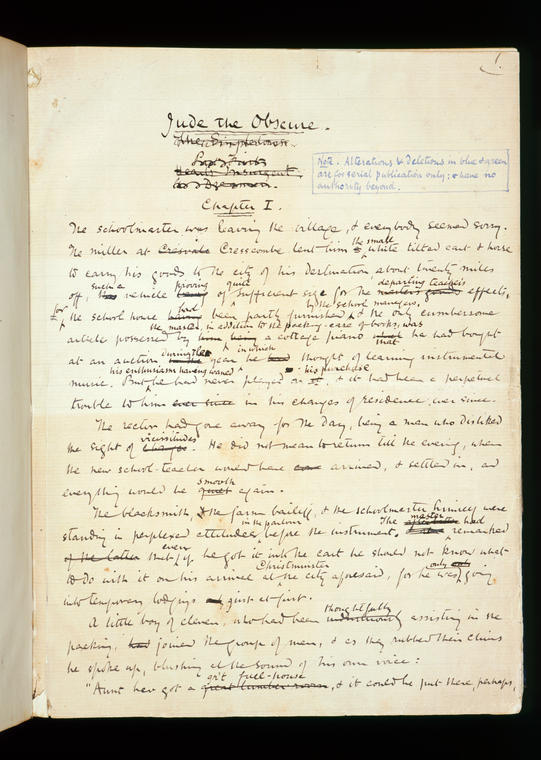

Thomas Hardy, Jude the Obscure. © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum holds both the original manuscript and first edition proofs for Thomas Hardy’s novel Jude the Obscure (Object Numbers MS 1-1911 and PB 9-2008). The novel was published in 1895 and follows the tragic tale of Jude Fawley, whose impassioned ambition to become a scholar is repeatedly thwarted by a troublesome blend of social impediments and regrettable personal decision-making. The novel transpired to be Hardy’s swansong in literary fiction, and is an astonishingly rich vision of the troubled philosophical and political conditions in the fin de siècle.

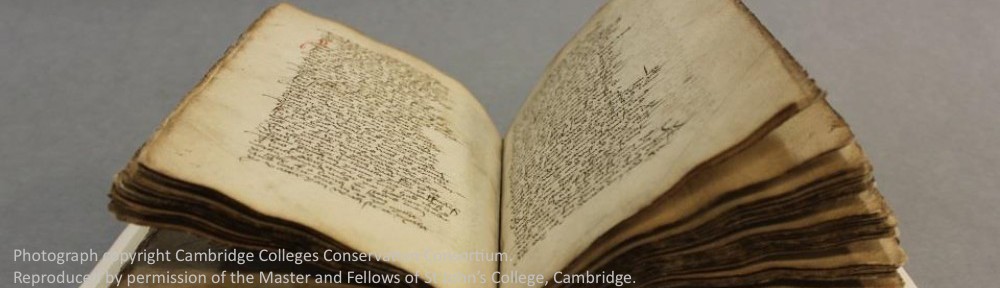

Hardy gifted the autographed manuscript to the Fitzwilliam in 1911, having struck up a relationship with the museum’s then director, Sydney Cockerell. In 2008, the museum added to this collection by purchasing the working proofs for the first edition, which contain Hardy’s final emendations before the novel was printed. Other than minor alterations, the proof is true to the manuscript. However, the proof ignores text scribed in blue ink in the original manuscript constituting edits only to be included in the ‘toned down’ version of the novel serialised in the Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. The manuscript shows the novelist in full command of his literary powers, and presents a reader with a rare opportunity to study the evolution of this modern classic. Careful attention to edits, elisions and additions bear fascinating insights in to the evolution of this text.

The Elision of Mark Pattison

One such example of the novel’s evolution within the manuscript may be found in a curious elision of Mark Pattison from the retinue of ghosts that haunt Jude’s ‘fancy’ at Christminster. Famously, when Jude arrives in Christminster, a university town on the outskirts of Wessex, he is haunted by visions of the ‘great men’ of the University of Oxford; he spends a great deal of time recalling their words while meandering among the town’s ‘cloisters and quadrangles’. In the manuscript, one example of these ghosts was the Rector of Lincoln College and liberal reformer, Mark Pattison, but the name has been struck through twice, and thus omitted from the proof. The famous liberal reformer and antagonist to the Oxford Movement is removed from the novel’s historical backdrop.

The spectres in the haunting scenes are primarily figures associated with the Oxford Movement—a theologically minded faction at the University of Oxford who argued for the reinstatement of a number of old church values in both the Anglican Church and the university’s governance. Jude’s reverence for John Henry Newman, the Movement’s most iconic apologist, imbues Jude’s impression of Christminster with a mediaeval idyll of ecclesiastical tranquility.

Incorporating Newman’s ideas within Jude is not without paradoxical implications, however. Newman’s Oxford is seen as beatifically romantic, but also politically closed and provincial. Newman is certainly not a voice seeking to break down the high walls for the likes of young Jude, and many reformers such as Pattison saw in Newman a staunch defender of an elitist status quo.

The debates surrounding university reforms were predominantly framed between the perceived retrogression of the Oxford Movement and modernising liberal reformers such as Mark Pattison. Whilst the book was written during the 1890s, the novel itself is set between the 1860s and 70s. Following parliamentary reforms to Oxbridge constitutions during the period, changes were made to modernise university governance and create a culture of meritocracy in the selection of fellows and students.

Hardy was aware of changes to open Oxbridge to the aspirant classes, having attended a lecture delivered by his friend Horatio Moule on the ‘Middle Class Examinations’ in 1858. There is a good deal of evidence in the author’s Literary Notebooks, correspondence and biographical accounts to show that unlike Jude, Hardy himself held a nostalgic but profoundly suspicious regard for Newman’s ideal university. Jude, however, uncritically imbibes the Oxford Movement’s rhetoric of romantic medievalism, unaware that the gloom and bigotry of the past is slowly unraveling at the expense of liberal reforms: ‘[Jude] did not at that time see that medievalism was as dead as a fern-leaf in a lump of coal; that other developments were shaping in the world’.

The Jude manuscript shows Hardy continually revised and added textual referents to the haunting sequences, and many names and quotations from ‘legendary’ Oxonians have been added between the lines, in the margins, or asterisked and written on the back of the page. However, a single elision, Mark Pattison, has been made twice during the later haunting scenes in the manuscript: ‘“The phantoms of my fancy.” They used to look friends in the old days, particularly […] Mark Pattison.’ In the same episode, Jude says that he can see spirits ‘‘coming up that lane—Wycliffe—Pattison—Arnold—and a whole crowd of Tractarian Shades’’.

So why is Pattison’s name redacted?

During his time as Rector of Lincoln College, Oxford, Mark Pattison was a scathing critic of the Oxford Movement’s retrogressive influence over university reforms. Pattison had gone as far as to describe the Oxford Movement in his Memoir as ‘hidebound in narrow clerical prejudice […] stagnant with sameness and custom.’

In noting Pattison’s name in the manuscript, Hardy’s critique on university politics takes on a nuanced historical resonance. It shows Hardy contending with the notion that at Oxbridge ‘intellect in Christminster is pushing one way, and religion another […] [and that] medievalism will have to go’.

While the reason behind the redaction of Pattison is subject to speculation, his name might have been removed because Hardy deliberately portrays Jude as tragically unaware of ‘other developments’ shaping the world. Jude’s ‘obscurity’ from privileged information leads him down a blind path, and helps to compound what is an ultimately a misguided tragedy.

The omission of a single name may appear innocuous. However, on closer scrutiny the act of initially adding and subsequently taking away an intertextual referent provides a unique insight to the act of building and refining a work of fiction. The original inclusion of Pattison’s name helps create a careful historical backdrop to a politicised literary space; his redaction exemplifies the way Hardy crafted his characters’ motivations and cultivated an ironic narrative distance.

Research conducted as part of the M.Phil. in English Studies: Modern and Contemporary, Faculty of English, University of Cambridge.

Please cite as: Piers Antony Henriques, The Elision of Mark Pattison in Hardy’s proofs, ‘The Manuscripts Lab’, April 2016.