From copying in the scriptorium to coding on the computer: understanding the book as support

July 22nd, 2020Gallery; Jason Scott-WarrenJustine Provino is embarked on a PhD in the Faculty of English at Cambridge. Here she describes her unusal and challenging project.

In normal times, writing a PhD on how libraries can preserve and facilitate access to self-destructive books might seem strange enough. The duty of these ancient institutions is to care for the works that they gather on their shelves, and to pass the information they enshrine from one generation of readers to the next. What would they make of a book that has been designed not to survive?

In the time of Covid-19, my PhD research has turned into a full-scale practical test on the work of the library in framing written culture. The physical thresholds of our cultural heritage institutions have become impossible to cross, locking away all those books that were bound so as to last, but which are also bound to decay, like all organic matter. One might mischievously assert that this state of affairs is optimal for preservation: all of the books are shielded from the touch of readers, enjoying the absence of the stress that afflicts their spines every time they are opened. But being untouched, for a book, also means that it is not fulfilling its main function in our society: the transmission of content through the process of reading. The transfer of knowledge accelerates the decline of the book as a container (torn pages, distressed covers), as we know; sometimes, it can even spell the destruction of the book, as books are ‘read to death’. Books put up different degrees of resistance to their assailants—the flimsier examples might be said to have ‘built-in obsolescence’, falling apart at the first opportunity. Unbound products of the press, such as newspapers are date-stamped in the full knowledge of their own ephemerality. But few books actively seek their own ends.

So what is a self-destructive book? Why was it even made? Where is it? Can it be seen and touched? Why would one wish to preserve and access such a counter-intuitive bibliographical artefact in a library?!

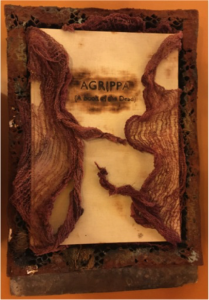

A self-destructive book is just that: a book intended by its makers to self-destruct. My PhD case study, the 1992 American artists’ book, Agrippa (a book of the dead), is so far the only example of its kind. But my research keeps me on the lookout for instances that would prove this claim wrong, and I would be delighted to be contradicted as soon as this blog is posted. Agrippa was the product of a collaboration between the publisher Kevin Begos Jr, the writer William Gibson, and the artist Dennis Ashbaugh. Though many artists’ books have involved an element of destruction, from John Latham’s Skoob Towers, burning books in the 1960s, to Stephen Emmerson’s latest translation of Rilke in spores, in which a fungus grown on the book’s cover feeds from the paper and ink, the materials in these books existed before they were re-used in a process of creative destruction. By contrast, Agrippa was made to self-destruct and self-erase before it was turned into a bound object.

Begos Jr/Gibson/Ashbaugh, Agrippa (a book of the dead), 1992. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rec. b. 38/Rec. a. 25, copy wrapped in shroud and enshrined.

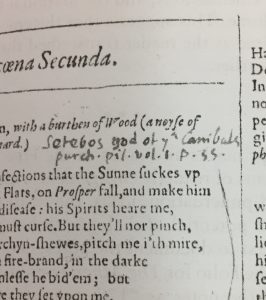

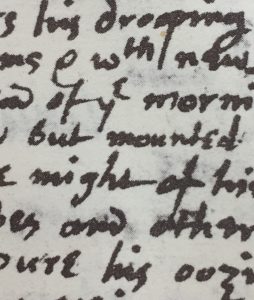

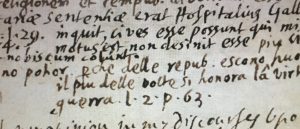

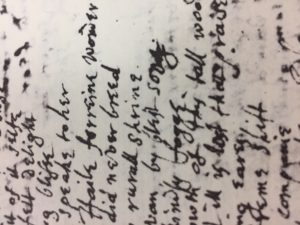

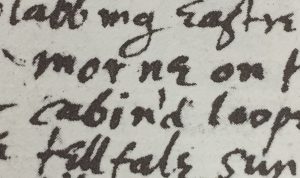

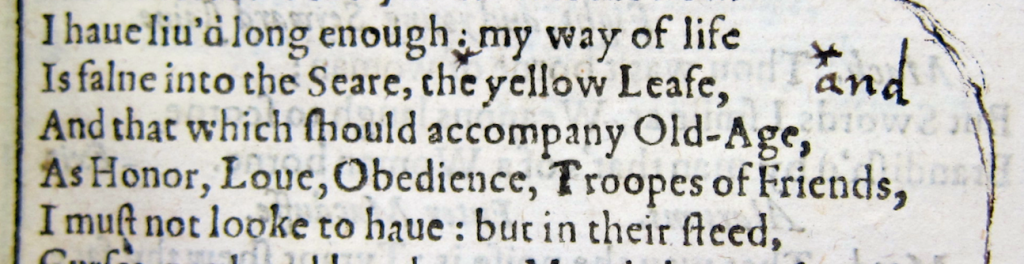

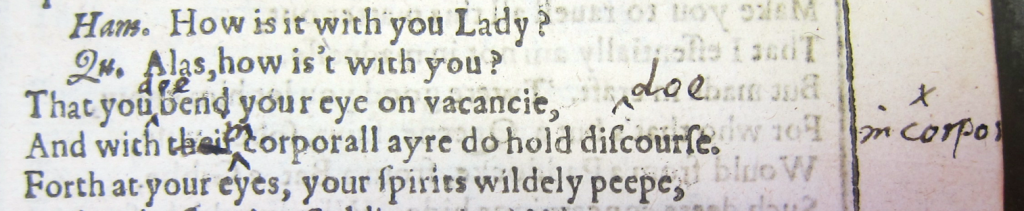

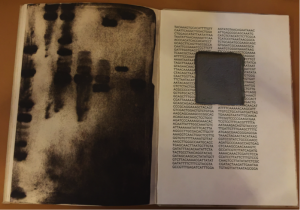

Inside the book, Ashbaugh’s printworks represent vintage technologies (a pistol, a Bell telephone), and these images are overprinted onto a transcription of the DNA of the fruitfly. This insect is usually associated with ‘something rotten’, and the printmaking technique itself is rooted in decay: a first layer of aquatint etching is overprinted with unfixed-toner carbon ink. This second layer necessarily offsets onto the next page, and it also moves from its support as the page is being turned by the reader, or as the reader touches the top layer of the image; over time, it disappears. Accompanying this artwork is Gibson’s literary contribution, an autobiographical poem about his family and his emergence as a writer. The poem is digitally encrypted on a Mac floppy disk encoded to self-destruct as being read. The floppy disk is inserted into a hollowed cavity which is carved into the centre of the analogue textblock of the book. It was encrypted so as to be playable only once—after a single ‘performance’ of the poem, the disk would become unreadable, echoing the physical decay of the images.

Begos Jr/Gibson/Ashbaugh: aquatint etching with an overprint of a pistol diagram. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rec. c. 98, facing title page.

Not all of the forms of self-destruction in Agrippa were ‘intended’. The composite multi-media confection is encased in a presentation fibre-glass box, the interior of which is made of cardboard covered in an as-yet-unidentified paint. These elements are very likely to offgass acidic components onto the book, thus contributing to the oxidation – and alteration both in composition and aspect – of Agrippa’s organic materials (the stiffening of its textblock, the yellowing of its cloth-covered boards). On the exterior, this box takes the shape of an early century Kodak photo-album labelled ‘Agrippa’. This makes it a simulacrum of the photo-album Gibson found in his family home, filled with his late father’s and grandfather’s photographs. This vintage artefact was the germ of his poem about the dead, and gave the collaborative artist’s book its title.

Begos Jr/Gibson/Ashbaugh. Fibre-glass cover imitating vintage photo-album with label ‘Agrippa’; presentation box accompanying the deluxe edition of Agrippa. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rec. a. 25.

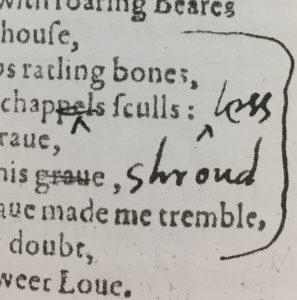

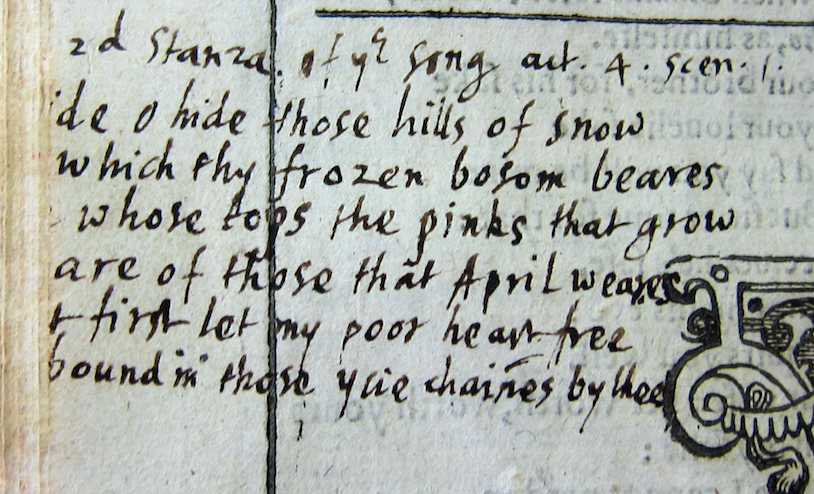

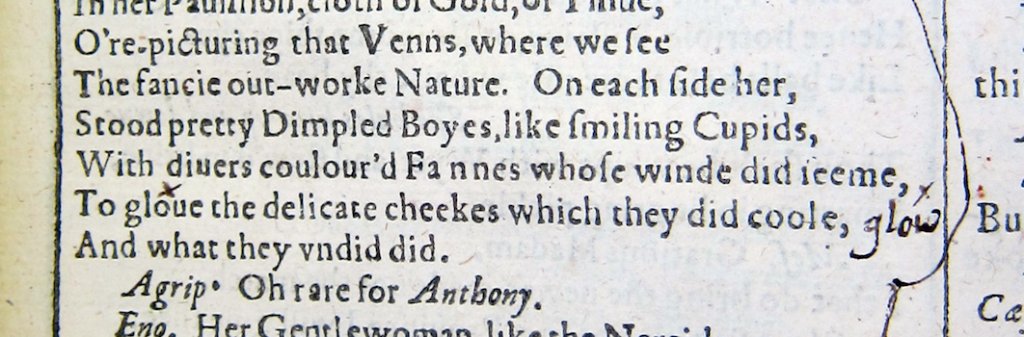

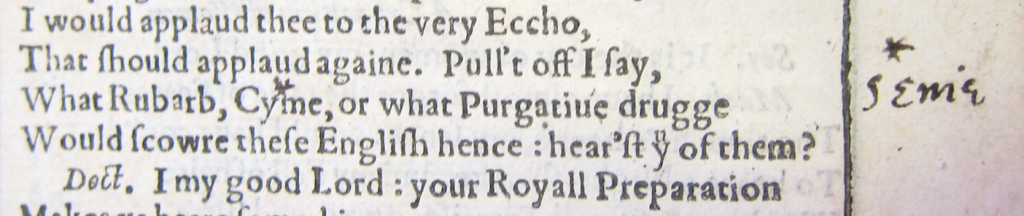

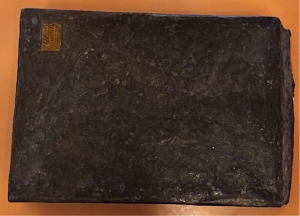

Begos’s archive on Agrippa, housed at the Bodleian Library, retraces the creation of the book and the reaction of the public from 1992 to 2005. This archive is accompanied by a deluxe- and a small-edition copy of Agrippa, which materially evidence some of the many phases in the making of the self-destructive book. The deluxe edition is missing its floppy disk and has no ‘disappearing images’; the small edition is not visibly lacking any elements. Both editions have presentation boxes made of acidic materials. As a book conservator by training, these copies present me with both an ethical and practical challenge. They were made to trigger our common – but quixotic – idea of the book-object as a permanent support. Agrippa presents us with the material reality that a book is an object that necessarily evolves over time, and we have to take into account the book’s evolution in order appropriately to care for and to preserve its informational content. The most ancient form of codex and its hardware (chains, clasps) and the latest e-book software have in common the fact that they are transferable supports, generated by copying in the scriptorium or coding on the computer. They can also be erasable supports, whether they are palimpsests or data files. Agrippa’s makers remind us that we quickly become oblivious to the materiality of a text as long as it ‘does the job’, forgetting that it is vital to the communication of its content. Agrippa reveals a lot about the relationship between our idealised vision of the book and its material reality.

Begos Jr/Gibson/Ashbaugh, deluxe edition of Agrippa. Aquatint etching, without disappearing image, facing a hollowed cavity carved in the textblock that is missing its floppy disk. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rec. b. 38.

But can Agrippa be preserved? Strikingly, it preservation started the moment it was released. After Begos advertised it, highlighting its ephemerality, Gibson’s poem was hijacked via a secret recording, made during the public reading of the text from a computer screen at the time of Agrippa’s launch on December 9th 1992 (the recording is now available on YouTube). In parallel to this public intervention, Begos himself gathered and preserved Ashbaugh’s artist’s proofs and his experiments in the process of overprinting, together with information on the making of the fibre-glass presentation box, and the contract for the encryption code; these items are all in the Bodleian archive. The library is now the framework that allows this network of digital and physical data to be reconnected, allowing the researcher to glimpse the unfolding process of a one-off, entirely unrepeatable performance.