I’m currently working on a doctoral thesis on an analysis and editing of a 15th century dictionary written by the school-master, chronicler and theologist Dietrich Engelhus (ca. 1362-1434). The dictionary contains lemmata in both Latin and Greek (using the Latin alphabet), followed by a multitude of explanations such as definitions, translations into Middle Low German, examples of use, derivations and grammatical information.

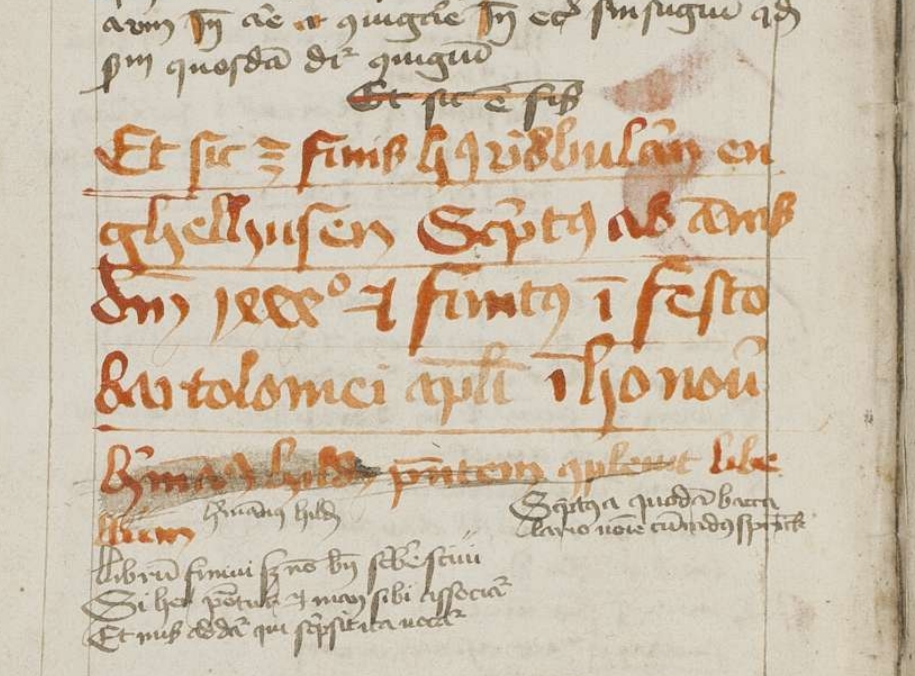

Cod. Guelf. 956 Helmst., 221v

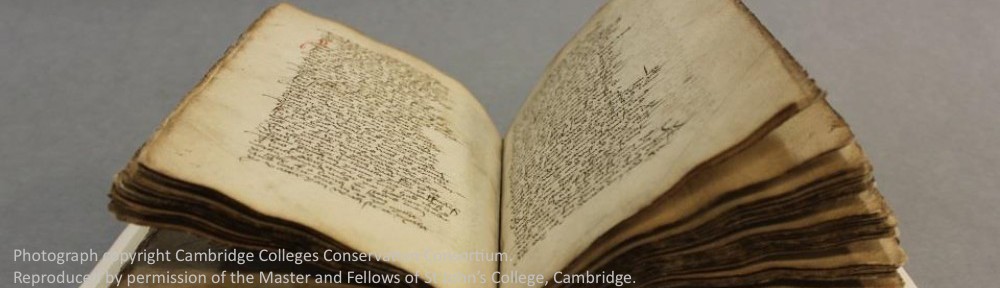

My research is based on two out of 19 surviving manuscript copies – Cod. Guelf. 720 Helmst. and Cod. Guelf. 956 Helmst. – whose unusually detailed colophons mention not only the two scribes’ names (Ludolf Oldendorp and Hermann von Hildesheim) and the teacher’s name (Konrad Sprink), but also indicate the same completion date (24th August 1444) and even the exact completion time (‘hora tercia post prandium’ – in the third hour in the morning). Based on this, scholars assume that Konrad Sprink dictated the dictionary to his two students as part of their education.

I am currently in the process of transcribing the two manuscripts and encoding them

in XML according to TEI standard (read more about some of the challenges I’m facing). Once the edition is finished it will be published online in the Wolfenbütteler Digitale Bibliothek (WDB).

The reason for choosing the digital approach is twofold: (1) I want the rich content

of the dictionary to be openly accessible and re-usable by other scholars and (2)

the encoding will enable me to answer research questions and support theories by means

of statistical analysis. Through the use of XPath queries and regular expressions,

I am able to make significant statements on quantities, frequencies and nesting hierarchies of explanations or specific strings. First statistical projections show, for example, that – in accordance with claims in the dictionary’s prologue – German translations are the second most common explanations after definitions. However, they also show that the number of Greek lemmata is much smaller than expected and only amount to about 6%. Other queries reveal noticeable preferences for either one or other orthographicvariant. For example, one scribe spells German words with ‘gh’ whereas the other prefers ‘g’, such as in ‘seghel’ vs. ‘segel’.

Some of the research questions I am hoping to answer in my thesis are as follows.

Which parts of the dictionary are most prone to orthographic variations? Are the marginalia

independent additions from other dictionaries, or corrections of the text at hand?

Are the identical colophons the only evidence to support the assumption of the manuscripts having been dictated, or are there other indicators? (Yes, there are other indicators and you can read more here.) Can the entries be sorted into distinct categories according to the structure of their explanations, do they follow regularities? How accurate are cross-references within the dictionary?

While there is ample opportunity here for other worthwhile studies (for example, the

development of a profile of the scribes’ spelling habits based on their individual

use of abbreviations), such analysis lies beyond the scope of this thesis. Furthermore,

since my focus is on the German equivalents and the general lexicographic analysis,

peculiarities of the Latin lemmata and explanations can only be touched upon.

Jennifer Bunselmeier, DPhil student, Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, University of Oxford