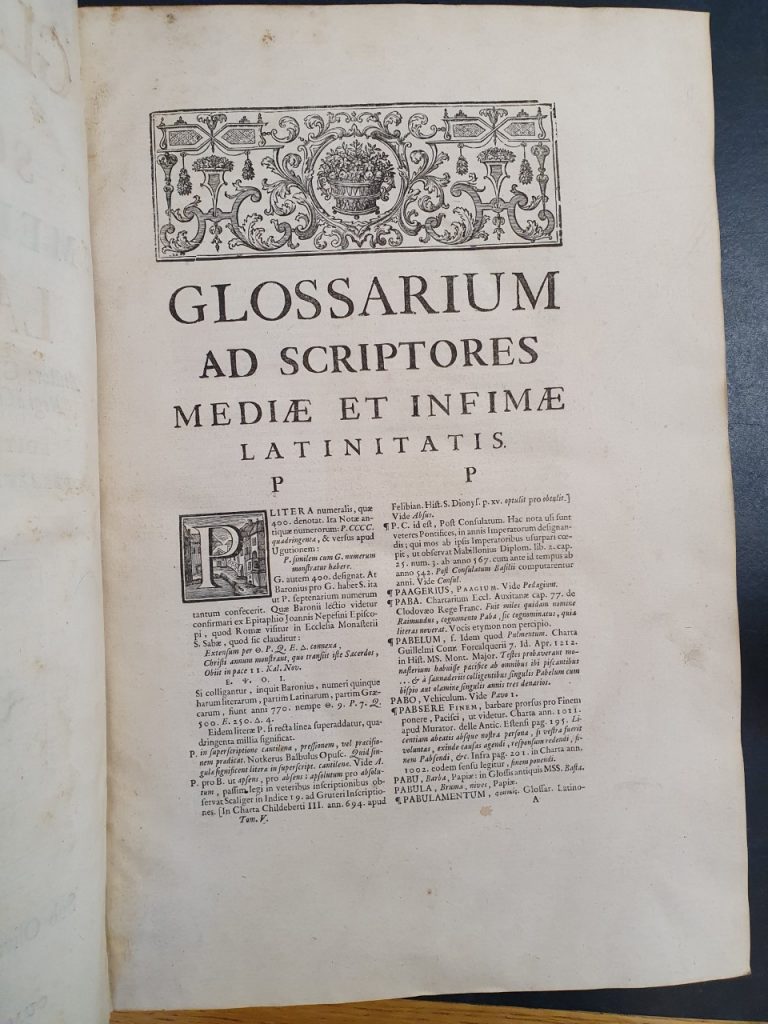

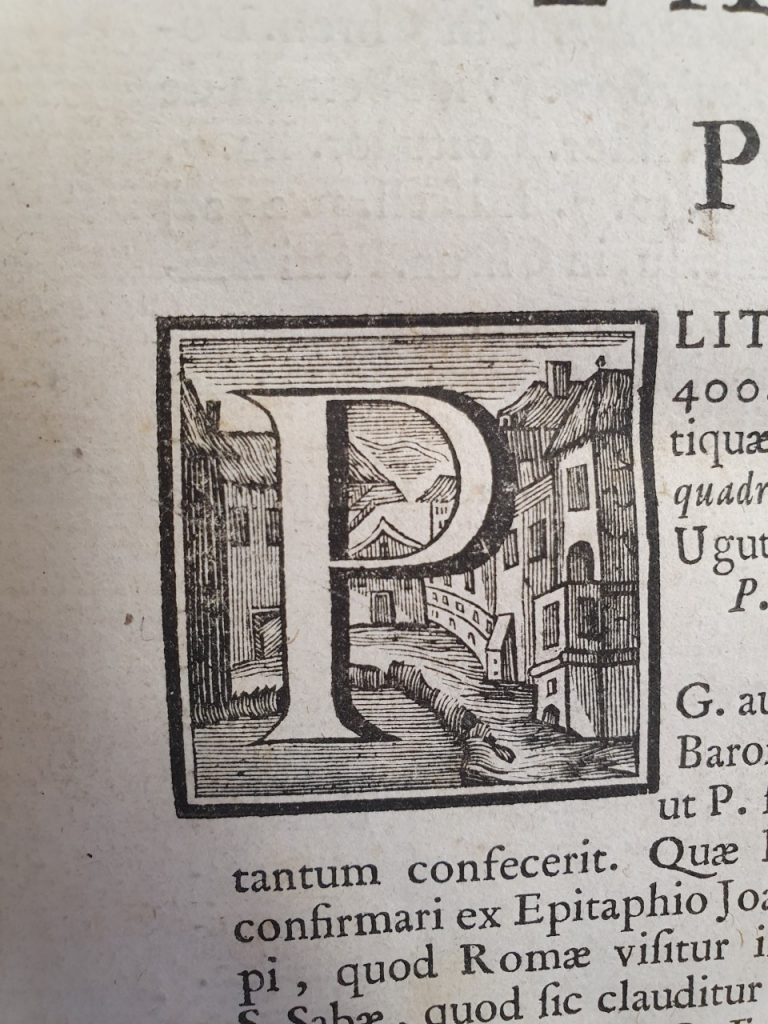

Many contributions to the conference pursued the textile into the material fabric of books and documents. Allison Jai O’Dell (Corcoran College) spoke (via Skype) about the importance of establishing a precise classification and terminology for sewing structures within the bibliographical study of bookbinding. Georgios Boudalis (Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki) reviewed a number of sewing structures found in the history of bookbinding, suggesting parallels between ancient methods used in the making of books and socks. (This prompted some debate here about the relative cultural significance of books and socks!) Clemence Schultze (Durham) explored the evidence for the writing of ritual texts on linen in ancient Rome, while Katya Oichermann (Goldsmiths) unfurled the stories and histories that circulated in the cloths that swaddled German Jewish boys during their circumcision ceremonies, which were later transformed into highly decorative ‘Torah binders’, for wrapping the sacred scrolls when not in use. Ralph Isaacs OBE (Director of the British Council in Burma from 1989 to 1994) displayed and discussed some exquisite Burmese manuscript binding tapes, decoding their rich symbolism and the record they offer of their own making. Joy Boutrup (Kolding School of Design) and Janice Sibthorpe (Royal College of Art) both discussed the art of the seventeenth-century English loop braid, which could be used as love token, purse-string, or bookmark, as long as it came festooned with symbols and texts. Georgianna Ziegler (Folger Shakespeare Library) discussed some wonderful images of early modern books (including a particularly beautiful binding in cut-work vellum), demonstrating the close connections between calligraphy and lace-making in both aesthetic and authorial terms (‘printer’s lace’ will never look the same again). And, staying in the early modern period, Claire Canavan (York) taught us how to judge a book by its cover, exploring a seventeenth-century stumpwork binding bearing an image of Sarah and Hagar. Such a binding didn’t just hold a book together; it also bound it outward to its environment and helped to make it ‘articulate in use’.

calligraphy and lace-making in both aesthetic and authorial terms (‘printer’s lace’ will never look the same again). And, staying in the early modern period, Claire Canavan (York) taught us how to judge a book by its cover, exploring a seventeenth-century stumpwork binding bearing an image of Sarah and Hagar. Such a binding didn’t just hold a book together; it also bound it outward to its environment and helped to make it ‘articulate in use’.

Seeing and Touching

Other speakers turned our attention to the visual arts, with which textile work has always had an intimate relationship, despite the fact that it has often had to play second fiddle. Beth Williamson (Tate) offered a history of textile education at Goldsmith’s College, dwelling on the increasing integration of Textiles into Fine Art, and the slow erasure of any clear demarcation between the two fields. Georgina Gajewski (North Carolina at Chapel Hill) focused on a single embroidered landscape executed by a student at the Raleigh Academy in North Carolina in 1826. Her paper offered a nuanced account of the intertwining of ideals of femininity with political aspirations and aesthetic codes in the period.

Linda Newington (Winchester) shared some of the riches of the knitting reference library at the Winchester School of Art (an absolute treasure-trove for social historians as well as knitters, containing patterns and knitted objects) and also described the library’s evolving collection of ‘artists’ books’. Her images included many beautiful and thought-provoking examplars which raised questions about the hand-made, the relationship between object, image and text, and the ever-expanding category of ‘the book’. (One among these was a printed cloth guide to making a stuffed toy rabbit, its final instruction surely more widely applicable: ‘hang from ears and hope for spring’). Sophie Aymes-Stokes (Bourgogne) presented a detailed account of changing practices in book illustration in relation to evolving attitudes towards the ‘photographic’ and the ‘mechanically reproduced’.

Linda Newington (Winchester) shared some of the riches of the knitting reference library at the Winchester School of Art (an absolute treasure-trove for social historians as well as knitters, containing patterns and knitted objects) and also described the library’s evolving collection of ‘artists’ books’. Her images included many beautiful and thought-provoking examplars which raised questions about the hand-made, the relationship between object, image and text, and the ever-expanding category of ‘the book’. (One among these was a printed cloth guide to making a stuffed toy rabbit, its final instruction surely more widely applicable: ‘hang from ears and hope for spring’). Sophie Aymes-Stokes (Bourgogne) presented a detailed account of changing practices in book illustration in relation to evolving attitudes towards the ‘photographic’ and the ‘mechanically reproduced’.

The creative practice of the Bauhaus emigrée artist Anni Albers, whose encounter with pre-Columbian Andean textiles inspired her to create a new visual language, was the subject of a paper by Marianna Franzosi (an independent scholar). Angela Carr (Montréal) tracked the archival remains of the Chicana writer and critic Gloria Anzaldúa, whose papers went to Austin, Texas, while her material things (including altar cloths and tapestries) were left to the University of Santa Cruz; Carr reconsidered the latter with reference to the Aztec concept of nepentla or in-between space.

Drawing on film theory which presents the cinema screen not as a window to look through but as a surface to linger on, Athena Bellas (Melbourne) explored the Twilight Saga movies, drawing our attention to the rich sensuality of the fabrics which invite viewers to feel as much as see Bella’s bedroom as a luxurious and erotic space – a reading which challenges the frustration many commentators feel at Bella’s narrative positioning as passive and reactive. The revelation that Target, the second largest discount retailer in the United States, had brought out its own line of ‘Bella bedding’ in response to the success of the first film took us forward into questions of reception, and the ways in which a teenage audience might appropriate for themselves the fantasy space of the film.

Talking Textiles

Some textiles conjure forth extraordinary language, or extraordinary amounts of commentary, while others seem to be unspeakable, utterly resistant to verbalization. Jennifer Burek Pierce (Iowa) considered the proliferation of knitting blogs, which in her analysis work to foster an international community committed to a single craft. Kandy Diamond (Manchester) analysed the language of knitting patterns, asking how new technologies are likely to change long-established codes for the transmission of complex instructions. The value of textile thinking to large corporations was the subject broached by Anne Rippin (Bristol), who also talked about how academic prose, with its holes and seams and bodges, is like cloth.

Some textiles conjure forth extraordinary language, or extraordinary amounts of commentary, while others seem to be unspeakable, utterly resistant to verbalization. Jennifer Burek Pierce (Iowa) considered the proliferation of knitting blogs, which in her analysis work to foster an international community committed to a single craft. Kandy Diamond (Manchester) analysed the language of knitting patterns, asking how new technologies are likely to change long-established codes for the transmission of complex instructions. The value of textile thinking to large corporations was the subject broached by Anne Rippin (Bristol), who also talked about how academic prose, with its holes and seams and bodges, is like cloth.

In her paper on eighteenth-century patchwork, Bridget Long (Hertfordshire) teazed out a contradictory relationship between practice and discourse. The making of patchwork quilts and covers was integral to the well-ordered, well-run household, but in common parlance ‘patchwork’ served as a term of abuse for anything that was perceived to be second-hand or incoherent. Elsewhere, in one of the conference’s many striking juxtapositions, Kelvin Knight (East Anglia) pondered whether silk might be the unifying thread in W. G. Sebald’s travelogue The Rings of Saturn, while Victoria Mitchell (Norwich) lifted the covers on the dazzling eighteenth-century fabric pattern-books which Sebald described as ‘leaves from the only true book which none of our textual and pictorial works can even begin to rival’. That sense of competition between text and textile was not perhaps reinforced by the pattern-books, in which each swatch of calamanco comes with its own beguiling name that renders it both identifiable and desirable.

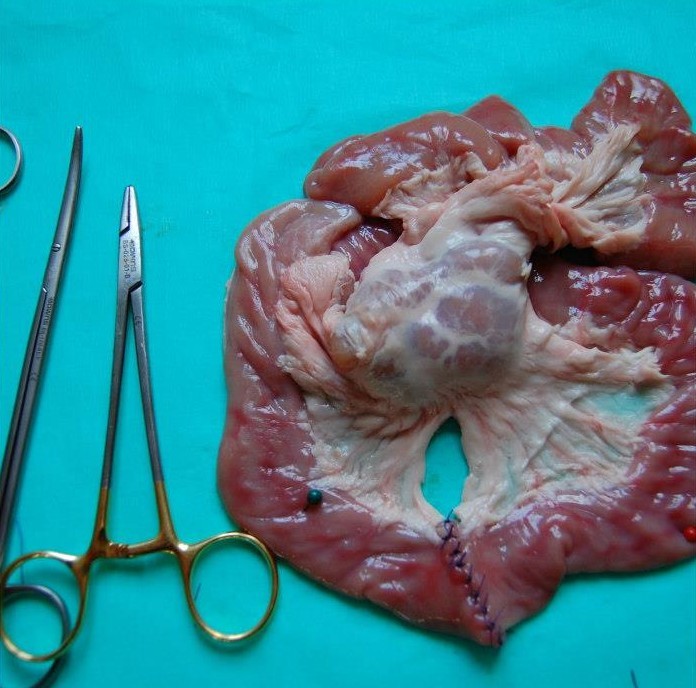

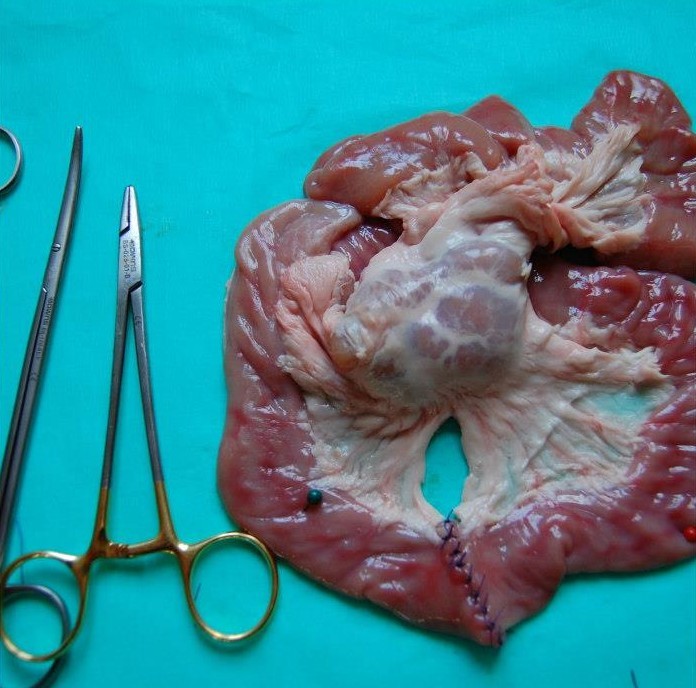

The prize for the most startling exploration of the language of textiles went to Olivia Will (West Suffolk Hospital NHS Trust), who brought a mini operating theatre, bristling with sharp implements, along to the Jesus College Upper Hall. While a surgeon with an extraordinarily steady hand showed how bodily tissue—here, the intestine of a pig—responds to the needle, Will explained the discrepancies between the textile argot used by medics in the operating theatre and what patients themselves get to hear. As the body is reduced to an object for the purposes of invasive surgery, so it is reduced to a series of fabrics, which can be stitched, tied, patched and buttonholed.

The prize for the most startling exploration of the language of textiles went to Olivia Will (West Suffolk Hospital NHS Trust), who brought a mini operating theatre, bristling with sharp implements, along to the Jesus College Upper Hall. While a surgeon with an extraordinarily steady hand showed how bodily tissue—here, the intestine of a pig—responds to the needle, Will explained the discrepancies between the textile argot used by medics in the operating theatre and what patients themselves get to hear. As the body is reduced to an object for the purposes of invasive surgery, so it is reduced to a series of fabrics, which can be stitched, tied, patched and buttonholed.

Writing with a needle

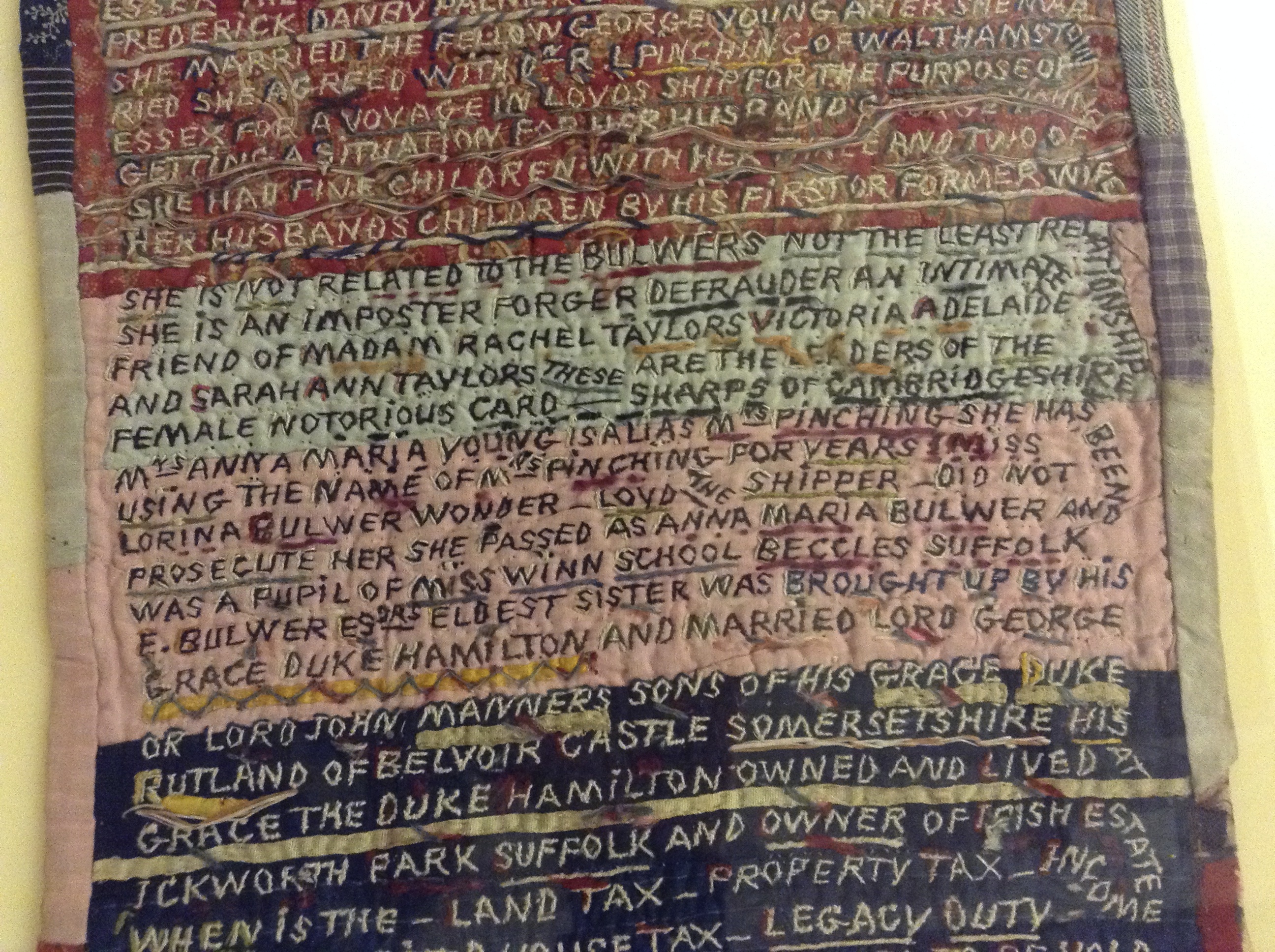

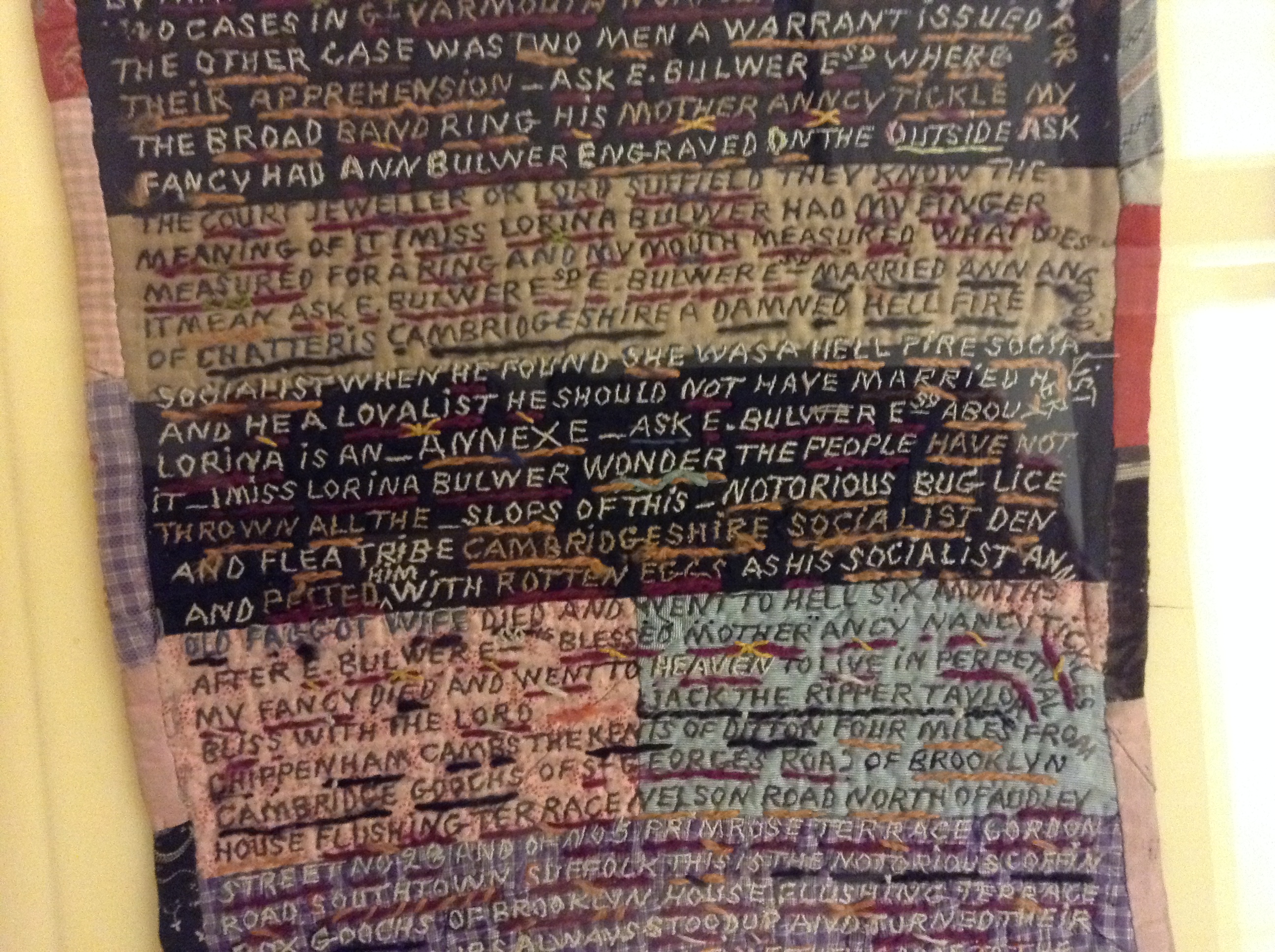

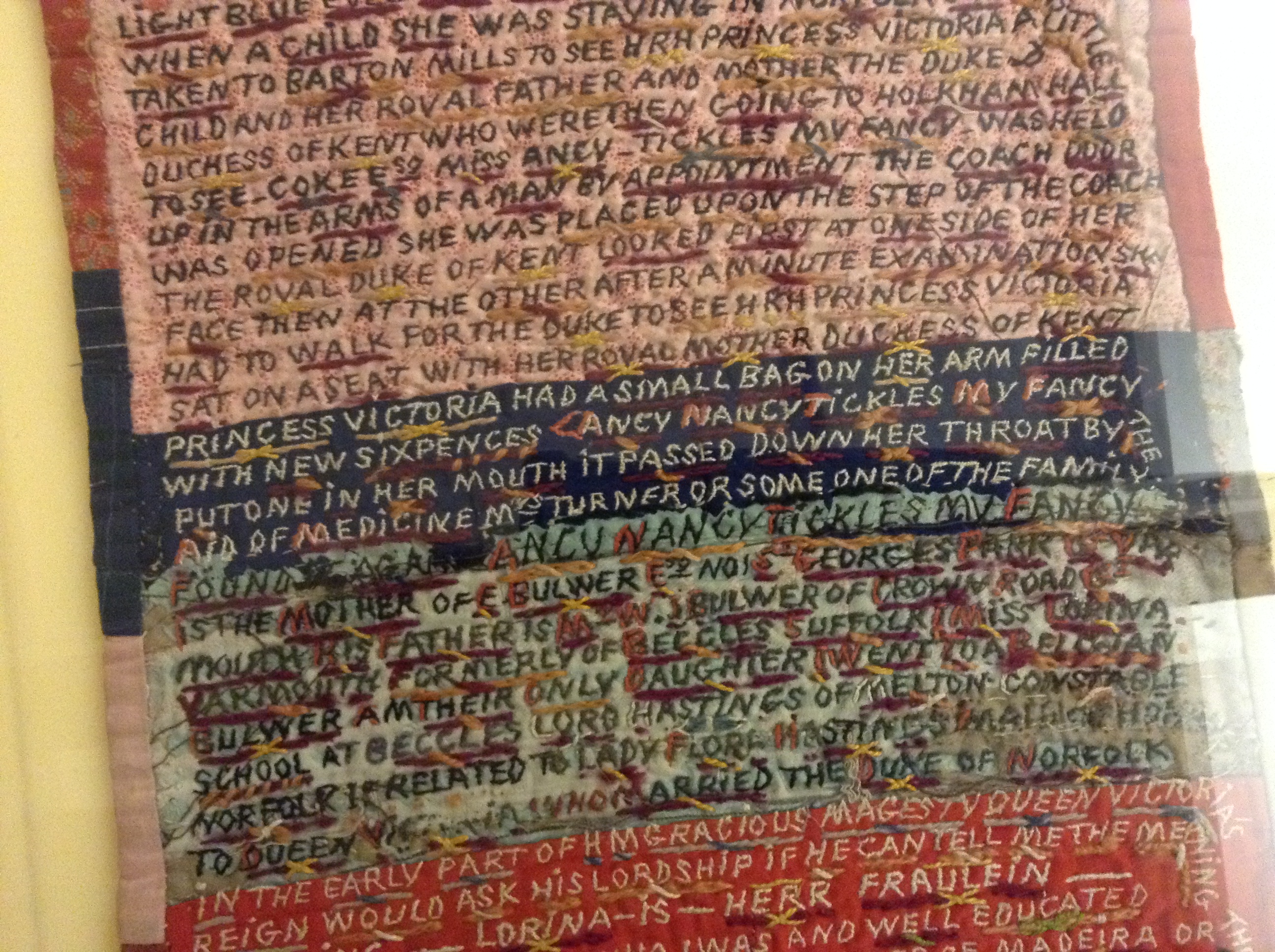

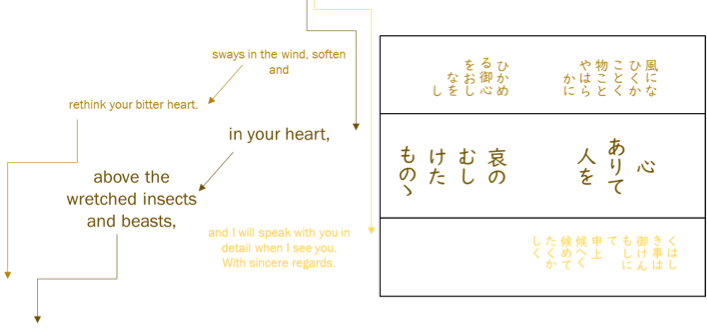

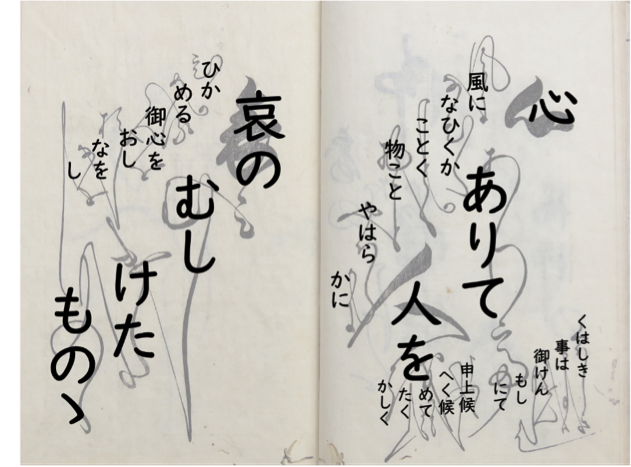

One of the conference’s most engrossing sessions was entitled ‘Writing with a Needle’. This panel brought together four textile artists to explore the intersection of writing and fabric from what one might call the sharp end. Alison Stewart, currently an art student in her final year at Chichester, described how her dyslexia had prompted her to invent ‘newsfabrics’, newspapers in which the words are covered up by patches of gingham that mimic the appearance of text at the same time as they occlude it. Sara Impey  brought in some of her quilts (illustrated here), stitched with texts that are often deliberately inconsequential and full of phatic elements, in order to subvert the sampler tradition in which stitched text has to earn its keep by being morally improving. Rosalind Wyatt’s work involves sewing immaculate facsimiles of handwritten texts onto garments that memorialize the lives of their wearers; she brought with her a running shirt that had belonged to Stephen Lawrence, together with one of his last school essays, which she was about to stitch-copy onto it. Lindsey Holmes continued this meditation on presence and absence by describing her work recreating pieces of costume at the Keats House. An exhibition about the poet’s relationship with Fanny Brawne allowed visitors to try on bodices, mitts and shoes closely resembling those worn in the period, thereby materially involving themselves in the past; and visitors responded enthusiastically to the invitation. The four papers generated rich discussion, with much reflection on the how the needle cuts against the rhythms of reading and unmoors words from their everyday business of signification.

brought in some of her quilts (illustrated here), stitched with texts that are often deliberately inconsequential and full of phatic elements, in order to subvert the sampler tradition in which stitched text has to earn its keep by being morally improving. Rosalind Wyatt’s work involves sewing immaculate facsimiles of handwritten texts onto garments that memorialize the lives of their wearers; she brought with her a running shirt that had belonged to Stephen Lawrence, together with one of his last school essays, which she was about to stitch-copy onto it. Lindsey Holmes continued this meditation on presence and absence by describing her work recreating pieces of costume at the Keats House. An exhibition about the poet’s relationship with Fanny Brawne allowed visitors to try on bodices, mitts and shoes closely resembling those worn in the period, thereby materially involving themselves in the past; and visitors responded enthusiastically to the invitation. The four papers generated rich discussion, with much reflection on the how the needle cuts against the rhythms of reading and unmoors words from their everyday business of signification.

Wearing Text

As Wyatt and Holmes reminded us, clothing is one of the most eloquent forms in which we encounter textiles. Several papers tackled it explicitly. Ben Cartwright (Cambridge) discussed the way that clothing ‘regestures’ the body, and emphasized the need to wear rather than merely to look at clothing from the past in order to understand its histories. In the Shetland and Norse communities that he studies, clothing at once makes inhabitation possible (it is proverbial that there is no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing!) and intimately conditions it. Patricia Pires Boulhosa (Cambridge) introduced us to a medieval Icelandic manuscript which had been cut up in the seventeenth century to be used as pattern pieces for making clothes. The leaves have now been reassembled again into a bound volume, but the resulting fragmentary object embodies the slippage between the stuff of the household and the stuff of the book.

Sally Holloway (Royal Holloway) reminded us of how clothing could be freighted with emotion, as she connected a variety of eighteenth-century birth and courtship tokens, including garments hand-made by courting sweethearts and pincushions made for the mothers of new-born babies. One example of which reads ‘Health to the little Stranger’. Give a pin-cushion before the birth and the labour will be painful (Holloway’s proverb was ‘more pins, more pain’). Here the emotional shades into the magical, gift into charm. And Mimi Yiu (Georgetown) unfolded the intriguing history of a particular stitch: blackwork, also known as the Spanish stitch or true-stitch. Probably originating in Mamluk Egypt,  blackwork retained its association with the foreign, and was described by John Taylor, the fabric- conscious water-poet, as coming from ‘Beyond the bounds of faithlesse Mahomet’. Despite contemporary suspicion and fear of both the Ottoman Empire and of Spain, Yiu argued, the stitch’s foreign origins added a fashionable frisson to elaborately worked collars and cuffs. Moving on to the terminology of ‘true-stitch’ (so called because the patterns appear the same on both sides of the fabric), Yiu argued that it was in the language of love that the stitch became more contested, as poets and playwrights deployed the term to argue not for women’s domestic constancy but for their fashionable fickleness.

blackwork retained its association with the foreign, and was described by John Taylor, the fabric- conscious water-poet, as coming from ‘Beyond the bounds of faithlesse Mahomet’. Despite contemporary suspicion and fear of both the Ottoman Empire and of Spain, Yiu argued, the stitch’s foreign origins added a fashionable frisson to elaborately worked collars and cuffs. Moving on to the terminology of ‘true-stitch’ (so called because the patterns appear the same on both sides of the fabric), Yiu argued that it was in the language of love that the stitch became more contested, as poets and playwrights deployed the term to argue not for women’s domestic constancy but for their fashionable fickleness.

Another paper that focused on clothing was given by Hester Lees-Jeffries (Cambridge). Here we were dazzled with a series of exquisite images, highlighting both the artistic skill and the intense domestic labour which went into producing the elaborate folds and pleats of Elizabethan and Jacobean costume. Meditating on the language of folding and unfolding in Shakespeare’s poems and plays, Lees-Jeffries encouraged us to consider connections between sensation and narrative movement and to restage the visual and verbal encounters invited or imagined by fabric and folds. Reminding us that the story of the play unfolds on stage or in reading but is folded (as paper) to form a readable book, she also raised intriguing questions of what happens within the fold, where material is not lost but concealed. Stories and patterns disappear and re-form in movements that mimic the structures of early modern literary composition.

As well as looking at what people wore, the conference also attended to the places they lived in, and in particular to the domestic sphere and the forms of production that emerged from it. Helen Smith (York) reassessed the association of domestic biblical embroideries with female oppression. Scrutinizing the terms in such embroideries were described in the period, she uncovered a strong association between the female needleworker and the God who ‘wrought’ his creation, alongside plentiful evidence for the affective force of stitched Scriptures. Leah Knight (Brock) described the reading practices of Anne Clifford in relation to the spaces, decoration, and management of her household, with particularly fascinating discussion of the choice of motifs and colours for the decor of the rooms in which reading might be located and the pinning up of texts upon their walls.

Telling by Hand

As this description will suggest, the proceedings of the conference were richly various; the discussion was lively and occasionally combative. It was appropriate, then, that our plenary speaker was someone whose own work is characterized by its omnicuriosity, as well as by the pungency of its multidisciplinary synthesis. Tim Ingold (Aberdeen) gave a talk entitled ‘Telling by Hand: Weaving, Drawing, Writing’, that offered an extraordinary series of reflections on the workings of the human hand. (Fittingly, he was framed throughout by the many hands of Richard Long’s mural ‘River Avon Mud, 1996’). Drawing on the work of Heidegger and Sennett, Ingold offered a sense of what we stand to lose in a push-button world, where the education of attention involved in ‘telling’ is sidelined in favour of prepackaged and articulated knowledge, or ‘joined-up thinking’. Somewhere near the heart of the paper was a breathtaking account of how you set about making a piece of string by hand. In its taut simplicity, its precision and clarity, Ingold’s plenary really did pull everything together.

(Aberdeen) gave a talk entitled ‘Telling by Hand: Weaving, Drawing, Writing’, that offered an extraordinary series of reflections on the workings of the human hand. (Fittingly, he was framed throughout by the many hands of Richard Long’s mural ‘River Avon Mud, 1996’). Drawing on the work of Heidegger and Sennett, Ingold offered a sense of what we stand to lose in a push-button world, where the education of attention involved in ‘telling’ is sidelined in favour of prepackaged and articulated knowledge, or ‘joined-up thinking’. Somewhere near the heart of the paper was a breathtaking account of how you set about making a piece of string by hand. In its taut simplicity, its precision and clarity, Ingold’s plenary really did pull everything together.

Report by Jason Scott-Warren. Thanks to Patricia Pires Boulhosa for photographs, and to Christopher Burlinson, Mary Laven, Hester Lees-Jeffries, Lucy Razzall and Helen Smith for their contributions to the text. The Impey quilt, from the Quilters’ Guild Collection, is reproduced by permission of Sara Impey. Photo: David Guthrie.

More images from the conference are available on the Centre’s Facebook page:

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Centre-for-Material-Texts-University-of-Cambridge/344548338909348

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Centre-for-Material-Texts-University-of-Cambridge/344548338909348

You can download the abstracts from the conference here…

& see also http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/the-needle-and-the-pen/

The Centre for Material Texts at Cambridge fosters research into the physical forms in which texts are embodied and circulated, and the ways in which those forms have interacted with literary cultures and historical contexts. Based in the Faculty of English, it provides a focus for editorial and bibliographical work, and for critical, theoretical and historical projects of many kinds. The CMT fosters the study of a wide variety of media–from spoken words to celluloid, from manuscript to XML–and brings together academics and postgraduates from a range of faculties and departments across the University. This is a forum for starting new conversations which will push back the boundaries of knowledge in one of the most exciting areas of humanities research.

The Centre for Material Texts at Cambridge fosters research into the physical forms in which texts are embodied and circulated, and the ways in which those forms have interacted with literary cultures and historical contexts. Based in the Faculty of English, it provides a focus for editorial and bibliographical work, and for critical, theoretical and historical projects of many kinds. The CMT fosters the study of a wide variety of media–from spoken words to celluloid, from manuscript to XML–and brings together academics and postgraduates from a range of faculties and departments across the University. This is a forum for starting new conversations which will push back the boundaries of knowledge in one of the most exciting areas of humanities research. Writing Britain 500-1500 (2014)

Writing Britain 500-1500 (2014)

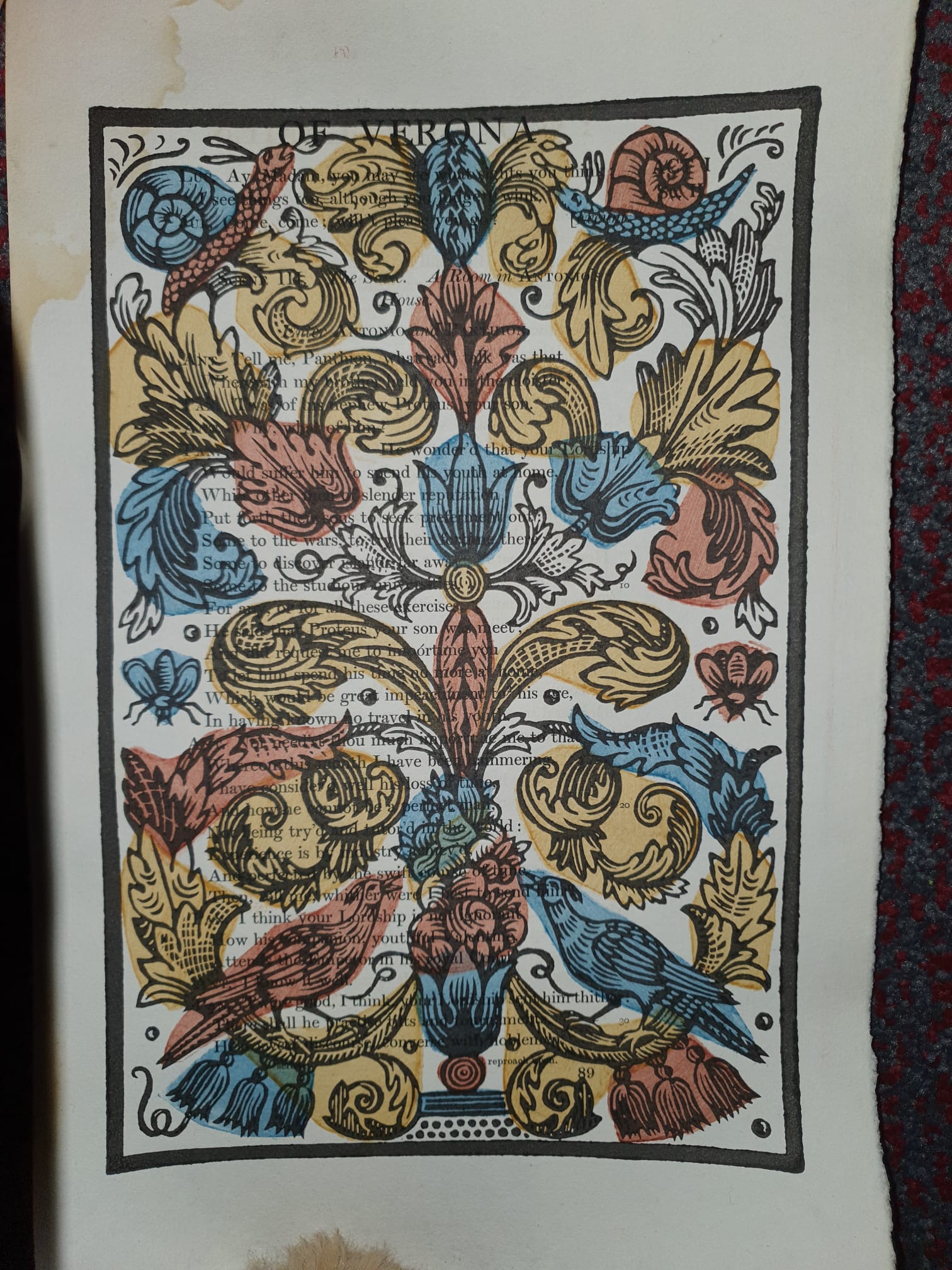

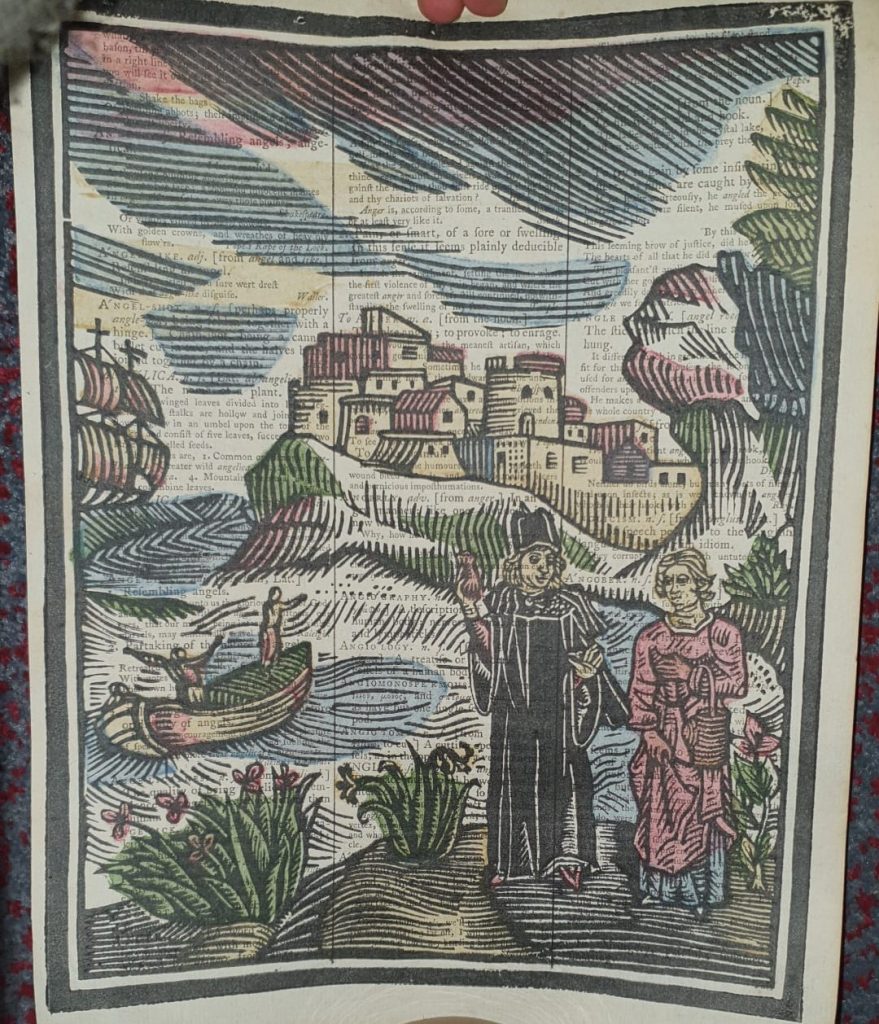

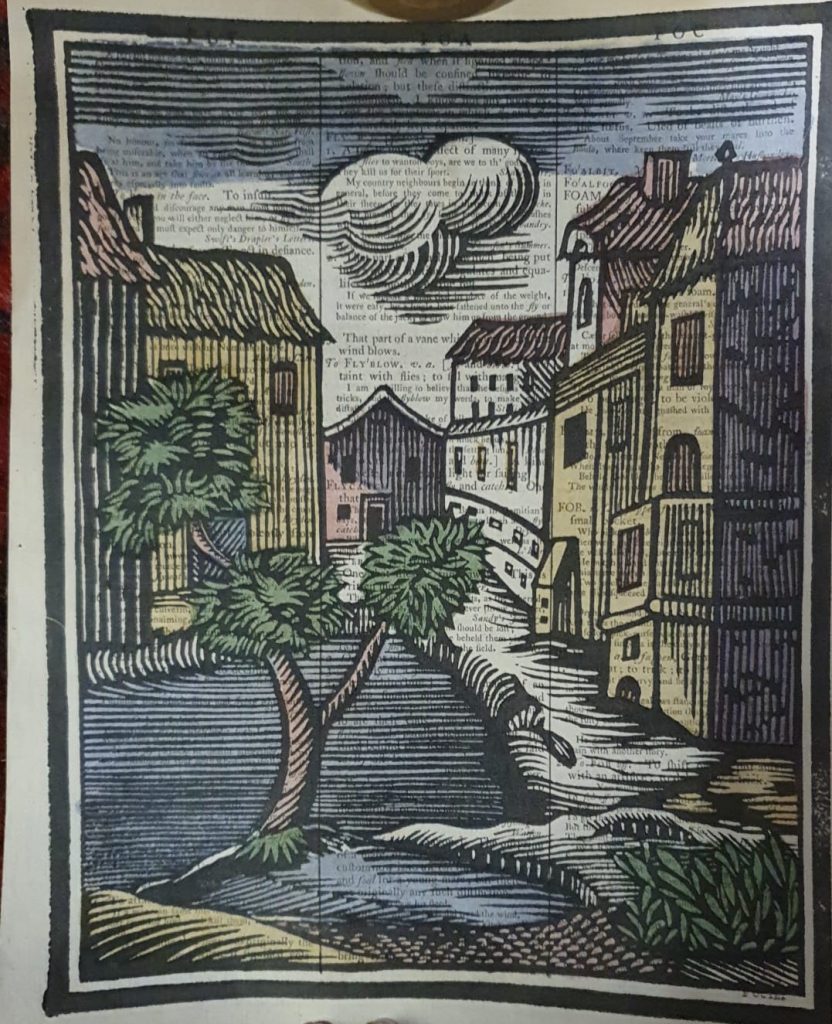

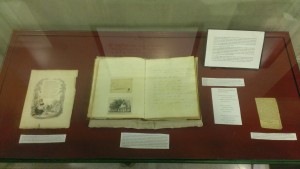

A backwater lay-by off the M5, Junction 24, three days before Christmas. A covert exchange of an unknown document, protected only by an iPad case, occurs between man, whippet and young woman. Shady as it may seem, this is not the stuff of reconnaissance but curation. This nineteenth-century commonplace book replete with beautiful illustrations, kindly donated by John and Caroline Robinson, now lies in situ on the first floor of the English Faculty, at the heart of the inaugural exhibition of the Centre for Material Texts. The exhibition, curated by myself and my MPhil colleagues on Dr Ruth Abbott’s Writers’ Notebooks course, focuses on commonplace books and the ways in which they acted as repositories for the recording of daily life in the nineteenth century. From passages of the Bible to Byron, musings on God to sketches of the family dogs, the commonplace book offered a powerful collective storehouse for the miscellanies and medleys of material that amassed at the center of communal family life.

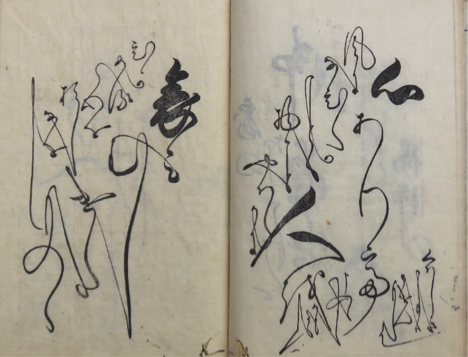

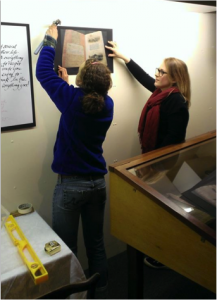

A backwater lay-by off the M5, Junction 24, three days before Christmas. A covert exchange of an unknown document, protected only by an iPad case, occurs between man, whippet and young woman. Shady as it may seem, this is not the stuff of reconnaissance but curation. This nineteenth-century commonplace book replete with beautiful illustrations, kindly donated by John and Caroline Robinson, now lies in situ on the first floor of the English Faculty, at the heart of the inaugural exhibition of the Centre for Material Texts. The exhibition, curated by myself and my MPhil colleagues on Dr Ruth Abbott’s Writers’ Notebooks course, focuses on commonplace books and the ways in which they acted as repositories for the recording of daily life in the nineteenth century. From passages of the Bible to Byron, musings on God to sketches of the family dogs, the commonplace book offered a powerful collective storehouse for the miscellanies and medleys of material that amassed at the center of communal family life. The unconventional method through which our exhibition materials were acquired proves apropos, given the unusual conditions under which the birth of our interest in commonplace books occurred. In another intrepid motorway adventure: a six hour, 250-mile minibus journey (nobly helmed by Ruth Abbott) with eight complete strangers, our group’s first weekend in Cambridge, was in fact spent in Grasmere, Cumbria working at the Wordsworth Trust. Guided by Ruth and curator Jeff Cowton we spent a full two days nestled in the archive, immersed in manuscripts and the materials which made them. It was a weekend stuffed with stuff. We created Thomas Bewick prints on a nineteenth-century printing press. We learned how to bind books on a sewing frame. Quills were carved and inks were made. Paste was pressed from pulp into paper (with the aid of a craftsman’s deckle and an improvised flattening dance on top of it). In a flurry of high spirits, fumbling with spirit-levels, our exhibition on the Wordsworth family commonplace books was installed.

The unconventional method through which our exhibition materials were acquired proves apropos, given the unusual conditions under which the birth of our interest in commonplace books occurred. In another intrepid motorway adventure: a six hour, 250-mile minibus journey (nobly helmed by Ruth Abbott) with eight complete strangers, our group’s first weekend in Cambridge, was in fact spent in Grasmere, Cumbria working at the Wordsworth Trust. Guided by Ruth and curator Jeff Cowton we spent a full two days nestled in the archive, immersed in manuscripts and the materials which made them. It was a weekend stuffed with stuff. We created Thomas Bewick prints on a nineteenth-century printing press. We learned how to bind books on a sewing frame. Quills were carved and inks were made. Paste was pressed from pulp into paper (with the aid of a craftsman’s deckle and an improvised flattening dance on top of it). In a flurry of high spirits, fumbling with spirit-levels, our exhibition on the Wordsworth family commonplace books was installed. Like the chain lines and watermarks we spent the days studying in manuscripts, through curatorial collaboration we had impressed a profound mark on each other. The silence, sky and space of the Lakes and our collective academic endeavour had bound us together as tightly as the spines of the nineteenth-century treasures that lay on the archive’s shelves. What was particularly pertinent in creating this exhibition, born into being from deeply felt fellow-feeling from all parties, was that it chronicles and encourages the communal sharing of thought. The addition of our modern commonplace book to the display invites exhibition-goers to participate in shared forms of notetaking, to add their scraps and fragments of experience, their inmost thoughts, their favourite quotations and aid the creation of a beautiful, diverse collective text.

Like the chain lines and watermarks we spent the days studying in manuscripts, through curatorial collaboration we had impressed a profound mark on each other. The silence, sky and space of the Lakes and our collective academic endeavour had bound us together as tightly as the spines of the nineteenth-century treasures that lay on the archive’s shelves. What was particularly pertinent in creating this exhibition, born into being from deeply felt fellow-feeling from all parties, was that it chronicles and encourages the communal sharing of thought. The addition of our modern commonplace book to the display invites exhibition-goers to participate in shared forms of notetaking, to add their scraps and fragments of experience, their inmost thoughts, their favourite quotations and aid the creation of a beautiful, diverse collective text. Speaking to other students who have visited Grasmere, at a recent meeting with the Wordsworth Trust at London’s Brigham Young Institute, I further realised the true powerful potential of the material. Through awe-filled eyes, each sentence suffused with a quasi-religious fervour, they recounted the moment they were allowed to see a first edition of Lyrical Ballads and handle Dorothy Wordsworth’s real notebooks. In fact, the Wordsworth Trust’s website proudly proclaims ‘Visit the Wordsworth Museum to see Dorothy’s actual notebooks’. This is something our group reflected upon as we sat around Wordsworth’s ‘actual’ fire in Dove Cottage, reading his poems, souls stirred by the transcendent beauty of breathing life back into words where they were first brought into being. In curating this exhibition, in Grasmere and in Cambridge, and through Ruth Abbott’s phenomenal notebooks course we have relearnt the overwhelming magic of the material, the ability to encounter and interact with the ‘actual’. It is in this kind of engagement with ‘actual’ manuscripts, notebooks and papers that ‘with an eye made quiet by the power/Of harmony, and the deep power of joy, / We see into the life of things’.

Speaking to other students who have visited Grasmere, at a recent meeting with the Wordsworth Trust at London’s Brigham Young Institute, I further realised the true powerful potential of the material. Through awe-filled eyes, each sentence suffused with a quasi-religious fervour, they recounted the moment they were allowed to see a first edition of Lyrical Ballads and handle Dorothy Wordsworth’s real notebooks. In fact, the Wordsworth Trust’s website proudly proclaims ‘Visit the Wordsworth Museum to see Dorothy’s actual notebooks’. This is something our group reflected upon as we sat around Wordsworth’s ‘actual’ fire in Dove Cottage, reading his poems, souls stirred by the transcendent beauty of breathing life back into words where they were first brought into being. In curating this exhibition, in Grasmere and in Cambridge, and through Ruth Abbott’s phenomenal notebooks course we have relearnt the overwhelming magic of the material, the ability to encounter and interact with the ‘actual’. It is in this kind of engagement with ‘actual’ manuscripts, notebooks and papers that ‘with an eye made quiet by the power/Of harmony, and the deep power of joy, / We see into the life of things’. Through our immersion in the material practices from which texts develop, we learnt to cultivate a fresh appreciation for the ways in which literature is embodied and presented. The afterlives of the work we have done with these exhibitions, and the study of notebooks and manuscripts in general, like Wordsworth’s River Duddon, flow on endlessly. From future PhD projects to the reinstallation of the commonplace book exhibition in Cambridge ‘Still glides the Stream, and shall for ever glide;/The Form remains, the Function never dies’. We hope that in this latest reimagining of our display, we encourage others to see the beautiful potential in collective interaction with note-taking practices. In doing so, our work continues ‘to live, and act, and serve the future hour’.

Through our immersion in the material practices from which texts develop, we learnt to cultivate a fresh appreciation for the ways in which literature is embodied and presented. The afterlives of the work we have done with these exhibitions, and the study of notebooks and manuscripts in general, like Wordsworth’s River Duddon, flow on endlessly. From future PhD projects to the reinstallation of the commonplace book exhibition in Cambridge ‘Still glides the Stream, and shall for ever glide;/The Form remains, the Function never dies’. We hope that in this latest reimagining of our display, we encourage others to see the beautiful potential in collective interaction with note-taking practices. In doing so, our work continues ‘to live, and act, and serve the future hour’. Megan Beech, MPhil Modern and Contemporary Literature

Megan Beech, MPhil Modern and Contemporary Literature