Over the centuries, writers have tried to represent linguistic failure better. There has been a persistent deepening of efforts to get closer to real speech, with its disfluencies, false starts and interruptions. Peculiar as it may sound, an unfinished sentence can, in its own way, be as much of a literary accomplishment as a couplet.

Over the centuries, writers have tried to represent linguistic failure better. There has been a persistent deepening of efforts to get closer to real speech, with its disfluencies, false starts and interruptions. Peculiar as it may sound, an unfinished sentence can, in its own way, be as much of a literary accomplishment as a couplet.

Punctuation has been fundamental in this aspiration towards the depiction of ordinary speech. The focus of my work has been to trace the development of a punctuation mark that emerged specifically to denote interruptions, hesitations and other forms of incompleteness. This is the history of … a symbol that became notorious in the early twentieth century as a sign of the elusive and generally vague…

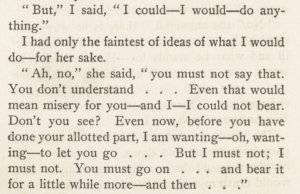

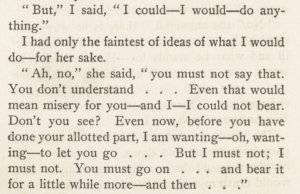

The collaborative work of Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford at the turn of the twentieth century provides an interesting study in the rise and resulting disapproval of the dot, dot dot. When working together on The Inheritors (1901) Ford and Conrad aimed to capture ‘the sort of indefiniteness that is characteristic of all human conversations, and particularly of all English conversations that are almost always conducted entirely by means of allusions and unfinished sentences.’[i] The Inheritors contained over four hundred instances of … though it was a relatively short novel.

Joseph Conrad and Ford M. Hueffer, The Inheritors: An Extravagant Story (London: William Heinemann, 1901), p. 232; CUL. Misc.7.90. 468

The critics didn’t like this. Conrad wrote in a letter about The Scotsman’s review, ‘It is the typographical trick of broken phrases: … that upsets the critic. Obviously. He says the characters have a difficulty of expressing themselves; and he says it only on that account’ (to Ford Madox Ford, 11 July 1901).

That critics could be upset in 1901 at characters speaking in broken phrases is surprising, to say the least. Marks of ellipsis had been used in English print since the end of the sixteenth century to indicate unfinished sentences. Dots, dashes and asterisks had been prevalent in print to mark inarticulacy for centuries.

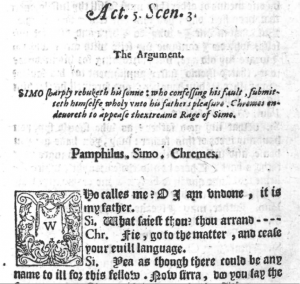

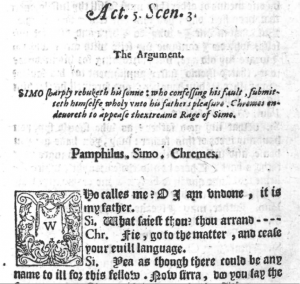

Drama was especially important in the evolution of the ellipsis. This is perhaps to be expected, as drama is the literary form that is connected in the most concentrated way with speech as it is spoken. In 1588, what I believe to be the earliest marks of ellipsis in English drama appeared in a translation of Terence’s Andria. On three occasions, a series of hyphens are used to suggest interruption — or self-interruption. This was a simple but brilliant innovation. The mark worked as a form of stage direction, providing, at a glance, information about delivery, possibly offering space for gesture, and suggesting a great deal about characterization.

Terence, Andria, translated by Maurice Kyffin (London, 1588); © The British Library Board, C.13.a.6 sig. I4r.

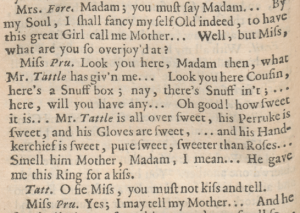

The mark quickly caught on, with ellipses becoming a common feature of play texts. Ellipsis marks appear in some of the early printed plays by Shakespeare and in abundance in the work of Ben Jonson.

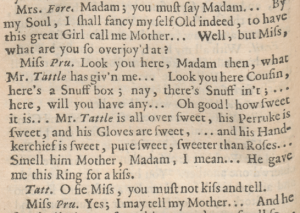

It is difficult to ascribe agency for these markings absolutely in this period. Printers often took responsibility for punctuation, and, at the very least, the choice of ellipsis mark may have been determined by what a printer had available. By the eighteenth century, alongside dashes and hyphens, series of dots began to be seen in works written in English, most probably with the influence of developing continental practice. Hyphens, dashes and dots would largely have been understood as equivalent marks. Dot, dot, dot, had yet to develop its own strongly recognizable set of connotations and attributes.

William Congreve, Love for Love: A Comedy (London [The Hague]: [for Thomas Johnson], 1710), p. 52; CUL, Brett-Smith.b.9

It was in the novel that these marks of ellipsis proliferated most spectacularly, taking on new representative dimensions. Novelists imitated play texts by punctuating their dialogues with interruptions and hesitations. Elocutionists took notice of this, debating the efficacy of these marks in aiding the transcription of the human voice. But novelists also used the same punctuation marks to depict failures of voice more fundamentally, as ellipsis marks in narrative passages presented questions about narrative authority and representational ability. Ellipsis marks were also enlisted in novelistic realizations of human interiority, including its incoherencies and blanks. Dots and dashes became wildly popular in the pan-European language of sensibility of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, where they became tokens of emotion and passion, burgeoning across lines and even pages, acting often as shortcuts to the meaningful.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the variant marks of ellipsis began to take on different roles, with the dash becoming especially popular as a fully accredited mark of punctuation. Grammarians finally acknowledged the dash as one of the primary marks of punctuation in the late 1700s, with Lindley Murray’s extraordinarily successful 1795 English Grammar even being described by one commentator as having legalized the dash.[ii]

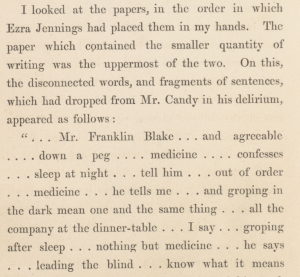

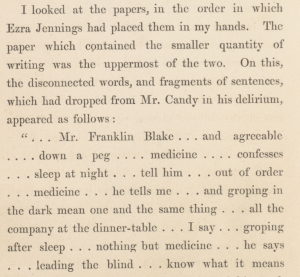

Changes in the printing industry over the nineteenth century also led to increasingly uniform methods of punctuation, one reason being that common practice facilitated augmented rates of book production. Guides for printers encouraged standardized punctuation and the dash proved versatile in marking (among other things) incomplete sentences, pauses and changes in tone. Dot, dot, dot, by contrast was to serve mainly a citationary function, indicating material omitted from quotations. However, for literary writers at least, the marginalized identity of the … made it an interesting and often unsettling resource in contradistinction to the ubiquitous dash. Wilkie Collins in his pioneering detective novel, The Moonstone (1868), deploys series of dots in an orthodox fashion to indicate missing words in a transcription, but he imbues those omissions with the mysterious qualities of the unconscious mind.

Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone. A Romance (London: Tinsley Brothers, 1868), vol. 3, p. 148; CUL, Nov.143.69-71

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, George Meredith was attempting to articulate minute changes in human sensation by means of different styles of ellipsis. In The Tragic Comedians (1880) Meredith even notates different ways of ‘thinking without language’, by contemplating subtle variations between ‘tentative dots’ and the dash.

In an essay on ‘The Psychology of Punctuation’ published in 1948, E.L. Thorndike commented, not on the presentation of fictional psychologies by means of punctuation, but on what punctuation can reveal about the psychological processes at work when we read and write. A large part of his essay concerns the invisibility of punctuation. Writing about the remarkable rise of ‘…’ in twentieth-century fiction, Thorndike notes that though he was often in the company of dot, dot, dot as a reader of George Meredith, Edith Wharton and others, ‘Not until I found it abounding in my counts of punctuation, did I ever think anything about it’.[iii] Thorndike testifies to the extraordinary ways in which what is in front of us on the printed page can remain unseen in the reading process. But such invisibility is curiously apt with respect to dot, dot, dot, which mediates between the suppressed and the manifest and which emerged, long before George Meredith was writing, to make silence (almost) seen.

Anne Toner

[i] Ford Madox Ford, Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance (London: Duckworth & Co., 1924), p. 135.

[ii] Justin Brenan, Composition and Punctuation Familiarly Explained (London: Effingham Willson, 1829), p. 68.

[iii] E. L. Thorndike, ‘The Psychology of Punctuation’, American Journal of Psychology, 61 (1948), 222-8, pp. 225-6.

Speakers will include: Richard Fisher (former Managing Director of Academic Publishing at Cambridge University Press), Rupert Gatti (Faculty of Economics/Open Book Publishers), Anne Jarvis (University Librarian, Cambridge University Library), Danny Kingsley (University of Cambridge, Office of Scholarly Communication), Peter Mandler (Faculty of History, President of the Royal Historical Society), Samantha Rayner (Senior Lecturer in Publishing, UCL), Alison Wood (Mellon/Newton Trust Postdoctoral Fellow, CRASSH).

Speakers will include: Richard Fisher (former Managing Director of Academic Publishing at Cambridge University Press), Rupert Gatti (Faculty of Economics/Open Book Publishers), Anne Jarvis (University Librarian, Cambridge University Library), Danny Kingsley (University of Cambridge, Office of Scholarly Communication), Peter Mandler (Faculty of History, President of the Royal Historical Society), Samantha Rayner (Senior Lecturer in Publishing, UCL), Alison Wood (Mellon/Newton Trust Postdoctoral Fellow, CRASSH).